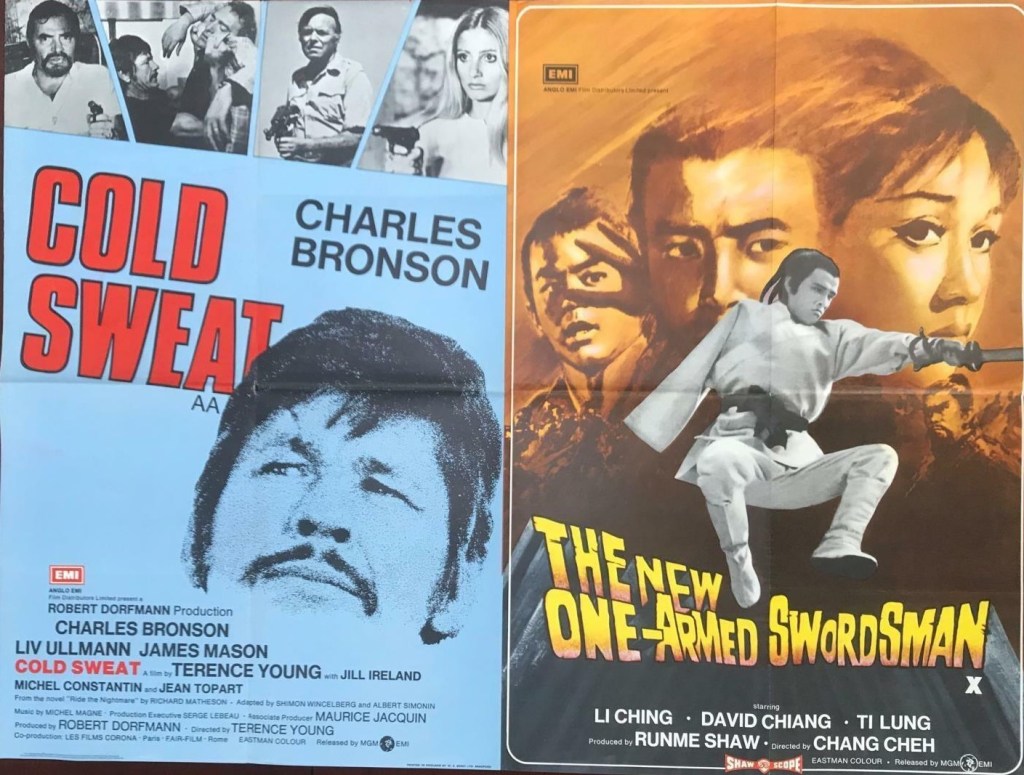

One great scene doesn’t make a great movie, but I’ll tell you about it anyway and we can all wonder what went wrong with the rest of the picture. Through a swinging louvre door we catch glimpses of Joe (Charles Bronson) putting a headlock on a thug. The motion of the door slows down as the villain is slowly choked to death. As the door closes we cut to Joe’s terrified wife Fabienne (Liv Ullman) and watch her reaction as she hears the neck snap.

Pretty good, eh? If only the rest of the movie were in that class. Except for a rollicking good car chase, it’s hampered by an over-complicated plot, kidnappings in retaliation for kidnappings, a dippie hippie (Jill Ireland) and one of the worst accents you will ever hear – quite why director Terence Young (Mayerling, 1969) wasn’t able to tell James Mason that his American South impersonation didn’t cut it is anybody’s guess.

the kung fu picture was a stronger attration.

Joe charters out a yacht in the south of France, but prefers gambling and drinking to spending evenings with his wife. But then his past catches up with him. Cue complicated backstory – he was a soldier who got mixed up in a robbery but ran away from the theft when the going got tough and was the only one who escaped a jail term. Now his old buddies want revenge but will accept instead Joe doing another job for them.

Joe doesn’t agree so Captain Ross (James Mason) kidnaps his wife and child. So Joe kidnaps the captain’s girlfriend Moira (Jill Ireland), stashing her away in a remote cabin filled with creepy-crawlies where she has “nothing to eat but money.” So they do a trade, except Ross reneges, and then gets shot, potentially leaving wife and child at the mercy of his creepy sidekick.

There’s a fair bit of action, and when Joe is beating people up or driving like crazy over inhospitable terrain, it makes like a thriller but when he’s left to try and lift a flare gun up with his foot it’s on shakier territory. The two elements of the story split too quickly and while wife and daughter make the most of being scared out of their wits, terrified women aren’t what people come to see a Bronson picture for.

So it’s too much of a mixed bag. To compensate for the dire Mason (A Touch of Larceny, 1960), Liv Ullman offers a fresh perspective on the female lead in a Bronson picture, an actress who can actually act, her extremely expressive features meaning she doesn’t need to over-act. In her first mainstream picture, Ullman junks the Ingmar Bergman angst and comes across as a normal wife and mother thrown into a desperate situation. Her presence lightens up Bronson, though at this stage in his career, as evidenced by Someone Behind the Door (1970), Violent City / Family (1970) and Red Sun (1971), he presents quite a different screen persona to the grimacing/growling that was his post-Death Wish (1974) trademark.

Young seems caught between the action of his James Bond trilogy and the emotion-led drama of Mayerling and falls between two stools and hadn’t quite worked out how to get the best out of Bronson, a problem he rectified in Red Sun. Based, theoretically, on a novel by Richard Matheson (The Devil Rides Out, 1968), the screenplay has gone through too many hands, four at the last count, which probably accounts for the dodgy plot.

Not Bronson at his best, probably not a highlight of Ullman’s career either, and definitely a low point for Mason.

For Bronson completists only.

NOTE: There’s a vicious rumor going round, spread on Imdb, that this movie ended up on television only three days after cinematic release. Total nonsense of course. It was released in Britain in July 1973, gaining a two-week London West End run at the ABC-2 (“West End Soars, Variety, July 25, 1973, p19) and going out on a circuit release. It failed to find a U.S. distributor until 1974 in the wake of the success of Death Wish whne it was given a PG certificate by the Motion Picture Code and Rating Program and subsequently distributed by independents like Marcus Film and Emerson. It premiered in Denver – seen as a testing ground for difficult pictures, the city viewed “as a good barometer” of how movies will perform nationwide – in May 1974 (“Denver Used As Testing Ground For New Movies,” Box Office, May 20, 1974, pW4). Total rentals were estimated at around $250,000 (“Variety Chart Summary,” Variety, May 7, 1975, p134) and it placed 247th in the chart. It made its U.S. television debut on ABC in February 1975. (“Only ABC Enters Second Season With Quantity of First-Run films,” Variety, January 29, 1975, p43) but didn’t score highly with viewers finishing in 119th place for the year (“Theatrical Movie Rankings 1974-1975,” Variety, September 17, 1975, p40).