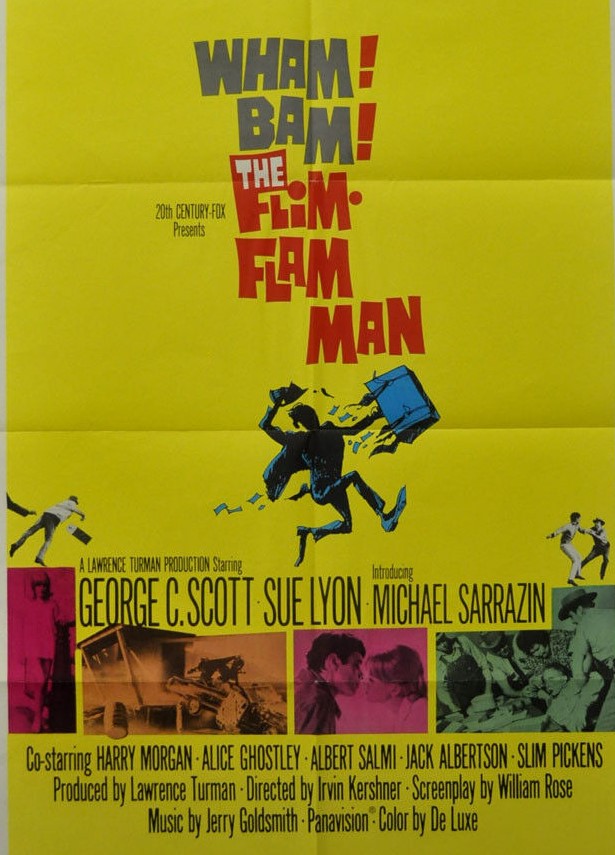

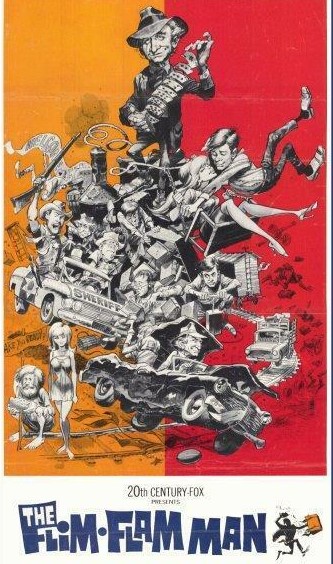

Throwback to It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963), prelude to Smokey and the Bandit (1977) and in the middle of the car chases and town wrecking a character study of a pair of grifters, one veteran, the other his pupil.

U.S. Army deserter Curley (Michael Sarrazin) teams up with veteran con man Mordecai (George C Scott) who teaches him the tricks of the trade. There’s nothing particularly innovative about the older man’s techniques – Find the Queen, The Lost Wallet, selling hooch as genuine whiskey – and the rewards are not particularly rewarding unless you are living at scavenger level in whatever run-down habitat you can find.

The dumb cops, Sheriff Slade (Harry Morgan) and Deputy Meshaw (Albert Salmi), aren’t quite so stupid otherwise they wouldn’t occasionally happen upon their quarry. And the larcenous duo offer nothing more clever by way of escape except to hijack vehicles.

So once you get past the aforementioned car chases and town wrecking it settles down into a gentle old-fashioned drama. Luckily all the good ol’ boy shenanigans are limited to the police, and neither main character is afflicted by over-emphatic accents.

Mordecai ain’t no Robin Hood nor a criminal mastermind who might have his eyes on a big- money heist. His ethos is stealing not so much from the gullible but the greedy. All his suckers think they can make an easy killing from a guy who appears a harmless old duffer.

He’s not looking for a big score because he’s got nobody to settle down with and because, although on a wanted list (as “The Flim-Flam Man” of local legend) he’s not going to exercise the authorities except cops with very little otherwise to do. He is as laid-back a drifter as they come.

Curley offers the drama. He starts to have qualms not so much about stealing from the greedy but about the repair bills for the cars they wrecked, especially one belonging to the young innocent Bonnie Lee (Sue Lyon), to whom he takes a fancy. While she reciprocates it’s only up to a point, having the good sense not to hook up with a criminal, so eventually he has to choose between giving himself up and serving time in the hope Bonnie Lee will hang around and severing his links with Mordecai, whom he treats as a father figure.

How he works that out is probably the best scene, especially given his temporary profession. Whether this is the first picture to feature so prominently incompetent cops rather than either the tough or corrupt kind I’m not sure but Slade and Meshaw take some beating.

In his first starring role, Michael Sarrazin (Eye of the Cat, 1969) is the cinematic catch. All the more so because director Irvin Kershner doesn’t take the easy route of focusing on his soulful eyes, permitting the actor to deliver a more rounded performance. He’s certainly more natural here than any future movie where he clearly relied far more on the aforementioned soulful eyes.

While I’m not sure the ageing make-up does much for him, George C. Scott (Petulia, 1968), in his first top-billed role, tones down the usual operatics and makes a convincing loner who can make one good romantic memory last a lifetime. He switches between completely relaxed to, on spotting a likely victim, sharp as a tack. The harmless old man guise falls away once he smells greed, replaced by cunning small-time ruthlessness.

Sue Lyon (Night of the Iguana, 1964) has little to do except not be the sex-pot of her usual screen incarnation and that’s to the good of the picture. By this stage of his career Harry Morgan was more likely to be found in television so it’s a treat to see him make the most of a meaty supporting part. Look out for Strother Martin (Cool Hand Luke, 1967) and Slim Pickens (Rough Night in Jericho, 1967).

Irvin Kershner (A Fine Madness, 1966) appears on firmer ground with the drama than the wild car chase/town wrecking but I suspect it takes more skills to pull off the latter than the former where the actors can help you out. Though I notice Yakima Canutt is down as second unit director so he might be due more of the credit. Screenwriter William Rose had already plundered the greed theme and, to that extent the car chase, for his seminal It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World.

The outlandish elements, fun though they are, give this an uneven quality that gets in the way of a tidy little picture.