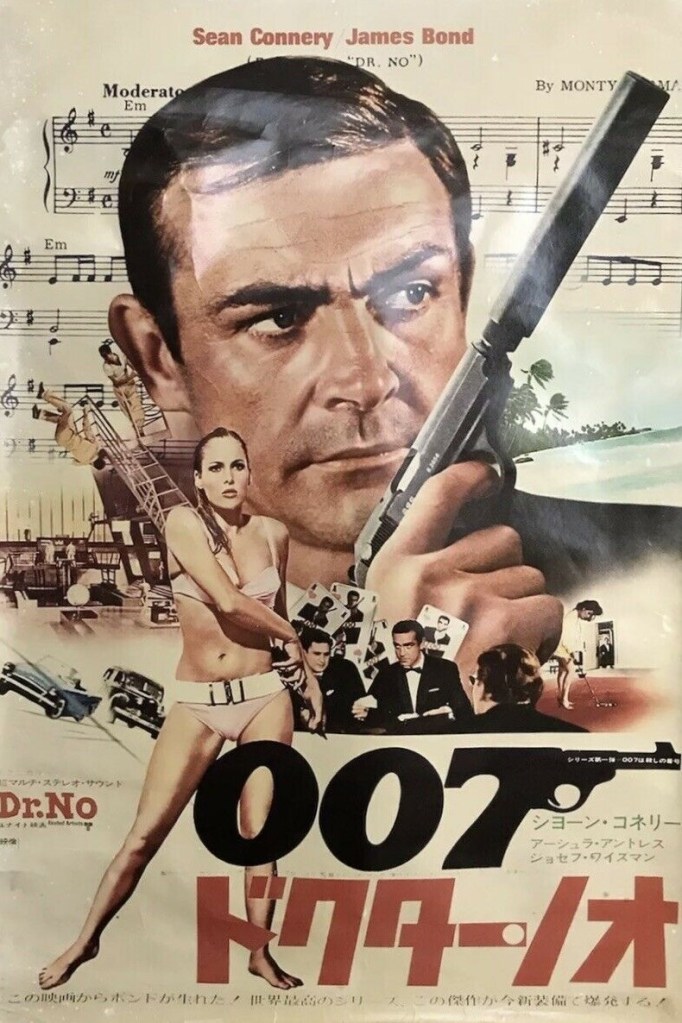

Dr No (1962) was more famous for kick-starting nascent careers – step forward Sean Connery and Ursula Andress – rather than reviving careers that had looked dead and buried as was the case with Zena Marshall. I had just come across Ms Marshall in her last picture, The Terrornauts (1967), a cult sci fi from Amicus, that I had been asked to provide an audio commentary for (you’ll have to wait till next year for that) and was intrigued to discover that, while never becoming a big star, she had managed to eke out a decent living since her debut in Caesar and Cleopatra in 1945. She’d never achieved much more than rising star status, B-movies more her line. She hadn’t made a picture in five years until Dr No but thereafter managed leading lady once a year until her retirement.

Director Peter Maxwell (Serena, 1962) fell into much the same movie backwater but still had the knack of generating interesting narratives. The screenplay turns on some interesting realism, an unusual gadget (especially for this genre) as well as a couple of entertaining happenstances and in Zena Marshall one of two very self-assured females who light up a picture otherwise peppered with dour males.

Extant posters of “The Switch” are non-existent, it appears.

A joint police and customs operation has snared a smuggler in a sting. But, almost immediately after Inspector Tomlinson (Dermot Walsh) and Customs Agent Bill Craddock (Anthony Steel) latch onto their prey, their informant ends up in the River Thames and they hit a dead end trying to find the Mr Big behind the high-class watch smuggling racket.

Meanwhile model Carolyn (Zena Marshall), on holiday in France, is taken for a romantic meal by seductive Frenchman Lecraze (Arnold Diamond) while his colleagues stuff her petrol tank with watches.

Takes a while for Carolyn to become a suspect. There’s quite a lot of fun to be had from unexpectedly inept gangsters. When she returns home, she finds her flatmate’s cousin John Curry (Conrad Phillips) having a bath. With his car parked in her garage, she finds somewhere else to stay. His car is mistakenly stolen, as is the car she exchanges at the garage while the original one she brought back from France is in for repairs. The crooks repeatedly steal the wrong car.

Eventually, the cops break open her petrol tank and find the hidden watches. Although under suspicion she is freed, and, being a confident young lass, and quite accustomed to men of all ages taking her out for dinner and buying her presents, is nonetheless surprised when her latest admirer John presents her with his firm’s latest invention, a miniature radio transmitter hidden inside a cigarette case.

Which is just as well because the Frenchman reappears and kidnaps Carolyn hoping to find out from her what happened to her car. Meanwhile, the cops dig up gangster’s moll Janice (Dawn Beret) whose boyfriend is mixed up in the villainy and has herself unwittingly brought stolen goods into the country in her petrol tank after being chatted up by a smooth Frenchman. She’s a cheeky young thing, as self-assured as Carolyn, suggesting to the straight-laced inspector that if he’s not doing anything at the weekend they could get married.

Meanwhile, John has teamed up with the good guys while they manage to survive Janice’s stream of quips and attempt to track down the kidnapped Carolyn. She doesn’t manage to hold out for long, not when Mr Big removes the gloves.

All in all, it’s cleverly done, playing all the time with audience expectation, not just the cocky confidence of the two women, who are clearly accomplished at leading men astray, but the quirks of the storyline – including a failed escape up a chimney – the details of the smuggling operation, and the introduction of the James Bond-style gadget. There’s even some cheeky self-awareness, John seen sitting up in bed reading the movie tie-in edition of Dr No which features Zena Marshall on the cover.

Apart from Zena Marshall, there’s an interesting cast. Anthony Steel (The Story of O, 1975), husband of Anita Ekberg, was just back from a stint in Rome. Conrad Phillips (The Secret Partner, 1961) had played William Tell in the television series and Dermot Walsh Richard the Lionheart in similar. It marked the last screen appearance of Susan Shaw (Fire Maidens from Outer Space, 1956) and perky Dawn Beret (Victim, 1961) looked promising. In bit parts look out for Carry On regular Peter Butterworth and Rose Alba (Thunderball, 1965)

This sat on the shelf for a year before going out on the Odeon circuit as support to spy picture Hot Enough for June/Agent 8¾ (1964) starring Dirk Bogarde.

Except for horror, Britain didn’t stoop to having B-Movie Queens, but if they had Zena Marshall would wear the crown.