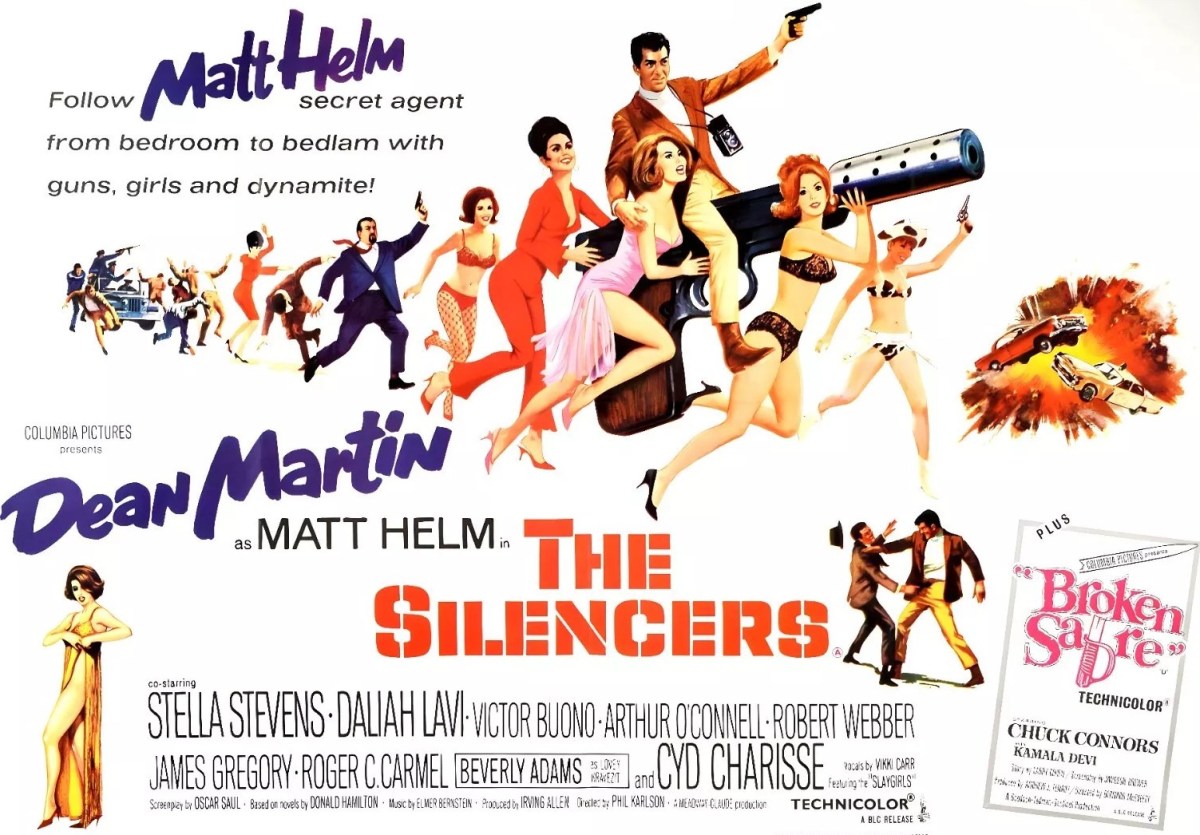

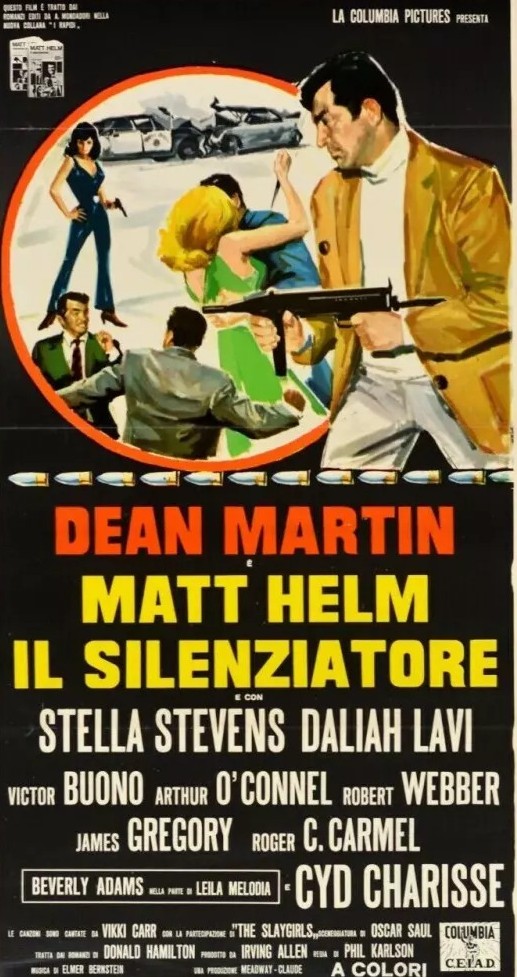

An absolute delight. Have to confess though I had been pretty sniffy about even deigning to watch what I always had been led to believe was an ill-judged spoof of the Bond phenomenon especially with a middle-aged Dean Martin with scarcely a muscle to crease his stylish attire.

Full of witty repartee, and even a whole jukebox of snippets from the Dean Martin repertoire (plus an aural joke at the expense of Frank Sinatra) and a daft take on the Bond gadget paraphernalia. The spoofometer doesn’t go anywhere near 10 and the whole enterprise not only works but damn near sizzles. No wonder it led to another three.

