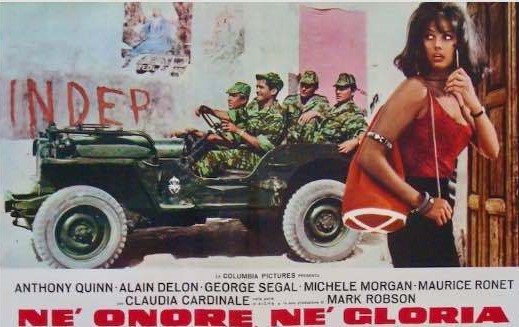

Derring-do and heroism were the 1960s war movie default with enemies clearly signposted in black-and-white. This one doesn’t fall into that category, in fact doesn’t fall into any category, being more concerned with the military and political machinations pervasive on both sides in war. Movies about revolutions generally succeed if they are filmed from the perspective of the insurrectionists. When they take the side of the oppressor, almost automatically they lose the sympathy vote, The Green Berets (1968) in this decade being a typical example, although the sheer directorial skill of Francis Coppola turned that notion on its head with Apocalypse Now (1979) when slaughter was accompanied by majesty. In the 1950s-1960s the French had come off worse in two uprisings, Vietnam and Algiers. This movie covers the tale end of the former and the middle of the latter and it’s a curious hybrid, part Dirty Dozen, part John Wayne, part dirty tricks on either side, with a few ounces of romance thrown in.

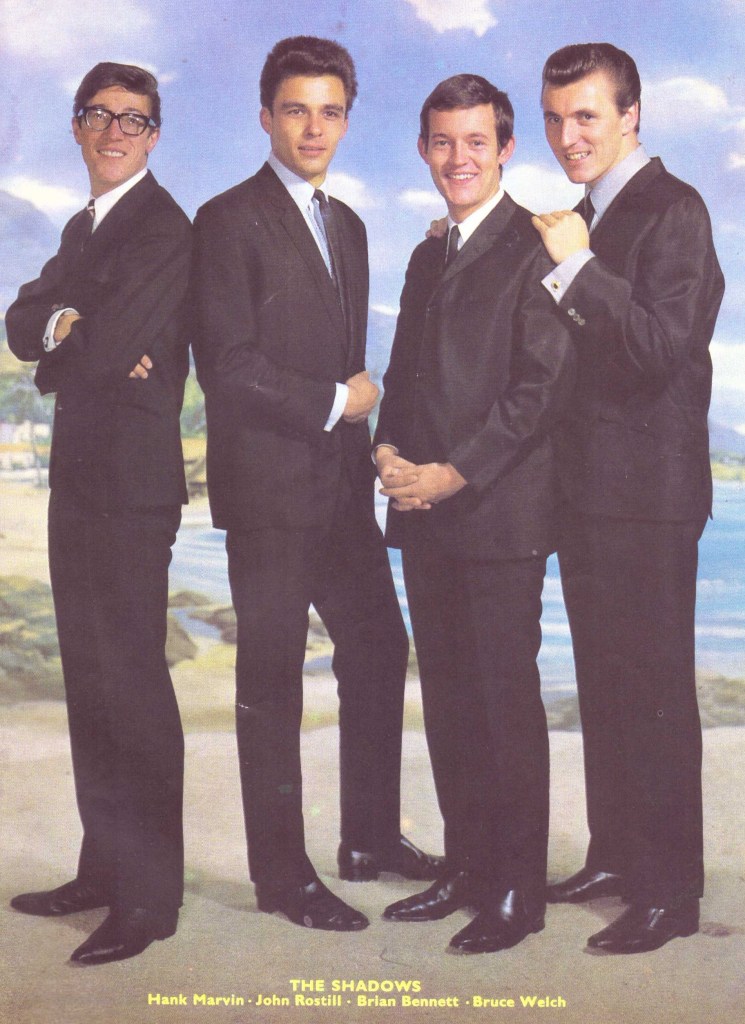

Anthony Quinn, in unlikely athletic mode (that’s him leaping in the poster) is the officer of a paratroop regiment who sees out the debacle of the final battle of the French war in Vietnam, loses his commission, and then, reprieved, is posted to Algeria, where the fight for independence is in full swing, with a ragbag of rejects plus some faithful comrades from his previous command. In any spare moment, Quinn can be seen keeping fit, doing handstands, swinging his arms, puffing out his chest, and a fair bit of running, presumably to avoid the contention that he was too old for this part. Alain Delon, a bit too moralistic for the dangerous business of war, plays his sidekick. Quinn is an ideal anti-hero for a hero, an officer who ignores, challenges or just plain overrides authority, adored by his men, hated by the enemy, ruthless when it matters.

The brutal realism, which sometimes makes you quail, is nonetheless the best thing about the picture, no holds barred here when it comes to portraying the ugly side of conflict. The training in The Dirty Dozen is a doddle compared to here, soldiers who don’t move fast enough are actually shot, rather than just threatened with live ammunition, and there’s no second chance for the incompetent – at the passing out ceremony several are summarily dismissed. The only kind of Dirty Dozen-type humor is a soldier who fills his canteen with wine. Otherwise, this is a full-on war. Battles are fought guerilla style, the enemy as smart as the Vietnamese, catching out the French in ambushes, using infiltrators sympathetic to the cause and terrorism. Unlike Apocalypse Now where the infantry appeared as dumb as they come, relying on strength in numbers and superior weaponry, Lost Command at least has an officer who understands strategy and most of what ensues involves clever thinking. The battles, played out in the mountains, usually see the French having to escape tricky situations rather than blasting through the enemy like cavalry, although having sneakily pinched a mayor’s helicopter (though minus Wagnerian overtones) gives Quinn’s team the opportunity to strafe the enemy on the rare occasions when they can actually be found, their camouflage professionally done.

George Segal, unrecognizable under a slab of make-up apart from his flashing white teeth, plays the Arab rebel chief. In terms of tactics and brutality, they are evenly matched, Segal shooting one of his own men for disobeying orders. Claudia Cardinale appears briefly at the start as Segal’s sister and when she turns up halfway through giving Delon the come-on it’s a bit too obvious where this plotline is going. With both sides determined to win at all costs, atrocities are merely viewed as collateral damage, so in that respect it’s an unflinching take on war. The picture could have done with another 15 minutes or so to allow characters to breathe and develop some of the supporting cast. The movie did well in France but sank in the States where my guess is few of the audience would even know where Algeria was. Gilles Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers, out the same year, gave the revolutionaries the leading role. For the most part Quinn is in bull-in-a-china-shop form but his character is more rounded in a romantic interlude with a countess (Michele Morgan), his ability to outsmart his superior officers, his camaraderie with his own soldiers and, perhaps more surprisingly, the ongoing exercise routines which reveal, rather than a keep-fit fanatic, an ageing soldier worried about running out of steam.