It’s five years now since I started this Blog. This little exercise that I generally undertake twice a year reflects the films viewed most often since the Blog began in June 2020. There’s no shaking Ann-Margret, a brace of her movies embedded in the top three, though the sequence has been punctured by the sudden arrival of Anora (2024) and followed by Pamela Anderson as The Last Showgirl (2024), both films making the highest ranking of any contemporary films I’ve reviewed, though I hated the former and adored the latter.

The figures in brackets represent the positions in December 2024 and New Entry is self-explanatory. I’ve expanded the list from 40 movies to 50, which still represents a small fraction of the 1600 pictures I’ve reviewed since I started.

- (1) The Swinger (1966). Despite shaking her booty as only she knows how, Ann-Margret brings a sprinkling of innocence to this sex comedy..

- (New Entry) Anora (2024). Mikey Madison’s sex worker woos a Russian in Oscar-winner.

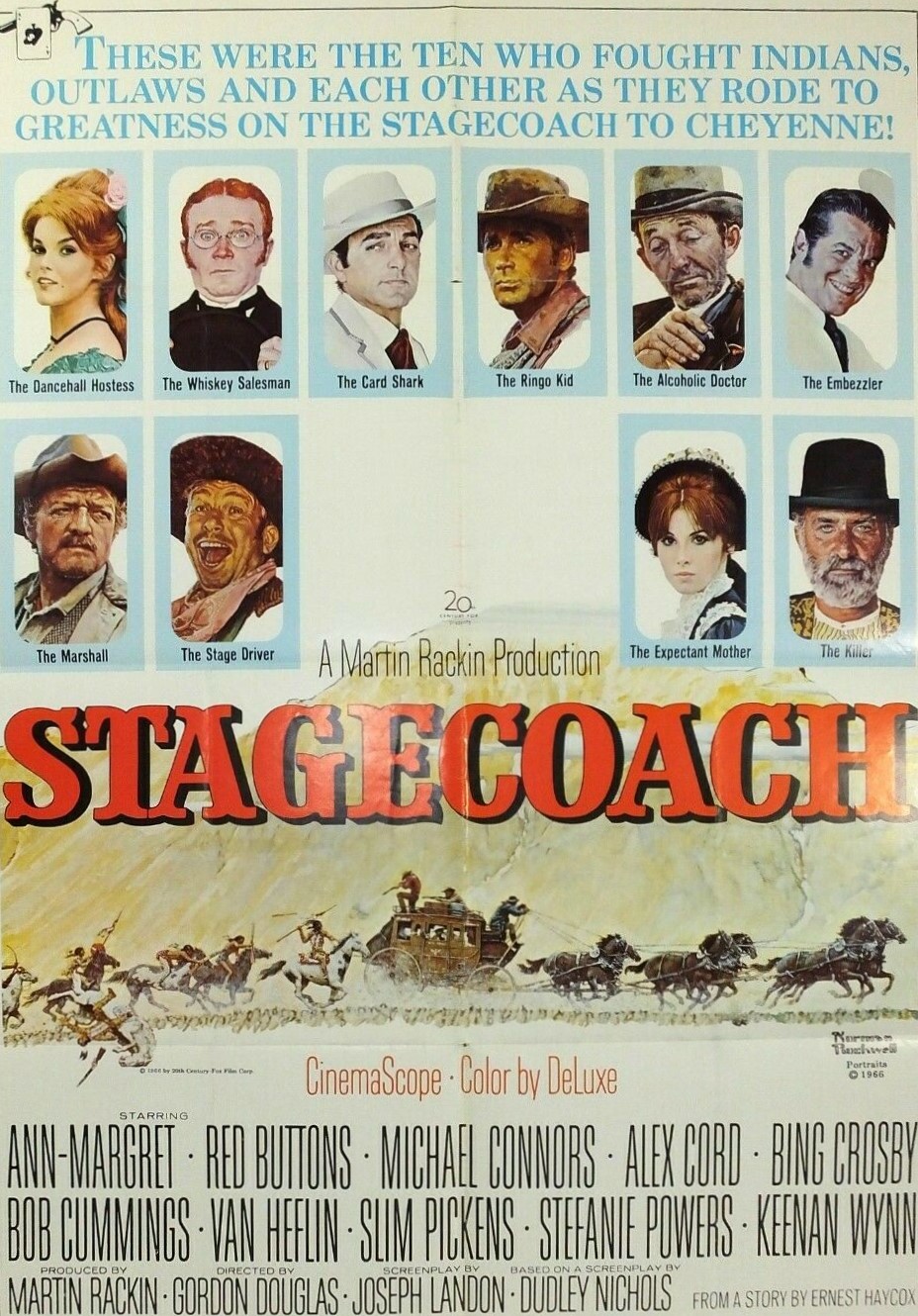

- (2) Stagecoach (1966). Under-rated remake of the John Ford western. But it’s Ann-Margret who steals the show ahead of Alex Cord in the role that brought John Wayne stardom.

