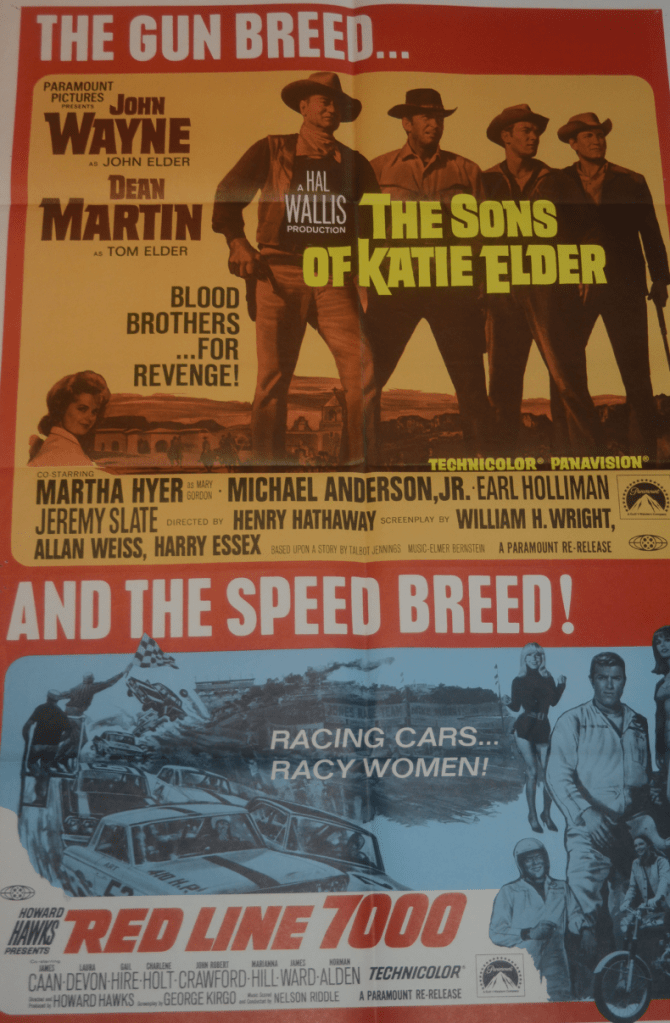

Quentin Tarantino is probably alone in preferring this movie mishap to John Frankenheimer’s Grand Prix (1966) – or I have somehow missed a “cult” picture. There was no doubt director Howard Hawks could handle speed. Check out the action in Hatari! (1962) as jeeps battle across tougher terrain than NASCAR racing circuits. But for some reason, he thought he would get away with interspersing footage of races and spectacular crashes with shots of actors behind the wheel. Any time something exciting is about to happen we’re alerted by the commentator saying “oh oh” or “wait a minute” or “hold it.” There’s none of the feverish excitement or authenticity of Grand Prix.

Hawks hired a no-name cast in a bid a) to become a star-maker, b) to prove he did require the marquee wattage of the likes of John Wayne and c) to show he could make a movie cheaply. He failed on all three counts. He probably didn’t think he was taking any kind of gamble at all, as a man approaching 70, in trying to depict the lives of people around 50 years younger. James Caan, in his sophomore outing, comes out best, but that’s not saying much since he has very little to do except growl and look broody. Marianna Hill (El Condor, 1970) is also believable.

While the racing footage has dated in a way that Grand Prix has not, the main problem is just a jumble of characters getting lost in a jumble of stories. No sooner has one character been introduced than we are onto another. There’s none of the cohesive story-telling that marked out The Big Sleep (1946) or Rio Bravo (1959) and, frankly, none of the characters are particularly interesting. And what possessed him to stick in a song sung by a character (Holly, played by Gail Hire) who cannot sing – she talks the lyrics – with a backing group made up of waitresses, I can’t begin to guess.

The most fun to be had is spotting in bit parts people famous for other reasons. Carol Connors, for example, who co-wrote the lyrics to “Gone Fly Now” (Rocky, 1976) appears as a waitress. As does Cissy Wellman, daughter of veteran director William Wellman. Comedian Jerry Lewis has a cameo. It says much for Hawk’s star-spotting abilities that of two female leads, Laura Devon only made five pictures and Gail Hire just two.

Of the main supporting males, this was the beginning and end of John Robert Crawford’s movie career while Skip Hire made a bigger splash as a producer of television series The Dukes of Hazzard. Co-written by the director, George Kirgo (Spinout, 1966) and Steve McNeil (Man’s Favorite Sport, 1964)..

However, the French had a word for it – “genius.” Despite being dismissed as a rare misstep by the bulk of critics worldwide, Cahiers du Cinema decided it was one of the year’s Top Ten pictures. So what do I know?