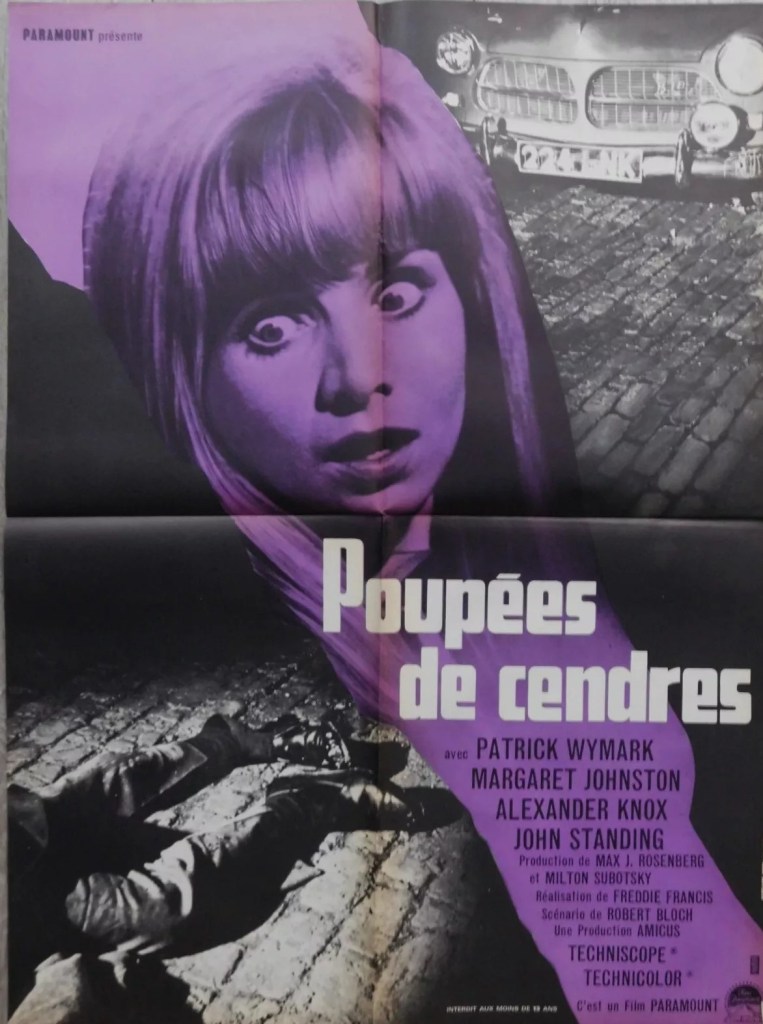

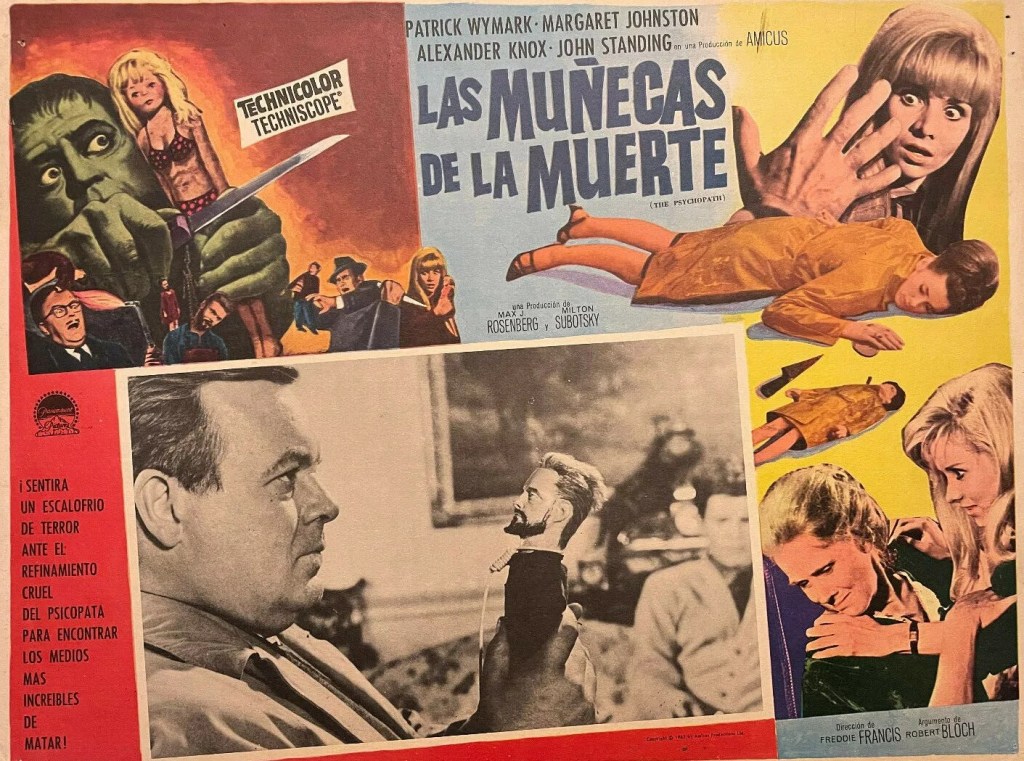

Amicus was part of an unholy triumvirate – the others being Hammer and American International – serving up horror during the 1960s to a global audience. Less prolific than the others, Amicus, headed up by expatriate New Yorkers Milton Subotsky and Max Rosenberg, had an American distribution deal with Paramount.

