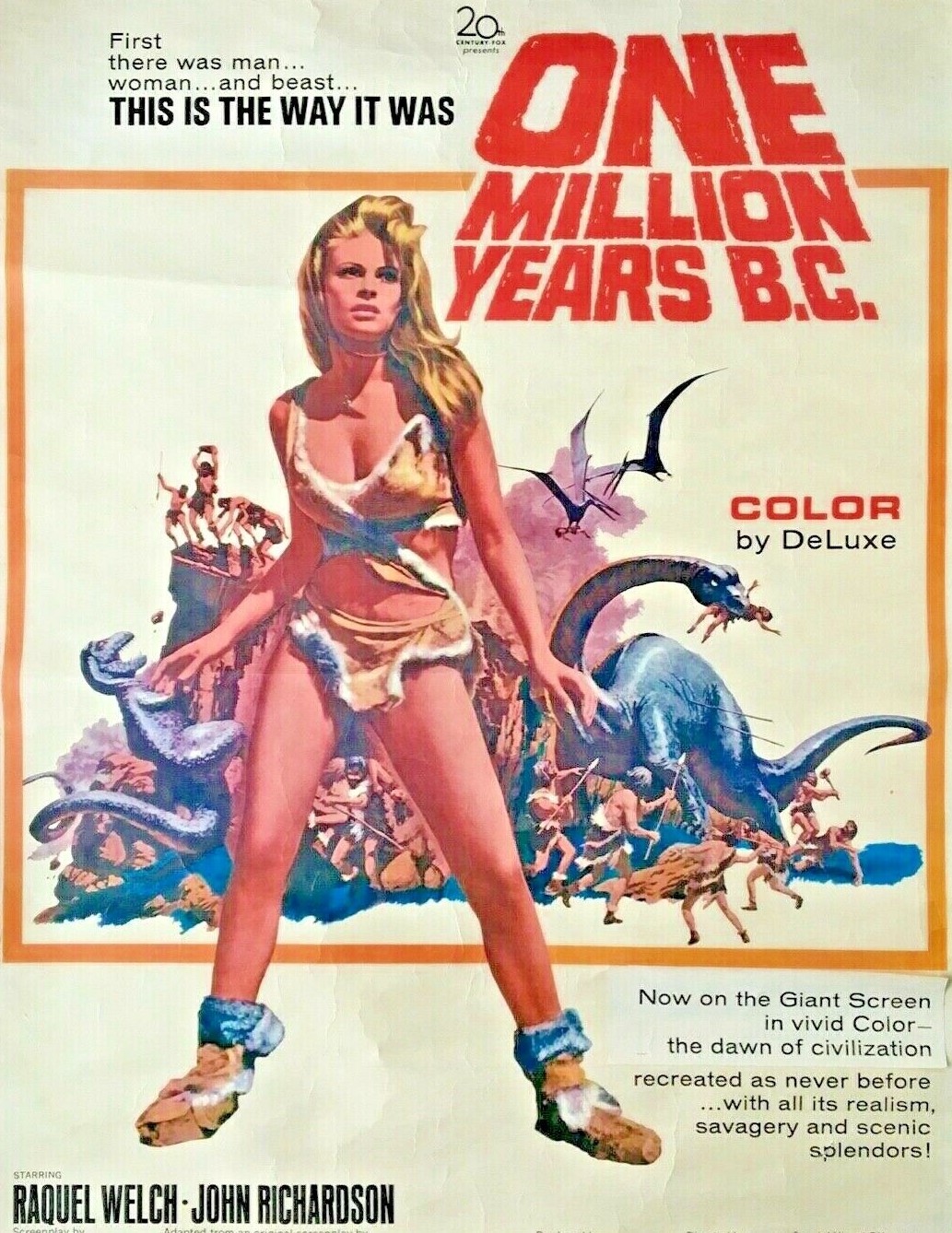

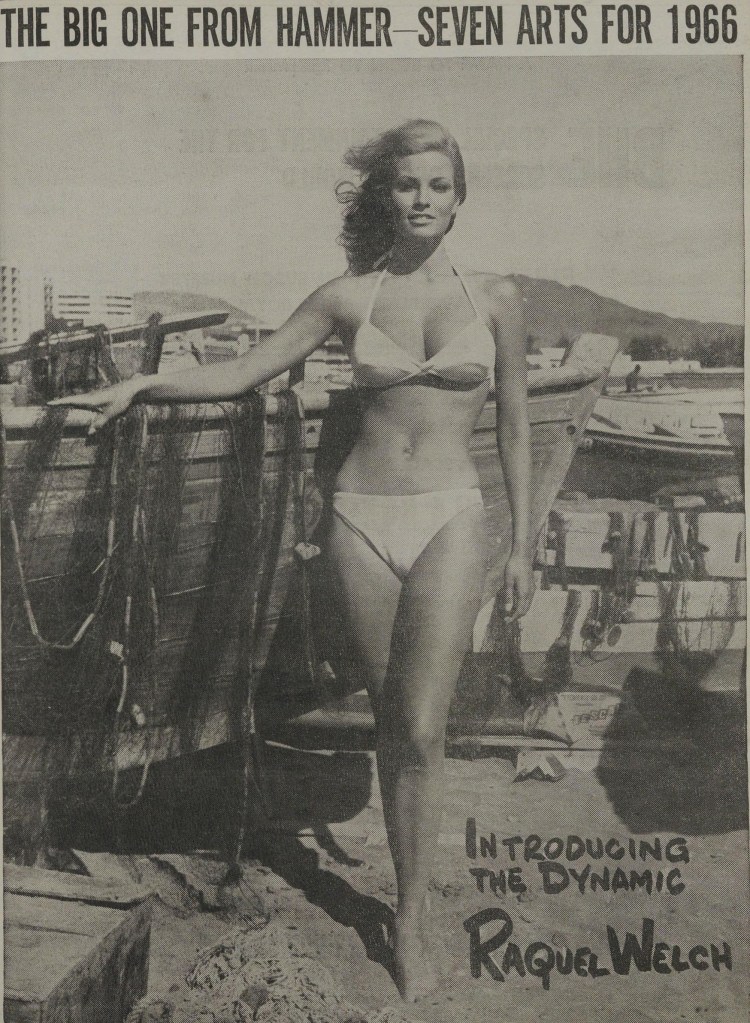

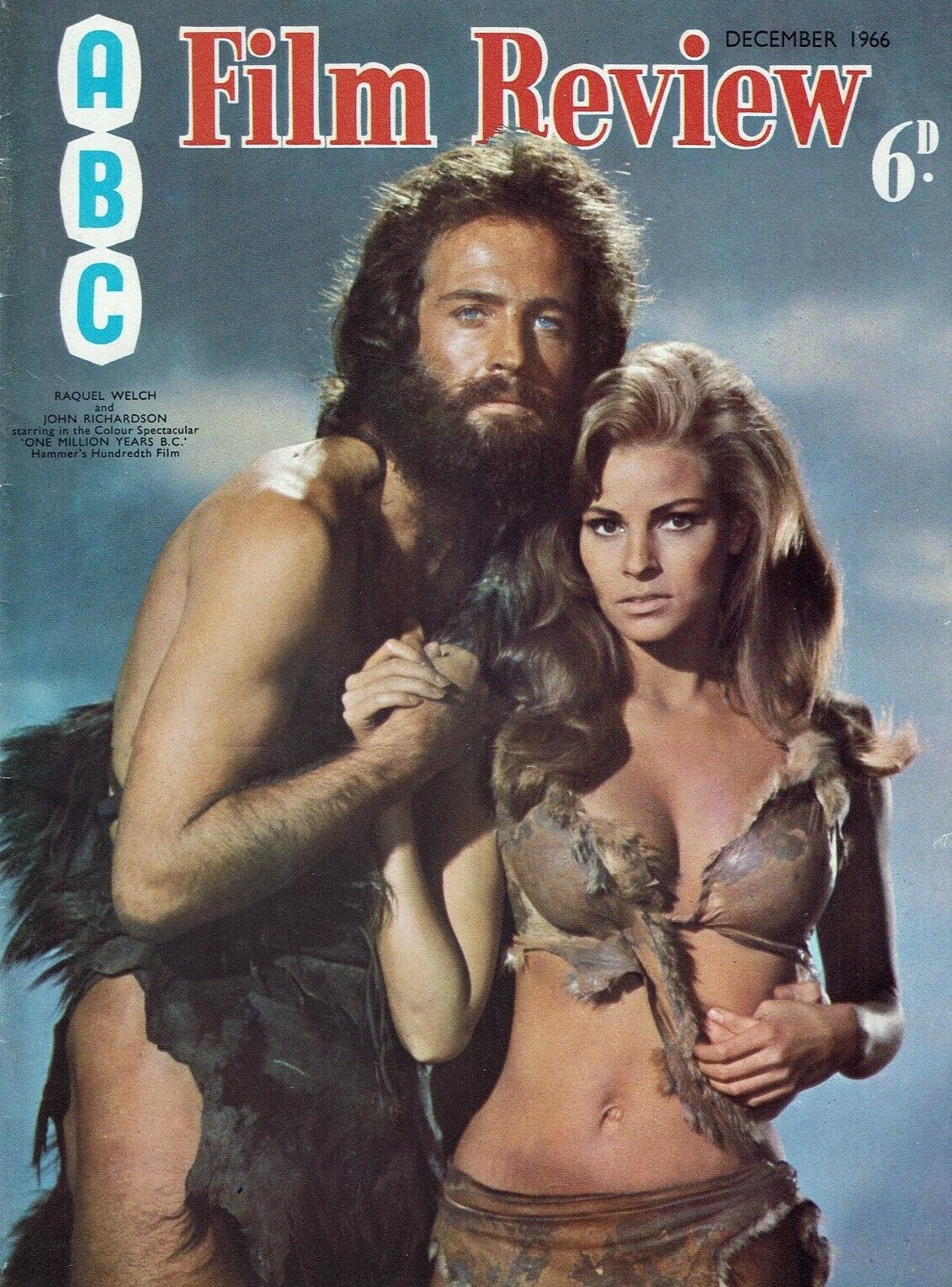

Despite being sold to television within a few years of initial release, as was standard at the time, One Million Years B.C. enjoyed an exceptionally long big-screen life, still available in reissue over a decade after premiere. Although a highly successful reissue double bill with She (1965) in the British home market in 1969, that revival did not strike gold in the U.S. One Million Years B.C. had enjoyed a surprisingly successful launch in the U.S., beating the Thunderball record at the New Amsterdam theatre in New York and going on to hoist $2.5 million in rentals putting it ahead in the annual box office race of A Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More and Point Blank.

Factors in its unexpected longevity included: proving a natural stablemate for movies set in the distant past or distant future, as double bill material for other Welch product, and supporting other Fox new