- (New Entry)) The Last Showgirl (2024). Pamela Anderson proves she can act and how in this touching portrayal of a fading Las Vegas dancer.

- (4) In Harm’s Way (1965). Under-rated John Wayne World War Two number. Co-starring Kirk Douglas, Patricia Neal, Tom Tryon and Paula Prentiss, director Otto Preminger surveys Pearl Harbor and after.

- (3) Fraulein Doktor (1969). Grisly realistic battle scenes and a superb score from Ennio Morricone help this Suzy Kendall vehicle as a World War One German spy going head-to-head with Brit Kenneth More and taking time out for romantic dalliance with Capucine.

- (5) Fireball XL5. The famous British television series (1962-1963) from Gerry and Sylvia Anderson, now colorized. “My heart will be a fireball…”

- (6) Once Upon a Time in the West (1969). Along with The Searchers (1956) now considered the most influential western of all time. Sergio Leone rounds up Claudia Cardinale, Henry Fonda and Charles Bronson and that fabulous Morricone score.

- (New Entry) Squad 36 / Bastion 36 (2025). Corruption and interdepartmental rivalry fuel this French flic directed by Olivier Marchal.

- (7) Jessica (1962). Angie Dickinson doesn’t mean to cause trouble but as a young widow arriving in a small Italian town she causes friction, so much so the local wives go on a sex strike..

- (20) Young Cassidy (1965). Julie Christie came out of this best, winning her role in Doctor Zhivago as a result. Rod Taylor as Irish playwright Sean O’Casey.

- (8) Thank You Very Much/ A Touch of Love (1969). Sandy Dennis dazzles as an academic single mother in London impregnated by Ian McKellen.

- (10) Baby Love (1969). Controversy was the initial selling point but now it’s morphed into a morality tale as orphaned Linda Hayden tries to fit into an upper-class London household.

- (30) The Girl on a Motorcycle / Naked under Leather (1968). How much you saw of star Marianne Faithfull depended on where you saw it. The U.S. censor came down heavily on the titular fantasizing heroine, the British censor more liberal. Alain Delon co-stars. These says, of course, you can see everything.

- (9) Pharoah (1966). Polish epic set in Egypt sees the country’s ruler at odds with the religious hierarchy.

- (24) A Dandy in Aspic (1968). Cold War thriller with Laurence Harvey as a double agent who wants out. Mia Farrow co-stars.

- (31) Claudelle Inglish (1961). Diane McBain seeks revenge for being stood up at the altar in the Deep South.

- (New Entry) The Family Way (1966). Hayley Mills comes of age in this very adult drama. Co-starring her father John Mills and Hywel Bennett.

- (12) Vendetta for the Saint (1969). Prior to James Bond, Roger Moor was better known as television’s The Saint. Two television episodes combined sees our hero tackle the Mafia.

- (15) Go Naked in the World (1961). Gina Lollobrigida finds that love for a wealthy playboy clashes with her profession (the oldest). Look out for highly emotional turn from the usually taciturn Ernest Borgnine.

- (13) The Appointment (1969). Inhibited lawyer Omar Sharif discovers the secrets of wife Anouk Aimee in under-rated and little-seen Italian-set drama from Sidney Lumet.

- (New Entry) Istanbul Express (1968). Gene Barry plays a weird numbers game in spy thriller that sets him up against Senta Berger.

- (19) Pressure Point (1962). Nazi extremist Bobby Darin causes chaos for psychiatrist Sidney Poitier. Stunning dream sequences.

- (25) Pendulum (1968). Fast-rising cop George Peppard accused of murdering unfaithful wife Jean Seberg

- (11) The Sins of Rachel Cade (1961) Angie Dickinson (again) as African missionary falling foul of the natives and Commissioner Peter Finch. Roger Moore (again) in an early role.