However, the pair had been more successful, at least in Britain, on the sci fi front, Dr Who and the Daleks (1965), an adaptation of the highly successful BBC television series, had been a huge hit on the domestic front, with the sequel Daleks Invasion Earth 2150AD (1966) not too far behind. But both had landed like a damp squid in the U.S.

Nor had their previous incursion into the horror fields done much better. Dr Terror’s House of Horrors (1965) had only managed a release as a supporting feature in Britain. The same fate was accorded The Skull (1965), but only after sitting on the shelf for a year. So a great deal was riding on their third horror picture. The whopping success of Dr Who and the Daleks, at least in Britain, guaranteed them a stay of execution.

“I like making horror films,” said Subotsky, “or perhaps I should say films of imagination rather than reality. The second thing is I like silent pictures. I think you should be able to tell a story visually and not by talking. And in horror films you can have long stretches of action.”

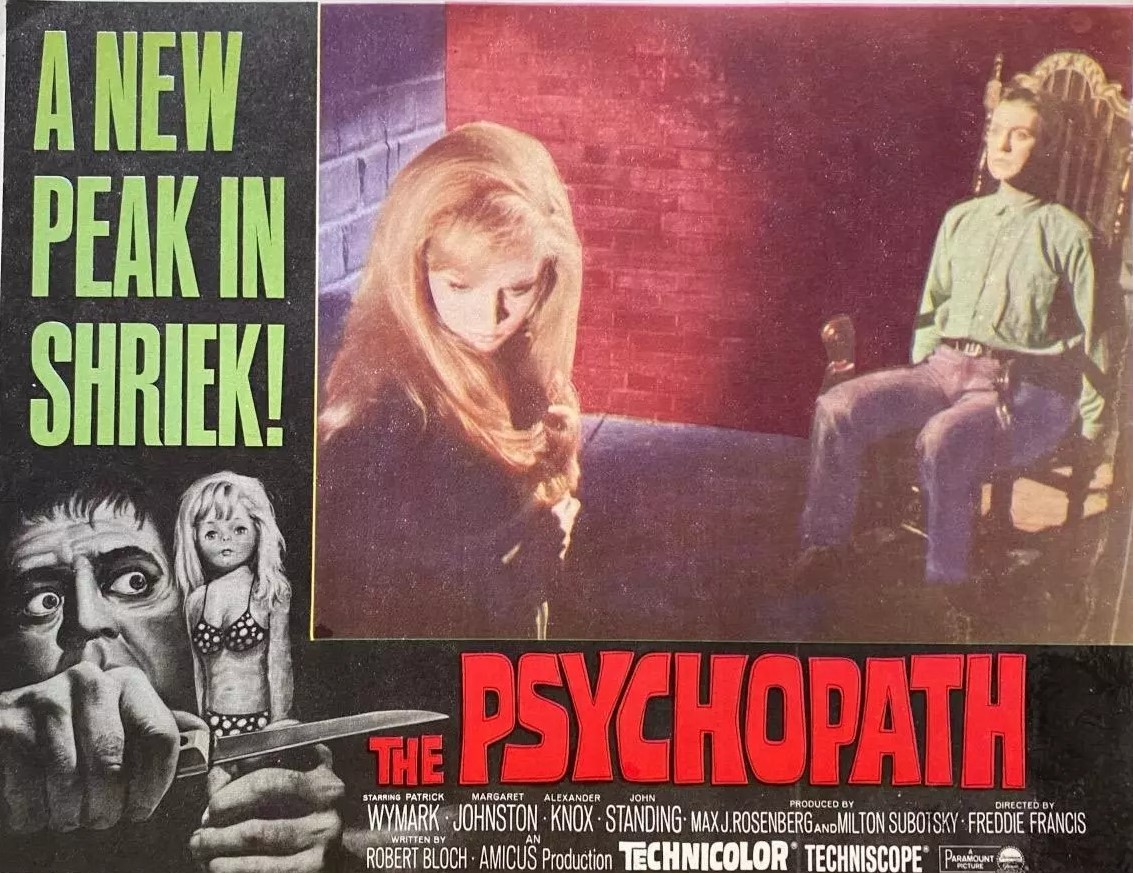

The Psychopath – initially going before the cameras as Schizo – looked a promising venture. The biggest name attached was quite a catch, even if not one who would feature in the picture. Robert Bloch, courtesy of Pyscho (1960), filmed to enormous critical and commercial acclaim by Alfred Hitchcock, was the most famous name in horror. He had penned the story that became The Skull. In addition to buying the rights to his story, this time Amicus lined him up for screenwriting duties.