releases. It was a studio workhorse. In 1967, it supported western Hombre, gangster picture The St Valentine’s Day Massacre, comedy Caprice, war epic The Blue Max and a revival of Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines. The following year it backed Frank Sinatra in Tony Rome, Walter Matthau comedy Guide for the Married Man, Steve McQueen big-budgeter The Sand Pebbles, Sinatra again in The Detective, The Bible and hoping-to-be-hip The Sweet Ride. Roll on to 1969 it was the support to westerns Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and The Undefeated.

And that should have been the end of its big screen career. By then it had been shown on television, on ABC, the second best program of the week. So, in theory at least, that should have been the end of exhibitor interest.

But it wasn’t. Come 1970 and it turned up in a triple bill of Butch Cassidy and The Boston Strangler, was geared up as support to Mash and Patton, and another triple bill, Butch again, with The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. Butch Cassidy was its partner again in 1971.

Outside of the Twentieth Century Fox connection, there were sorties with She and its sequel The Vengeance of She, and The Lost Continent, a triple bill with Hammer stablemates The Viking Queen and Prehistoric Women, and in 1970 with She and Goliath and the Seven Vampires plus the following year a quadruple bill featuring The Viking Queen, The Vengeance of She and Five Million Miles to Earth.

The following year it turned up as support to When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth (“from the creators of One Million Years BC”), The Creatures The World Forgot, and the original King Kong (1933). In future years there were triple bills with Tarzana the Wild Girl and Prehistoric Women and with The Valley of Gwangi and Earth vs Flying Saucers.

With striking regularity it was teamed up with Planet of the Apes, Beneath the Planet of the Apes, Escape from the Planet of the Apes, Conquest of the Planet of the Apes and Battle for the Planet of the Apes.

