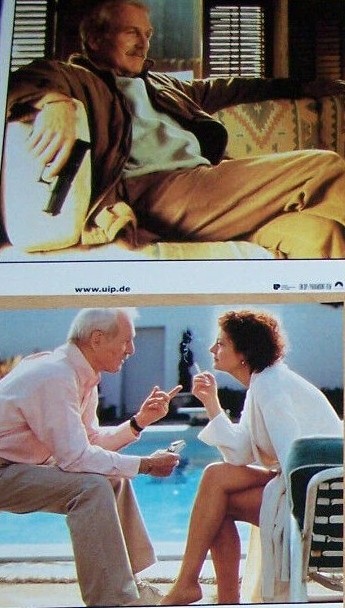

This has been lost for decades – and with good reason. Even Katharine Hepburn fresh from an Oscar-winning turn in The Lion in Winter (1968) can’t save this and to be honest I’m struggling to see why anyone wanted to make it in the first place beyond newcomer Commonwealth United intent on making a splash. That it made nothing of the kind is down to a variety of reasons.

First of all, it’s clearly intended as some kind of broad satire on financiers and the kind of get-rich-quick schemes that prey on the ill-informed. Secondly, you might as well have called it Eccentrics Assemble from the number of oddballs present. Thirdly, director Bryan Forbes (King Rat, 1965) works on the principle that he doesn’t need to explain anything – least of all provide important characters with actual names – because it would all be obvious to an intelligent audience. Lastly, and possibly most important of all, since it doesn’t fit into any obvious genre it just jumps between a bunch of them, including the Absurd.

In fact, some of the better sections are driven by absurd situation or observation. Countess Aurelia – the titular madwoman – points out that the Futures market consists of buying something that doesn’t exist and selling it when it does. A policeman tries to save a man who hasn’t drowned by applying the techniques used to save a person who has drowned. You get the gist? I didn’t.

The basic story concerns a bunch of millionaires attempting to acquire the mineral rights to the land underneath Paris because The Prospector (Donald Pleasance) has discovered oil. Did he drill for it? Did tar deposits rise to the surface? Nope, he has detected the existence of oil by sampling water that has been sourced from the ground.

He involves a bunch of Disparate Anonymites, all designated by occupation or title, thus The Chairman (Yul Brynner), The Reverend (John Gavin), The General (Paul Henreid), The Commissar (Oskar Homolka) and The Broker (Charles Boyer) who spend most of the time sitting outside a café complaining.

The Broker is something of an oddity, being both entrepreneur and revolutionary, all set to direct his nephew Roderick (Richard Chamberlain) to explode a bomb in Paris. Naturally, when this plan fails what else is there for Roderick to do but fall instantly in love with waitress Irene (Nanette Newman).

If this isn’t barmy enough for you, Aurelia is stuck in the past, rereading a newspaper from decades ago, while one of her friends Constance has an invisible dog and another Gabrielle an invisible lover. You can see where this is going. If so, you’re doing better than me.

Aurelia, who gets wind of the scheme from Roderick and The Ragpicker (Danny Kaye), decides to exterminate the financiers by luring them into her cellar. Why she didn’t prevail on Roderick to provide her with another bomb to blow them up is anybody’s guess.

Anyway, before she can do the necessary luring, she conducts a mock trial, finding the financiers guilty of everything that anybody with a scintilla of sense would be fully aware of and hardly need such a heavy-handed lecture.

Everyone comes out of this with egg on their face. The only reason it doesn’t get no stars at all is that anything has to be better than Orgy for the Dead (1965) and Anora (2023) and the only reason it isn’t given the one-star rating of that picture is because Katharine Hepburn is in the cast and even though, as I said, she can’t save it, but I wouldn’t to put her in the same category as the nudie horror.

Bryan Forbes and Oscar-winning screenwriter Edward Anhalt (Becket, 1964) expanded the original play by Jean Giraudoux.

YouTube, where this is showing, clearly believed nobody would get to the end of it because it’s absolutely riddled with adverts, literally one every couple of minutes.