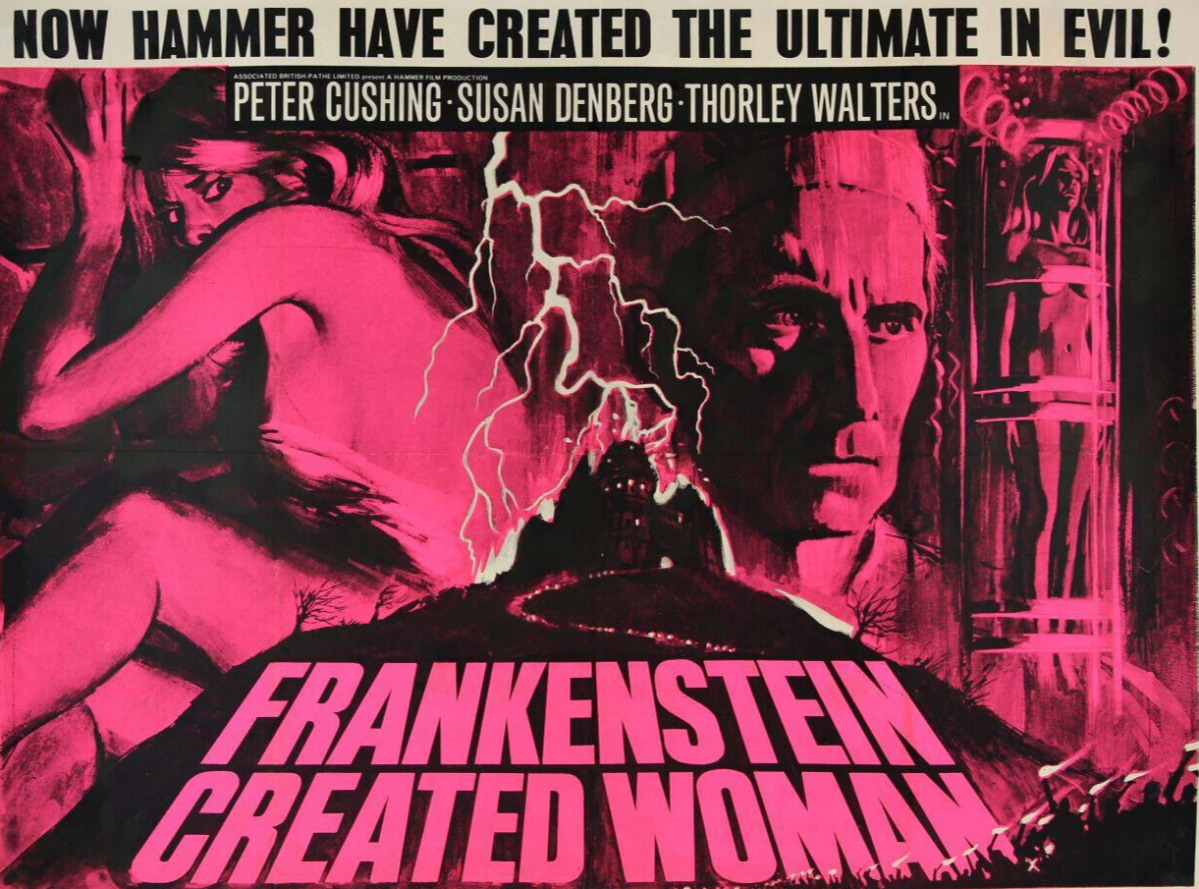

Custom-made for a contemporary audience. How can you fail with a tale about a male brain taking over a female body. Male soul if you want to be strictly correct and metaphysical about it or if you are Martin Scorsese for whom discussion about whether the soul leaves the body after death and exists on some other plane was of the greatest interest. But, yes, so although our hero/villain Baron Frankenstein (Peter Cushing) does create a female instead of a male, and not just with the misogynistic purpose of supplying a monster with a mate, unfortunately in the act of creation the poor woman is saddled with the soul/brain of a man, and, even worse, one with bloody revenge on his mind.

These days for sure audiences would not have any trouble with female stars carving a swathe through any populace and nobody would require transplanting of male hormones-soul-brain-whatever to take off on a rampage. But, back in the day, before Hammer went full-tilt-boogie down the lesbian vampire route, it was rare, outside of film noir and exploitationer pictures, for a woman to be so savage. So her actions are viewed with regret rather than roars of approval. But, for once, nobody is taking a torch or axe to the good old Baron.

That’s not all that takes the audience by surprise. The use of a guillotine, ideal for a post-task dripping of blood, turns out to be widely used in central Europe in the 19th century, hardly surprising since it was a German invention. The movie opens with a young boy, Hans, witnessing his father’s execution on such a device, a point that seems arbitrary but proves pivotal.

The grown-up Hans (Robert Morris) assists Dr Hertz (Thorley Walters) assisting the Baron in some kind of resurrection experiment, the guinea pig being Frankenstein himself. Naturally, for purely metaphysical purposes you understand, the Baron would like to experiment on as barely-dead a cadaver as possible to prove his theories. That this takes a good while to materialize is largely because the narrative has to go all around the houses.

Hans’s lover, disfigured and lame innkeeper’s daughter Christina (Susan Denberg), is taunted by a trio of young swells that results in Hans attacking them. Later, for no particular good reason, the toffs kill the innkeeper, but Hans gets the blame and is sentenced to death. After he is guillotined, Christina commits suicide by drowning. Both bodies turn up in Frankenstein’s lab at roughly the same time. Complication of course being that a guillotine doesn’t deliver a body intact. Quite how Frankenstein achieves his soul-body transplant is left up to your imagination – the scene promised in the poster is a marketing fiction.

And there’s a touch of Poor Things about the result as Christina wakes up minus scars and disfigurement but with no recollection of her past and needs to be taught who she is. Not that she requires much education in the feminine wiles department and is soon stalking the three young toffs, seducing them with hints of sexual promise before taking savage revenge.

There also a Curse of the Undead element when villagers discover her grave is empty. In fairness to the Baron, he soon realizes what fate had befallen her and tries to ensure that, once her revenge is complete, she can live a different life, although in the way of horror films a happy ending is rarely an option. And in fairness to the Baron the villagers aren’t queueing up to set him alight.

With various subplots to get through, this leaves the Baron out of the picture for considerable periods of time. From a contemporary perspective, there’s a freshness here that will appeal, especially the creation’s desire to discover her purpose in life, her not being bred to fulfil a romantic purpose, and the battle of the male-female will.

Peter Cushing (The Skull, 1965) is as usual splendid, Thorley Walters (Sherlock Holmes and the Deadly Necklace, 1962) presents as an inebriated and impecunious assistant while Austrian Susan Denberg (An American Dream, 1966) does well in the dual role.

Fourth outing in the Hammer series, directed with occasional verve by the reliable Terence Fisher (The Devil Rides Out, 1968) from a screenplay by Anthony Hinds (The Mummy’s Shroud, 1967).

Contemporary appeal and can never go wrong given that it is purportedly one of Martin Scorsese’s favorite films.