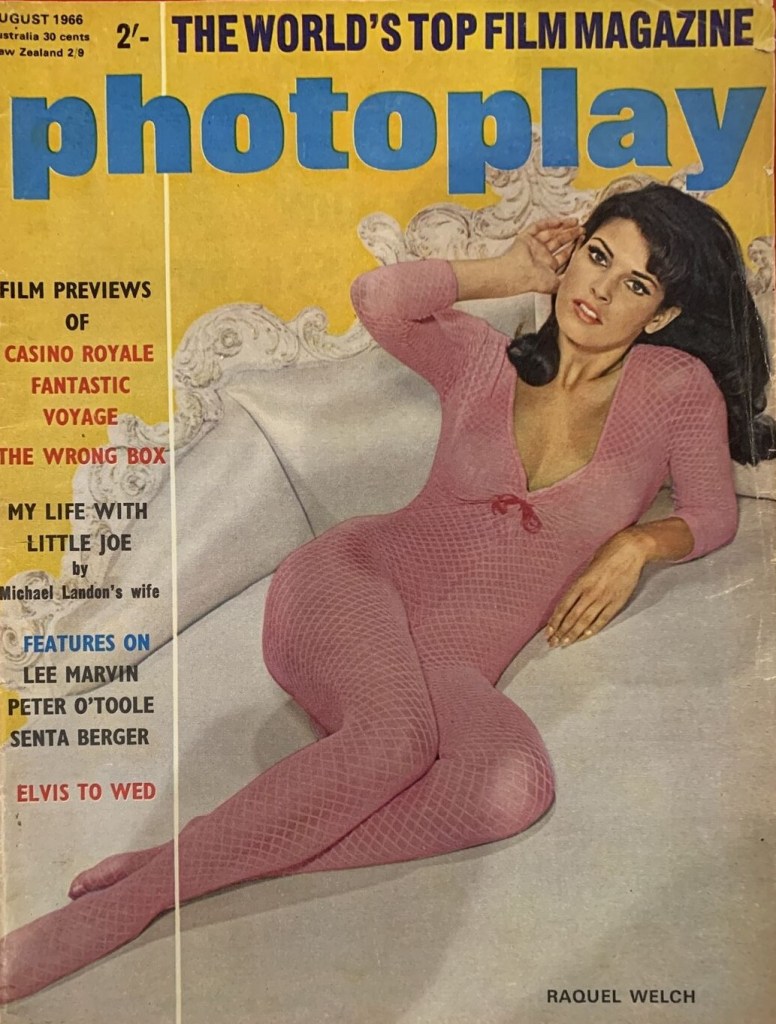

Elected to form a Welch double bill with One Million Years B.C. were Fantastic Voyage (various bookings over 1967-1969), Fathom (1967-1968), The Biggest Bundle of Them All, 100 Rifles, Bandolero and The Three Musketeers (1974) while a Welch triple bill in 1973 augmented the dinosaur picture with Fantastic Voyage and Lady in Cement.

While Fox had first call on its services, at a certain point the studio relinquished exclusivity and exhibitors were free to book it whenever they wanted, Fox content to make a few extra bucks every time. So it went out with Paramount westerns El Dorado with John Wayne and Robert Mitchum and Five Card Stud with Robert Mitchum and Dean Martin, Disney animated feature The Jungle Book and its revival of In Search of the Castaways, UA war picture The Devil’s Brigade, comedy Inspector Clouseau and football drama Number One, MGM comedy The Maltese Bippy, big-budget war spectacular Where Eagles Dare with Clint Eastwood and Richard Burton and the reissue of Ben-Hur, NGC comedy How Sweet It Is, Columbia’s space drama Marooned, French political thriller Z, Harry Alan Tower’s jungle adventure Eve and the British sex drama All Neat in Black Stockings. The last sighting I made of it was with sci-fi Futureworld in 1976.

Add One Million Years B.C to Ben-Hur and you’re talking a near-five-hour program, four hours for Where Eagles Dare. You can see from the indiscriminate double bills that nobody was trying to find the ideal match. Exhibitors didn’t have to, Raquel Welch and her fur bikini had something everyone wanted, a picture that moviegoers were happy to see again and again.

Where were you when you first saw One Million Years B.C.? And what age? And what gender? Did you see it on the small screen or the big, on original release or a reissue?

SOURCES: Brian Hannan, Coming Back to a Theater Near You, A History of Hollywood Reissues 1914-2014 (McFarland, 2016), p208-210; “Georgy, Flint in ABC Film Line-Up,” Variety, April 30, 1969, p35. Box office figures Variety: August 2, 1967, p 11; August 16, 1967, p10; Jul 21, 1971, p8. Listings in Newspapers: Argus, Fremont; Evening Standard, Uniontown; Valley News, Van Nuys; Independent, Long Beach; Kingsport Times; Standard-Examiner, Ogden; Des Moines Register; Tucson Daily Citizen; Abilene Reporter News; Kansas City Times; Wellsville Daily Reporter; Morning Herald, Uniontown; San Antonio Express; Aniston Star; Manhattan Mercury, Kansas; Gastonia Gazette; El Dorado Times; Fresno Bee; Gallup Independent; Post-Standard, Syracuse; Arizona Republic; Daily Times, Salisbury, Maryland; News Journal, Mansfield, Ohio; Corpus Christi Caller; Naples Daily News, Florida; Journal News, Hamilton, Ohio; Statesville Record and Landmark, North Carolina; Hamburg Reporter; Beckley Post-Herald; Brownsville Herald; Nashua Telegraph; Portsmouth Herald; Delta Democrat-Times; South Illinoisian; Terre Haute Tribune; Pasadena Independent; Xenia Daily Gazette; El Paso Herald-Post; Cumberland News, Maryland; Delaware County Times; and Northwest Arkansas Times, Fayetteville.