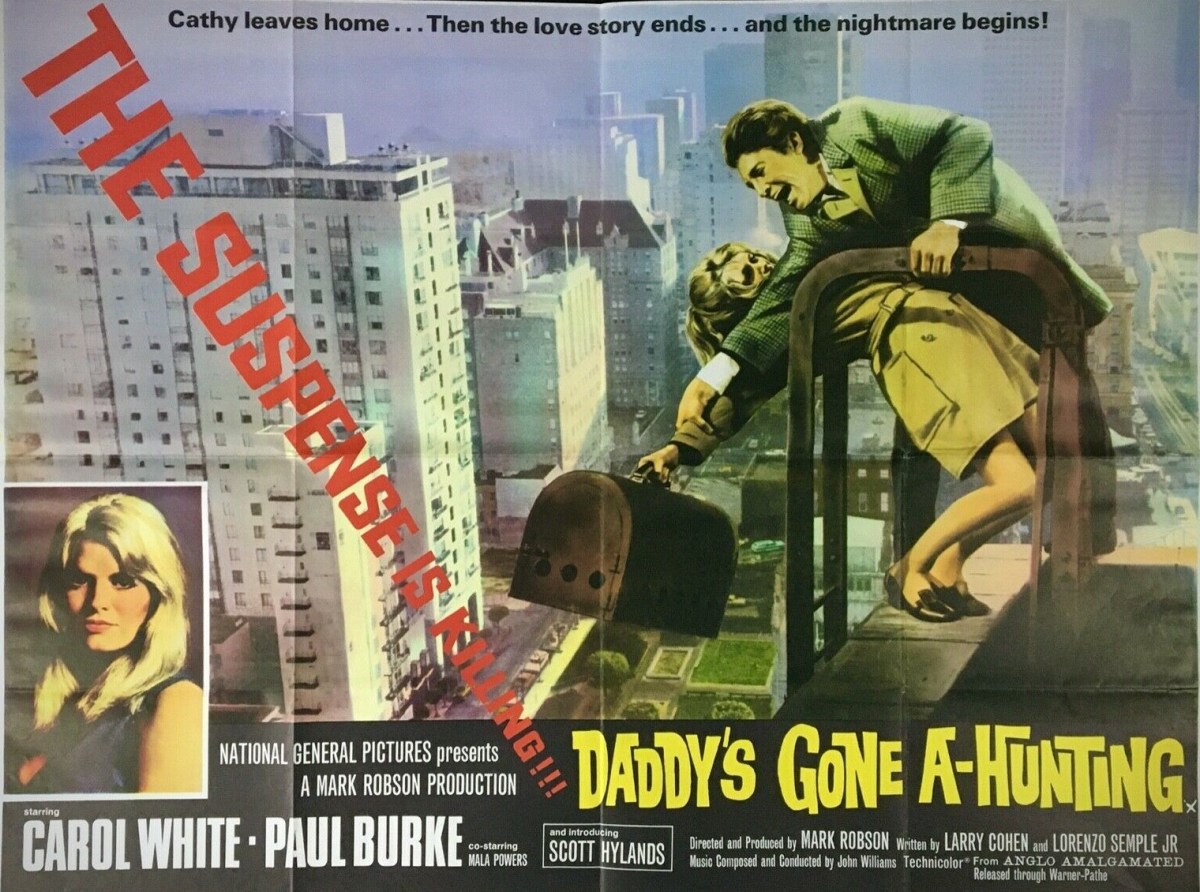

Take all the best elements of the Brian De Palma canon – conflicting perspective, stylish camerawork, complex narrative, diffuse sexuality, a sense of a director on the prowl, what you think you see not actually what is taking place. Take all the worst elements of the Brian De Palma oeuvre – conflicting perspective, stylish camerawork, complex narrative, diffuse sexuality, a sense of a director on the prowl, what you think you see not actually what is taking place. Yep, the very elements that make his movies work are usually what make them not work at all.

