Doomed for half a century to be seen as Saturday television matinee material and then put into the shade by the Zack Snyder’s stylish 300 (2006), The 300 Spartans is in sore need of re-evaluation. Lacking the big budget of an El Cid (1961) or Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and released during an era when historical drama – Barabbas (1961), The Mongols (1961), Sword of the Conqueror (1961), The Trojan Horse (1961), and The Tartars (1961) – was at a peak, this is a stripped-down version of the famous Battle of Thermopylae in 480 B.C. and none the worse for it.

Clever camerawork suggests thousands of warriors involved but there is little sign of scrimping in the wardrobe department and there is more than enough action. Also, this is a surprising literate picture, with great lines for cynical politicians as much as for warriors and peasants. Themistocles (Ralph Richardson) comments: “Some day, I may enter religion myself. It’s better than politics. With the gods behind you, you can be more irresponsible.” Told that the invading Persian army has “arrows that will blot out the sun,” Spartan King Leonides retorts, “then we will fight in the shade.” And there’s sexist banter typical of the period between a peasant couple: wife – “goats have more brains than men”; husband – “who can understand the ways of the gods, they create lovely girls and then turn them into wives.”

Quite how Leonides ends up fighting the massive army on its own is down to a mixture of politics and religion. Oracles foretell doom. The various Greek states refuse to join together, although Athens lends Sparta its fleet (“Athens’ wooden wall”). Even Sparta officially refuses to participate on the grounds that battle would interrupt a major religious festival. Leonides’ “army” of 300 men is comprised of his bodyguard. A romantic subplot involving a young couple results in catastrophe. Just how ruthless is the opposition is shown when Persian king Xerxes slaughters all his soldiers’ wives to make the men more determined to get to Greece where doubtless they will enslave the female population. When his archers fire, he doesn’t care if the arrows hit his own men.

What marks out the best historical action pictures is the intelligence behind the battle. Strategy is key. The first weapon, of course, is surprise so the Spartans sneak into the Persian camp from the sea and burn their tents. During battle, to counteract the Persian cavalry, the front row of the Spartan army lies down and allows the horses to jump over them, then rising up, traps the cavalry and drives them into the sea. Other clever measures are used deal with the Persian crack infantry regiment, the Immortals. Even at the end, the Spartans continue to confound the enemy with clever ruses.

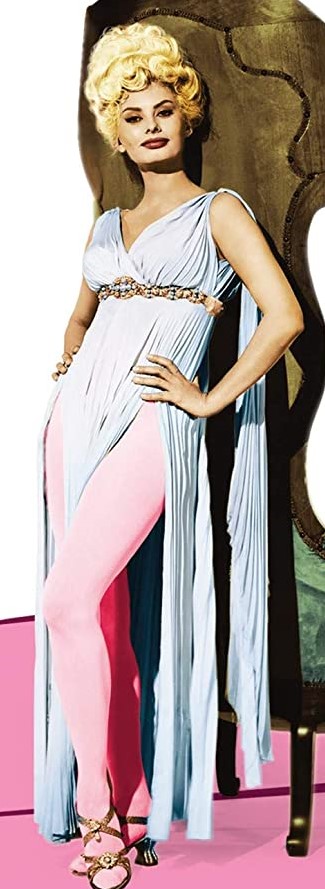

Richard Egan is effective as Leonides, Ralph Richardson excellent as the wily but honourable Themistocles while Hitchcock protégé Diane Baker (“glaringly miscast” according to Variety) has the female lead though Anne Wakefield as a Persian queen the more interesting role. Former British star David Farrar (Meet Sexton Blake, 1945) is the intemperate Xerxes.

Five-time Oscar-nominated cinematographer Rudolf Mate delivers the directorial goods, his handling of the dramatic scenes as confident as the action and masking the holes in his budget by making clever use of trees as the invaders march, suggesting an army far bigger than he could afford to put on the screen. Color-coding the Spartans – they were in red – made the action clearer to follow. George St George, with few credits of notes (and few at all) doubling up as producer, wrote the script. This thoughtful drama with striking action deserves reassessment.