Count me in. The buddy movie reinvented, the MCU legend trashed, all set in the ideal MCU location, The Void (worthy of two capital letters, I guess), the place where long-forgetten Marvel characters from the pre-Disney multiverse hang out, and it’s a fun ride. Whether of course this proves the death knell for the MCU after so much fan backlash and poor reviews remains to be seen. Next weekend’s box office will decide its fate one way or another.

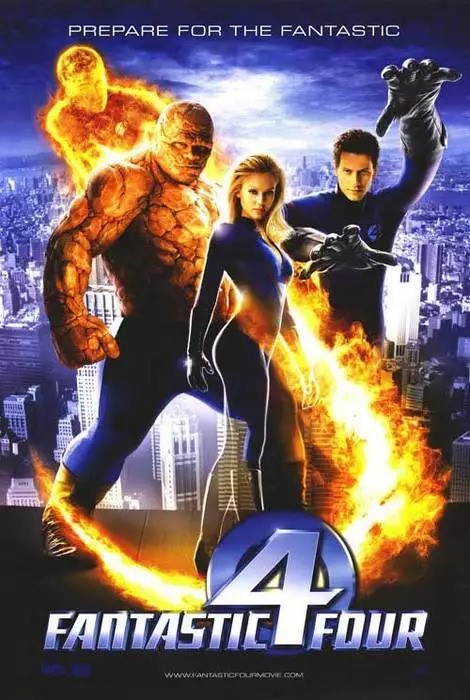

But who the hell cares? If this is the extinction of the MCU, as some predict, then it is going out with a bang, a crazy superhero mash-up where you need to keep an MCU dictionary to hand so you can work who’s going to turn up next. Wesley Snipes, not seen in that Blade badass rig since 2004, and it’s not Capt America but Chris Evans’ earlier incarnation of Johnny Storm not seen since 2007, and there’s Channing Tatum as a character Gambit whose stand-alone picture never materialized, despite scoring highly in animated form.

Anything that MCU got wrong or was criticized for – the multiverse and the varying timelines – turn up here as plot. The “sacred time lime” is almost a character in itself and if you ever wanted to invent the most ideal/ironic MCU character, who else would that be but Mr Paradox (Matthew Macfadyen)?

The entire storyline is so off-the-wall that you’d think it’s never going to work but then when Deadpool’s around walls are toys, especially the fourth wall, that magical trick of speaking direct to the camera. And it’s Deadpool and his continual wisecrack commentary on proceedings that turns what could be a s**tshow into a hoot.

But some of the twists transform what could be another deathly routine of superheroes saving the universe (yawn, what again?) into something more human. Deadpool (Ryan Reynolds) only wants to save his own tiny universe of half a dozen people, everyone who matters to him, and not a gazillion others. Somehow he teams up with the previously deceased Logan a.k.a. (in case you don’t have your MCU Dictionary handy) Wolverine to revive the moribund buddy movie, the best kickass bickering pair since Mel Gibson and Danny Glover in Lethal Weapon.

Or whatever. Anyway, they find themselves in The Void doing battle with that sweet Charles Xavier guy’s nasty twin sister Cassandra Nova (Emma Corrin). And, yes, there’s still so much jiggering about with time that you’d think the Time Bandits or Doctor Who would be claiming copyright infringement. And sometimes you can almost hear the clack of the typewriter as the screenwriter tries to fix that last loose end.

But, as I said, whenever the going gets tough – especially when the going gets tough – you can depend on Deadpool’s motormouth to see the narrative through. Deadpool and Wolverine do make a great screen team, ideal opposites, growl vs grit, class vs. sass, and really you could just junk the narrative – or come up with an entirely different one – and still this picture would work because the two principles set the screen alight.

This is akin to when Guardians of the Galaxy ripped up the MCU playbook a decade ago and influenced every movie thereafter. The guess now is whether Deadpool and Wolverine will take MCU down a new stylistic avenue or whether this is a deliberate cul de sac. I’d guess not, since it’s going to be such a money-spinner, and I could see this pair worming their way into the new Avengers team to brighten up whatever doom-laden occasion is heading our way.

Maybe the MCU is giving the finger to the fanboys, hoping to attract a wider audience rather than pandering to an audience that seemed to have made up its mind about everything way in advance and wasn’t inclined to go along with any MCU experiment, feint or development. The audience I saw it with were clearly of mixed opinion, some feeling betrayed or at the very least insulted.

But I have a good bit less invested in the MCU. It takes me all my time to keep up with who’s who in this expanding universe. So treating this picture on its own merits, I thought it generated more than its fair share of laughs, and not always rude ones, although anyone with a woke inclination would be advised to steer clear.

Shawn Levy (Free Guy, 2021) directed.

Make up your own mind.