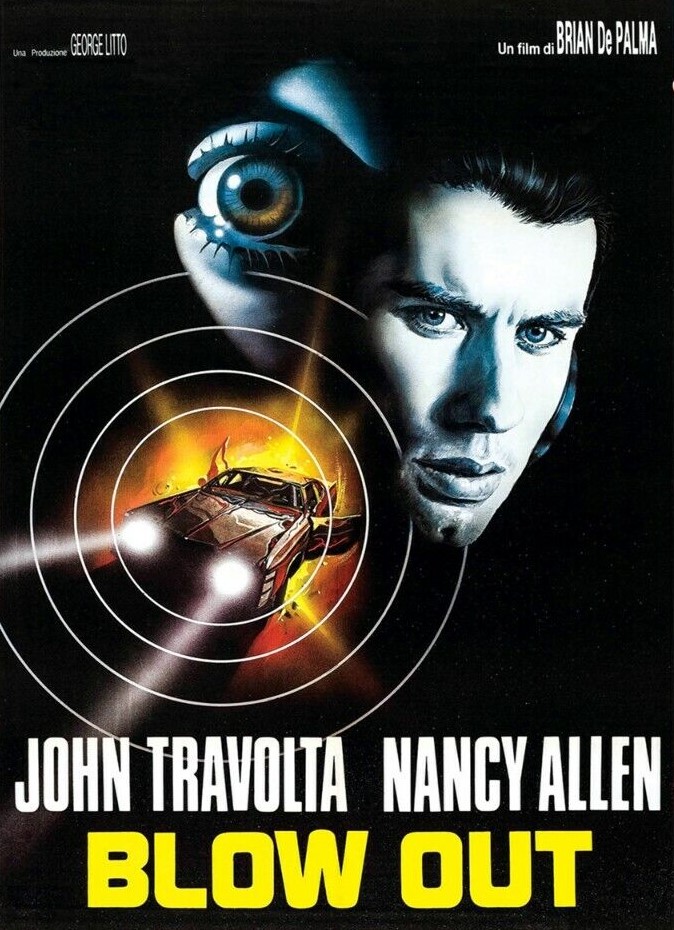

Here, in embryo, is the director of the future – the one whose understanding of cinema, excess, and willingness to take chances delivered such gems as Sisters (1972), Obsession (1976), Carrie (1976), Blow Out (1980), Dressed to Kill (1981), Scarface (1983) and The Untouchables (1987). And such misfires as The Fury (1978), Home Movies (1979), Body Double (1984), Bonfire of the Vanities (1990) and Femme Fatale (2002).

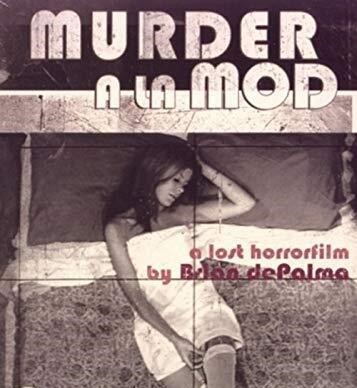

File this under “lost movie,” too self-conscious for arthouse, not enough narrative drive to be commercial, but sufficient experimentation to make it interesting. Setting aside the director’s penchant for showing off, this is as full of twists as many of his later films. As in Dressed to Kill the purported heroine is killed off, as in Body Double the narrative is on the sleazy side, extremely sleazy if you consider the snuff movie section, as in Blow Out we’re not sure who or what to believe, and in homage to Psycho (1960) the good girl turns bad in order to smooth out a relationship with a married man.

Ironically, the opening is an unintended ironic homage to Me Too as an off-camera director tries to get a succession of girls to take off their clothes – and perhaps someone will do a study of just how many starlets were led to the casting couch in this fashion or convinced that nudity was the only way to advance their career. Each of the women have but one line to speak, about only doing this to finance a divorce. For one unfortunate, this is the last screen test she’ll undertake as she is slashed to death.

Karen (Margo Norton) discovers her lover Chris (Jared Martin), who she believed to be a widower, is in fact not only married but a director of sexploitation films and complicit in a peeping tom scam. He is only doing this, he says, to finance a divorce. She is so in love that, apparently in keeping with the times, she accepts being slapped around. And so in love that, to prevent him wasting his talent by demeaning himself on such shoddy goods, she steals cash from socialite pal Tracy (Ann Ankers) to fund the divorce.

After a fake attack by nutcase Otto (William Finley) with a prop ice-pick, Karen is done to death by a real assailant with a real ice-pick. So then the tale shifts into Rashomon territory as we follow the perspective of different characters in different time periods, each time uncovering a bit more of the truth – or perhaps the fiction, who knows.

It’s quite a bold statement of directorial confidence to play bait-and-switch with the narrative, as characters who seemed resolutely in the background lurch into the foreground and at times the camera jiggery-pokery gets in the way of the narrative jiggery-pokery.

But there’s enough going on to maintain audience interest, even if sometimes the novelty of direction seems an indulgence too far. Possibly, from the contemporary viewpoint, this is better viewed as a historical document, a condemnation of the lure of cinema, how the male hierarchy believed that females were so submissive that they could easily be persuaded, with the offer of very little in the way of a concrete career, to disrobe, and almost taking the attitude that should someone object it mattered little because there were plenty others willing to put ambition before principle.

One of the best scenes is a creepy ogling bank manager, the kind of ugly male who assumes that from his position of authority he is superior to a woman who is way out of his league and far wealthier than he’ll ever be. Though why she is dumb enough to leave her valuables in an unlocked car is anybody’s guess, except for narrative convenience and the opportunity to rack up some Hitchcockian tension when a cop suddenly appears and begins to interrogate the woman the audience knows is a thief.

There’s a DVD around somewhere plugging this as the “lost” De Palma movie, but you can catch it for nothing and judge just how indicative of De Palma’s talent it might be – and how much he was served later by hiring better actors – on Youtube.