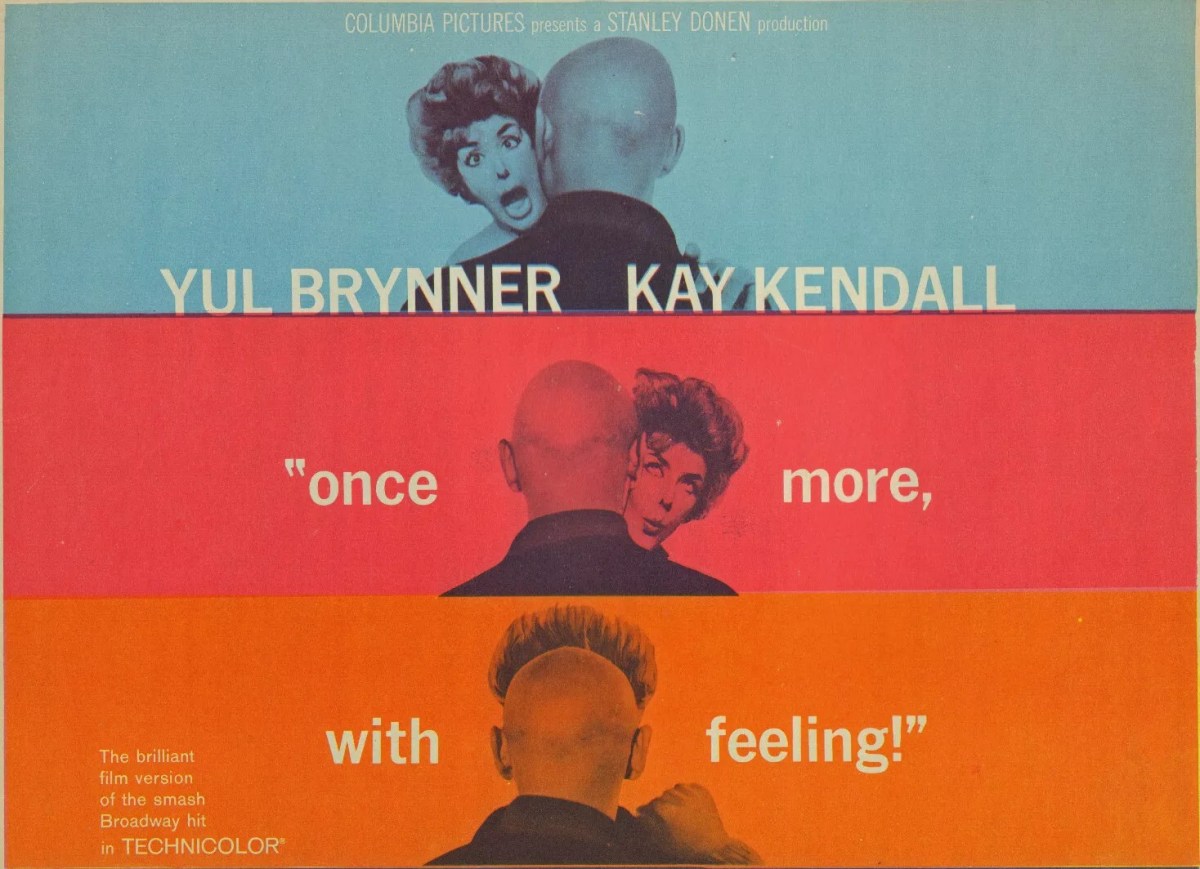

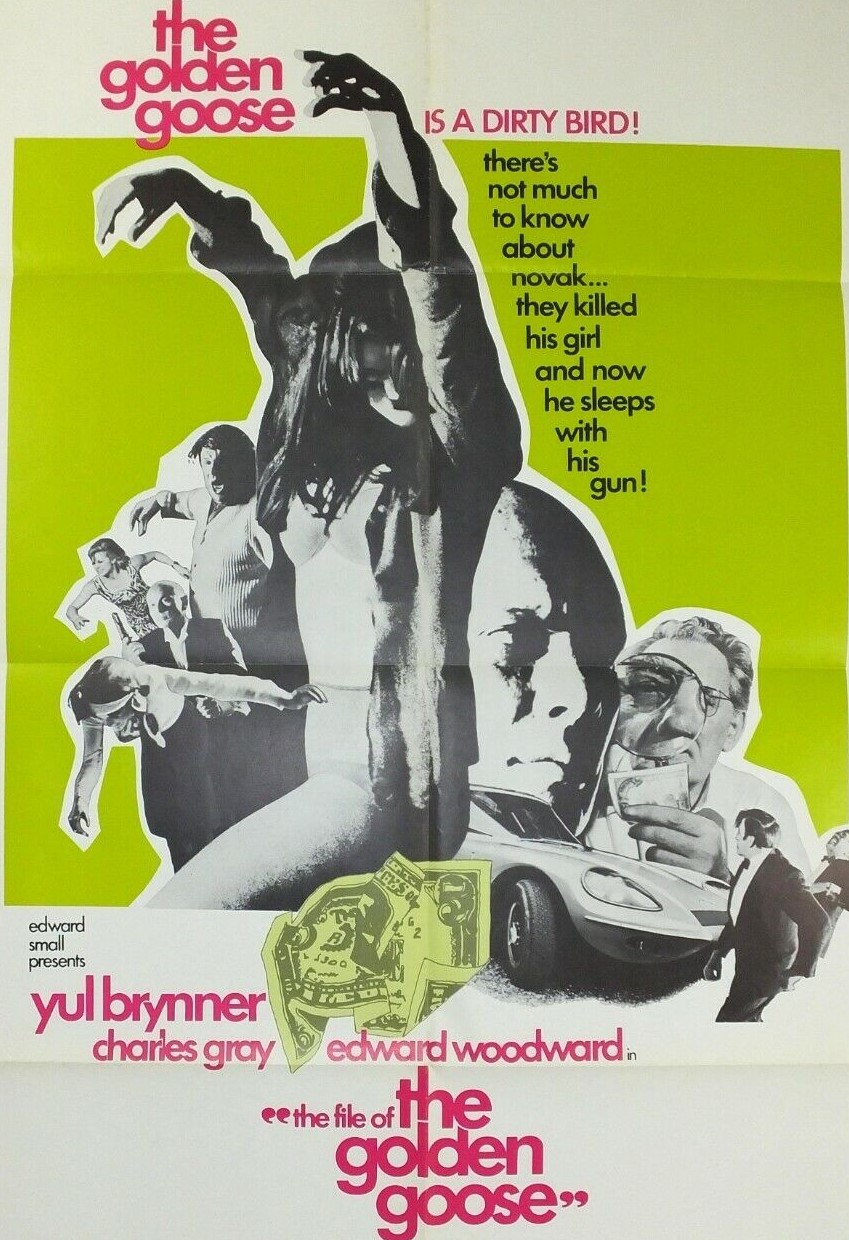

Poses two questions. Is this every bit as bad as Once More with Feeling, Stanley Donen’s previous picture? Yep, sorry, it’s every bit as wretched. The second question is: how on earth did Donen go from this mess to sublime romantic thriller Charade three years later? Well, the answer might simply be in the casting. Yul Brynner is no Cary Grant. And in this movie he’s not even Yul Brynner.

My guess is he’s meant to be a humorous twist on the Brynner screen persona. But playing a gangster with a thick Noo Yoik accent was always the preserve of the dumb supporting actor not the star. And since Yul Brynner isn’t any more convincing in this than in Once More with Feeling the project is in trouble from the start.

We’re given too much of this faux gangster drivel at the start when mob kingpin Nico (Yul Brynner) is collecting tributes from his underlings. Then, for no particular reason, he is deported, sent back into exile to his homeland of Greece. There he encounters the only smart guy in the picture, the corrupt chief of police Stefan (Eric Pohlmann) who’s so astute in the bribery department that all Nico receives in return for his thousand dollar bribe is to be told he won’t be arrested for bribery.