- (16) Diamond Head (1962). Over-ambitious hypocritical landowner Charlton Heston comes unstuck in love, politics and business in Hawaii. George Chakiris, Yvette Mimieux and France Nuyen turn up the heat.

- (27) Fathom (1967). When not dodging the villains in an entertaining thriller, Raquel Welch models a string of bikinis as a skydiver caught up in spy malarkey.

- (36) Prehistoric Women / Slave Girls (1967). Martine Beswick attempts to steal the Raquel Welch crown as Hammer tries to repeat the success of One Million Years B.C.

- (18) The Golden Claws of the Cat Girl (1968). Cults don’t come any sexier than Daniele Gaubert as a French cat burglar.

- (14) The Sisters (1969). Incest rears its head as Nathalie Delon and Susan Strasberg ignore husbands and lovers in favor of each other.

- (17) Moment to Moment (1966). Hitchcockian thriller set in Hitchcock country – the South of France – as unfaithful Jean Seberg is on the hook for the murder of her lover. Also featuring Honor Blackman.

- (New Entry) Age of Consent (1969). Helen Mirren frolics nude in her debut as the freewheeling damsel drawn to disillusioned painter James Mason.

- (28) Farewell, Friend / Adieu L’Ami (1968). A star is born – at least in France, the States was a good few years behind in recognizing the marquee attractions of Charles Bronson. Alain Delon co-stars in twisty French heist thriller featuring Olga Georges-Picot and Brigitte Fossey.

- (35) Horizon: An American Saga – Chapter 1 (2024). Kevin Costner’s majestic western that became one of the biggest flops of the year was underrated in my opinion.

- (New Entry) Genghis Khan (1965). Omar Sharif as the titular warrior up against Stephen Boyd. Co-starring James Mason and Francoise Dorleac. Robert Morley is hilariously miscast as the Chinese Empteror.

- (26) Once a Thief (1965). Ann-Margret again, in a less sexy incarnation, as a working mother whose ex-jailbird thief Alain Delon takes a detour back into crime.

- (29) Woman of Straw (1964). More Hitchockian goings-on as Sean Connery tries to frame Gina Lollobrigida in a dubious scheme.

- (New entry) The Demon / Il Demonio (1963). Extraordinary performance by Daliah Lavi in Italian drama as she produces the performance of her career.

- (New entry) Guns of Darkness (1962). David Niven and Leslie Caron on the run from South American revolutionaries.

- (New Entry) Operation Crossbow (1965). George Peppard is the man with the mission in Occupied France during World War Two. Co-stars Sophia Loren.

- (34) She Died with Her Boots On / Whirlpool (1969). More sleaze than cult. Spanish director Jose Ramon Larraz’s thriller sees kinky photographer Karl Lanchbury targeting real-life MTA Vivien Neves.

- (21) Can Heironymus Merkin Ever Forget Mercy Humpe and Find True Happiness? Fellini would turn in his grave at the self-indulgence of singer Anthony Newley who manages to lament that women falling at his feet cause him so much strife. Joan Collins co-stars.

- (23) The Chalk Garden (1964). Wild child Hayley Mills, trying to break out of her Disney straitjacket, duels with governess Deborah Kerr.

- (New Entry) Dark of the Sun / The Mercenaries (1968). Rod Taylor’s guns-for-hire break out the action in war-torn Africa. Jim Brown and Yvette Mimieux co-star.

- (New entry) La Belle Noiseuse (1991). Emmanuelle Beart is the mostly naked model taking painter Michel Piccoli to his artistic limits.

- (New Entry) A Fine Pair (1968). Rock Hudson and Claudia Cardinale join forces for a heist picture.

- (33) Lady in Cement (1969). Raquel Welch models more bikinis as the gangster’s moll taken on as a client by private eye Frank Sinatra in his second outing as Tony Rome.

- (New Entry) Carry On Up the Khyber (1968). The most successful of the Carry On satires poking fun at the British in India.

- (New Entry) The Venetian Affair (1966). Robert Vaughn investigates spate of suicide bombs. Elke Sommer provides the glamor.

- (22) The Secret Ways (1961). The first of the Alistair MacLean adaptations to hit the big screen features Richard Widmark trapped in Hungary during the Cold War. Senta Berger in an early role.