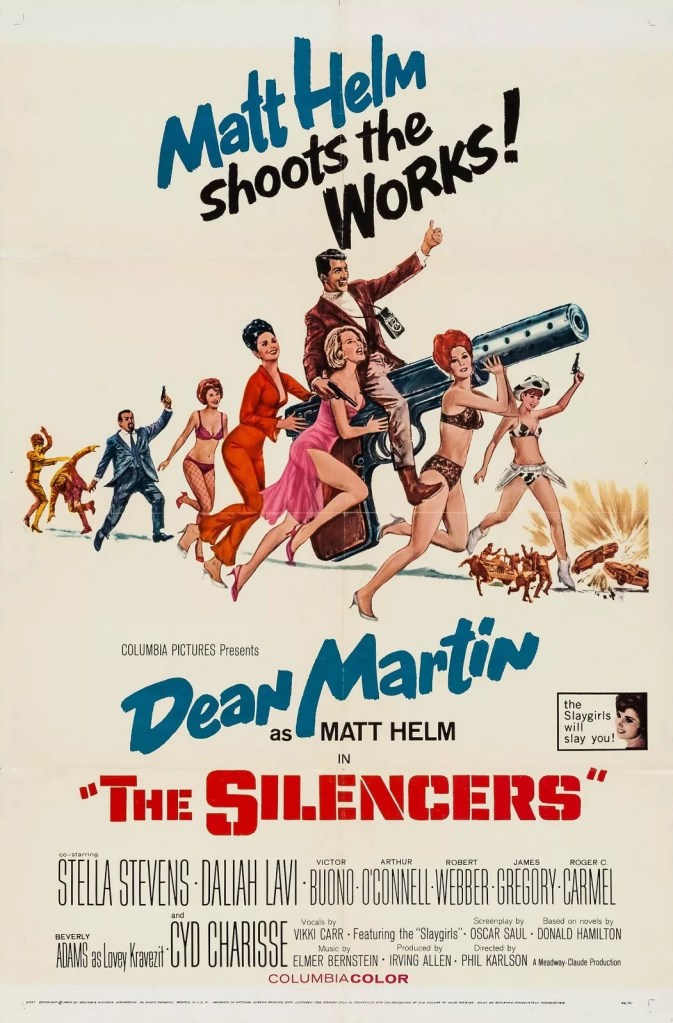

Called out of retirement – hence cleverly swatting away any jibes about his age – Matt Helm (Dean Martin) resists becoming re-involved in the espionage malarkey until his life is saved by former colleague Tina (Daliah Lavi) as he falls for the seductive technique of an enemy agent. Back in harness with ICE (Intelligence and Counter Espionage), Helm is called upon a thwart a dastardly scheme by the Big O organization headed by Tung-Tze (Victor Buono) to stage a nuclear explosion.