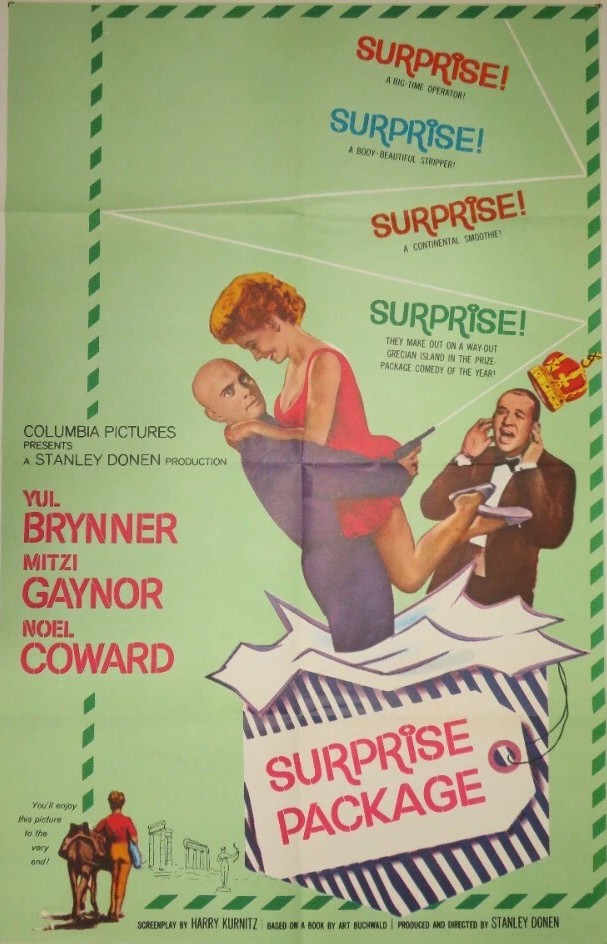

Stefan sets up Nico to meet another exile, deposed King Pavel II (Noel Coward), whose accent makes no sense either unless he was exclusively raised in high class British society, schooled at Eton, a member of upper class clubs etc etc, otherwise how to explain the plummy tones unless this is also meant to be as over-the-top gag as Nico’s Noo Yoik accent. Nico plans to buy the king’s crown for a million bucks. But the boys back home stiff him and instead of the cash send him instead his girlfriend – the surprise package of the title – mob moll Gabby (Mitzi Gaynor), and the ongoing gag here is that, what with Nico trying to elevate himself in society, Gabby’s table manners and speech let him down.

So with no cash forthcoming, what’s a gangster to do to pad out his exile? So Nico decides to steal the crown. And if there had been either a hint of the classic heist a la Grand Slam (1960) or Topkapi (1964) or its alternative, the totally inept thief, then we might have been onto something. But instead we’ve got much what we might expect from such a poor piece – not much. And in any case, the laffs are meant to come from another party, representing the king’s citizens, and led by Dr Panzer (George Coulouris) who wants the crown restored to its proper home. Two crooks chasing the same prize? What a crazy idea. But this works as well as the rest of the picture.

Thanks to Gabby’s principles, the crown goes in neither’s pockets. To make a buck, Nico and the king transform the latter’s villa into a casino with Gabby, now Mrs Nico, employed as the hat check girl.

Stanely Donen made three pictures in 1960 and then not another man for three years, which suggested he was a) working on too many projects at once and b) that break sure refreshed his cinematic skills. Just like Once More with Feeling he gets wrong virtually most of the directorial decisions, beginning with the accents and ending up with the storyline and characters you don’t care a button for, which wouldn’t have mattered if they could generate a laugh.

Yul Brynner followed this up with his iconic performance in The Magnificent Seven (1960) so perhaps he can be excused. This pretty much killed off the career of Mitzi Gaynor (South Pacific, 1958) – it was another three years till she appeared on screen again, and that was her final picture. It took Noel Coward (Bunny Lake Is Missing, 1965) four years to get another screen role.

Written by Harry Kurnitz (Once More with Feeling) from the Art Buchwald novel so I am assuming this was greenlit before the results of the previous Donen-Brynner teaming were known.

At least Charade revived Donen’s career.