Bold examination of racism years ahead of its time. Narrative not sweetened for audiences by a detective story (In the Heat of the Night, 1967) or grumpy father-of-the-bride comedy (Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, 1967) or by protagonists unrepresentative of society by being criminal (The Defiant Ones, 1958) and criminally insane (Pressure Point, 1962), the issue of racism – miscegenation and interbreeding – smack bang in the middle. Though it takes place in Hawaii, theoretically at one remove from the violence emanating in the U.S. Deep South, the points made strike home.

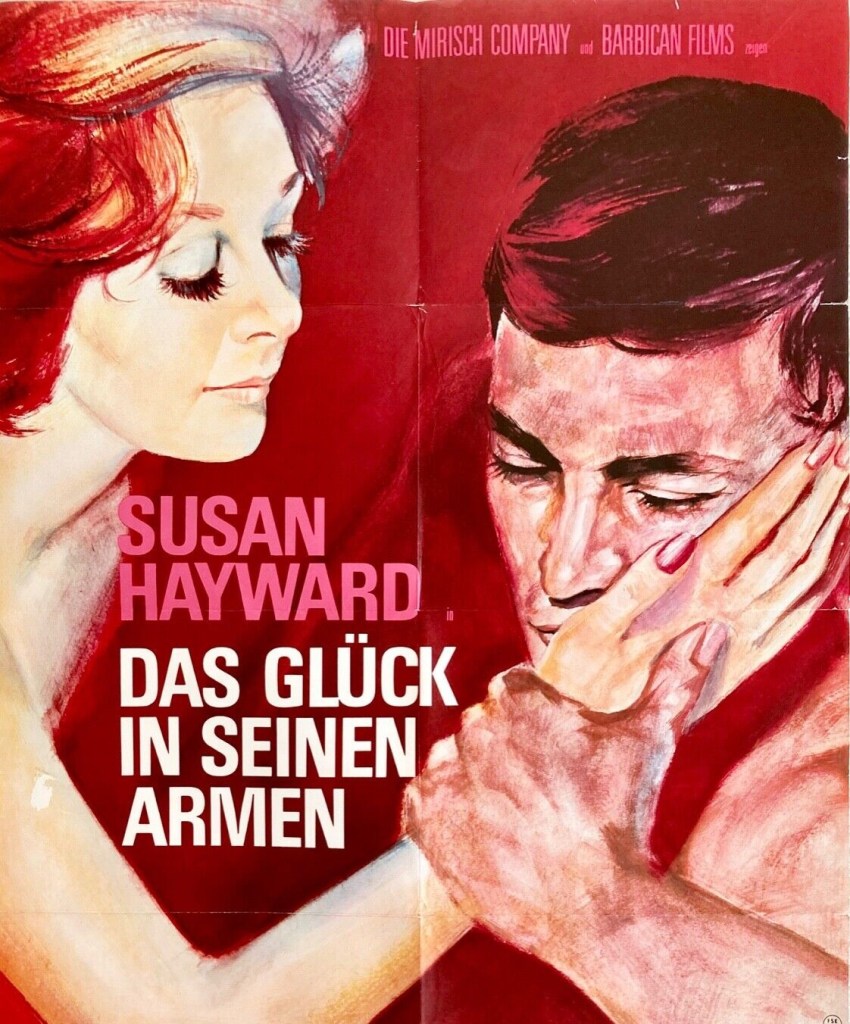

If a shade melodramatic, that is undercut by a set of very fine performances by all the principals. Charlton Heston, later lacerated in democratic circles for his defence of the right to bear arms, here employs his marquee value to deal with the ticking time bomb.

The tale is simple enough. Headstrong Sloane (Yvette Mimieux) decides to marry native-born Paul Kahana (James Darren) against the wishes of her older brother, widowed millionaire landowner “King” Howland (Charlton Heston). Despite using equality as an election platform in a bid to become a Senator, King fiercely objects to the marriage on the grounds that it will dilute his bloodline and, in effect, hand over control of his empire to an outsider. His spinster sister-in-law Laura (Elizabeth Allen) backs him on this score as does, oddly enough, Paul’s mother Kapiolani (Aline McMahon) who complains that interbreeding has reduced the number of native Hawaiians to a mere 12,000.

Complicating matters is King’s hypocrisy. His mistress, Mai Chen (France Nuyen), already is of mixed parentage. But when she announces she is pregnant, he demands she have an abortion. Spicing up that particular complication is her brother Bobbie (Marc Marno) who sponges off the perks King provides and now decides to hit the gold seam by blackmailing King. And just in case that’s not enough in the way of complications Sloane has always had a yen for Paul’s older and more successful brother Dean (George Chakiris), now a hospital doctor. In fact, as outlined in a flashback, Paul was decidedly second-best in Sloane’s eyes and there is a hint she romanced him to spite the more sensible brother.

Bobbie doesn’t get the chance to put his scheme into practice as he is implicated in the death of Paul, who had been trying to stop the blackmailer from drunkenly attacking King at a traditional engagement ceremony. Paul is killed accidentally by King.

That should have simplified matters, but it doesn’t. King is abandoned by Sloane and Laura leave and Mai Chen throws him out. The scandal of Paul’s death should have ended his political ambitions, but despite his backers dropping out, arrogantly he decides to go it alone until receiving the slow-handclap treatment from the public. He is fully aware of the consequences of his action, pointing out that $3 million spent on philanthropy wouldn’t “buy me a tear.”

It could have ended there, proud man brought down by ambition, institutional racism and stubbornness, but it follows a different, and reconciliatory, tack at the end.

And it could have been a heaving brew of melodrama with dilated nostrils and screaming matches but it’s redeemed from that by most of the actors downplaying their roles. There is some impressive playing by Charlton Heston (55 Days at Peking, 1964) who carries off his hypocrisy in some style, but doesn’t descend to the obvious ploy of disinheriting the defiant one or at the very least chucking her out and generally manages to keep the lid on his temper. George Chakiris (Flight from Ashiya, 1964) uncannily captures all the elements of his character. An educated man so can’t be downtrodden but has to watch his step in confronting such a powerful man, so he makes his point with quiet determination.

In an early starring role Yvette Mimieux (Joy in the Morning, 1965) is given a lot more to do than in some later offerings. She exhibits defiance not just in regard to racism but sexism as well, determining that her marriage would be an equal relationship not one where she would be subservient to her husband. Had she been able to rein in her pig-headedness and present herself as more interested in the business than its perks she might have allayed her brother’s fears that in endorsing the marriage he was risking handing over his empire to her idiot husband, so lacking in the brain department he needed extra years to graduate at college.

France Nuyen (Man in the Middle, 1964) has a peach of a part, plenty good lines, and the beneficiary of the few scenes not driven by narrative requirements, in particular her observations at watching her lover dress. James Darren (The Guns of Navarone, 1961), given less to do, is not surprisingly more of a cliché. Oscar-nominated Alice McMahon (Cimarron, 1960) is quietly impressive as the equally torn parent who could, at one point, take legal revenge on King.

Director Guy Green (The Magus, 1968), aware the content is inflammatory enough without the principals going overboard, does pretty well to stick to the issues. Screenwriter Marguerite Roberts (5 Card Stud, 1968), in adapting the bestseller by Peter Gilman, makes several changes to keep the focus on the key element.

In his diary, Charlton Heston noted that that movie was overly melodramatic but with the proper treatment it could work. He was right. The plot has more cogs than any wheel could comfortably accommodate, but by keeping the central issue central the movie would be viewed today as the highpoint of Hollywood’s opposition to racism rather than being superseded five years later by the pair starring Sidney Poitier.