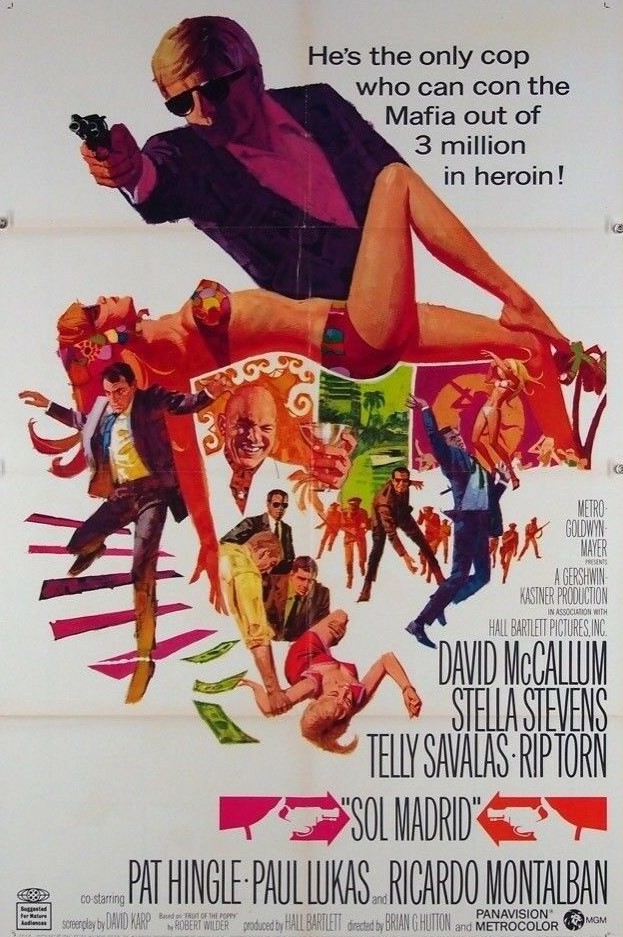

Some malarkey about a secret computer brings into Helm’s sphere the klutzy Gail (Stella Stevens) whom he initially treats with suspicion. Gail and Tina end up as rivals for Helm’s afections.

But you could have invented any number of stories and they would still have worked because it’s the rest of narrative that makes the whole thing zing. We could start with the massive effort that goes into ensuring that the private parts of naked men (and women) are concealed by a wide variety of objects, a kind of bait-and-switch that paid homage to the James Bond legend while casually taking it apart. Since Helm now operates legitimately as a fashion photographer it makes sense that his most deadly gadget is a camera that fires miniature knives.

And knowing how much delight villains take in despatching secret service agents in the most gleeful fashion, wouldn’t it make sense to kill said agent with his own gun? Who could resist such a notion? Until it, literally, backfires and the bad guy is shot by a gun that shoots a reversible bullet – two bullets if you’re so dumb you can’t believe that’s what’s happening and you shoot yourself twice.

And what about the laser? Another famed Bond device. Why not have that go haywire?

But there’s also a playful Heath Robinson aspect to those gadgets whose purpose is pure labor-saving. Helm can automate his circular bed so he doesn’t have to get out of it to answer the phone and to save him walking a few steps into the bath the bed is programmed to jerk upwards and tip him in.

“Treasure hunt,” remarks Helm, slyly, as he spies a string of discarded female clothing. But making love to a strange woman feels rude so Helm is impelled to complain they haven’t been introduced. “You’re Matt Helm,” says the stranger. “Good enough,” replies Helm.

And that’s before we come to the joy of Gail, who has been taking lessons from Mrs Malaprop, and, despite lurching into Helm at every opportunity, giving him the mistaken impression that she’s keen to get to know him better, Gail actually is wary. So wary that in a thunderstorm she tries to escape their cosy nest of a car (equipped with separate sleeping arrangements, don’t you know) only to end up slipping and sliding through the mud.

While Daliah Lavi (The Demon, 1963) isn’t exactly called upon to act her socks off, she at least is afforded a believable character, but she can’t hold candle to Stella Stevens (Rage, 1966) when the blonde one decides to go full-tilt boogie into comedy slapstick. Sure, Stevens relies overly on other occasions on a pop-eyed look, but the thunderstorm sequence reveals a deft, and willing, knack for physical comedy.

Dean Martin (Rough Night in Jericho, 1967) struck a solid seam with his interpretation of Helm, slick enough to get away with Bond-style lothario, laid-back enough for no one to take it seriously.

Nancy Kovack (Tarzan and the Valley of Gold, 1967), Cyd Charisse (Maroc 7, 1967) and Beverley Adams (Hammerhead, 1968) up the glamor quotient.

Director Phil Karlson (The Secret Ways, 1961) and screenwriter Oscar Saul (Major Dundee, 1965), adapting the Donald Hamilton bestseller, provide the basic template but Dean Martin makes it work.

Great fun.