In front of the camera, Amicus gambled on Patrick Wymark, a big British television star courtesy of The Plane Makers (1963-1965) who was elevated to top billing after playing the second lead in The Skull. Direction was once again by Freddie Francis, who had won the Oscar for cinematography for Sons and Lovers (1960). Francis specialized in horror – helming The Brain (1962), Paranoiac (1963), Nightmare (1964) and The Evil of Frankenstein (1965) before becoming Amicus’s in-house director with Dr Terror’s House of Horrors (1965) – the first of the portmanteau features with which Amicus would later be associated – and The Skull.

He was credited with a distinct individual visual style – attracting the attention of Cahiers du Cinema and French critics – and was considered a safe pair of hands. However, that last element was tested here. Halfway through shooting it was obvious the movie was going to come up short in terms of running time. It was already intended to be a tight little feature, at a projected 80 minutes. It was apparent that without substantial changes the movie would come in ten minutes shy of the planned time. Even at 80 minutes, it would struggle to qualify for main feature status. At 70 minutes, it would have no chance.

The producers did not always see eye-to-eye. Although Milton Subotsky had been responsible for setting up the project, Rosenberg soon took over. Complained Subotsky, “I found Max could really be a bully when he wanted and he had nasty temper. I’ll admit I was never good at standing up for myself and he just walked all over me.”

However, when the movie hit the running time stumbling block, Rosenberg had to turn to his colleague for help. Subotsky had written Dr Terror’s House of Horrors, Dr Who and the Daleks and The Skull. Taking a utilitarian approach, Subotsky availed himself of whoever was on set or available.

The burden fell on Robert Crewdon who played the sculptor Victor. Subotsky added his murder scene which was shot in a scrapyard created on the back lot at Shepperton with a batch of old cars purchased for £300. Subotsky apparently also directed the scene since Freddie Francis was busy elsewhere.

However, the running time wasn’t the only problem. Once the picture was complete, it was fairly obvious who the killer was. So Subotsky took over the task of re-editing the movie as well. “Apart from wanting to be a writer, (Milton) wanted to be an editor,” explained Freddie Francis.

Subotsky rearranged the picture so that “every time Patrick Wymark opens his mouth, we cut away from him, and overlaid his dialog, and every time someone replied we overlaid their dialog. And we changed the whole last scene with post-synched dialog and that way we changed the murderer.”

Though reviews were generally positive – “atmospheric thriller” (Box Office), “top grade shocker” (Variety), the backers were not happy with the result, even the extended version. The extra 13 minutes of footage wasn’t sufficient to win a main release of the British ABC circuit – it went out as support and later was reissued with The Skull. In the U.S. it had a varied, though hardly wide, release. In some cities, Paramount sent it out as support to The Naked Prey. In first run in St Louis, Cincinnati, Boston and Portland, it was the main feature with supports including reissues of Nevada Smith (1966) and Lady in a Cage (1964) Box office was generally “tepid,” “mild” or “dull”. It supported A Study in Terror (1965) in Kansas City and Chamber of Horrors (1966) in Toronto. It didn’t make much money in either country, but did very well in Italy.

Robert Bloch wasn’t pleased either. “The idea is better than the film,” he complained. “It would have made a better one-hour teleplay than a feature.”

This was the third in Amicus’s four-picture deal with Paramount and after The Deadly Bees (1967), the Hollywood studio severed contact.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of this company best known for its horror output is that for a considerable period it tried to shuck off that tag. To some extent, it became a horror specialist by default because other projects failed to get off the ground – for example in 1964 it was scheduled to make How I Won the War with Richard Lester for United Artists and Adventure Island based on an Arthur C Clarke tale for Universal – or because a switch into other genres failed to hit the box office mark.

After the dual flop of The Deadly Bees (1967) and Torture Garden (1967), the duo lined up spy thriller Danger Route (1969) and literary drama A Touch of Love/Thank You Very Much (1969) with Oscar winner Sandy Dennis. They should have been followed by adaptations of Ancient Pond by Courtney Brown – described as “a novel of passion and revenge in a war-ravaged city” – and sci fi satire The Richest Corpse in Showbusiness by Dan Morgan, both novels purchased in 1967. But neither was greenlit and eventually Amicus returned to what it did best – horror.