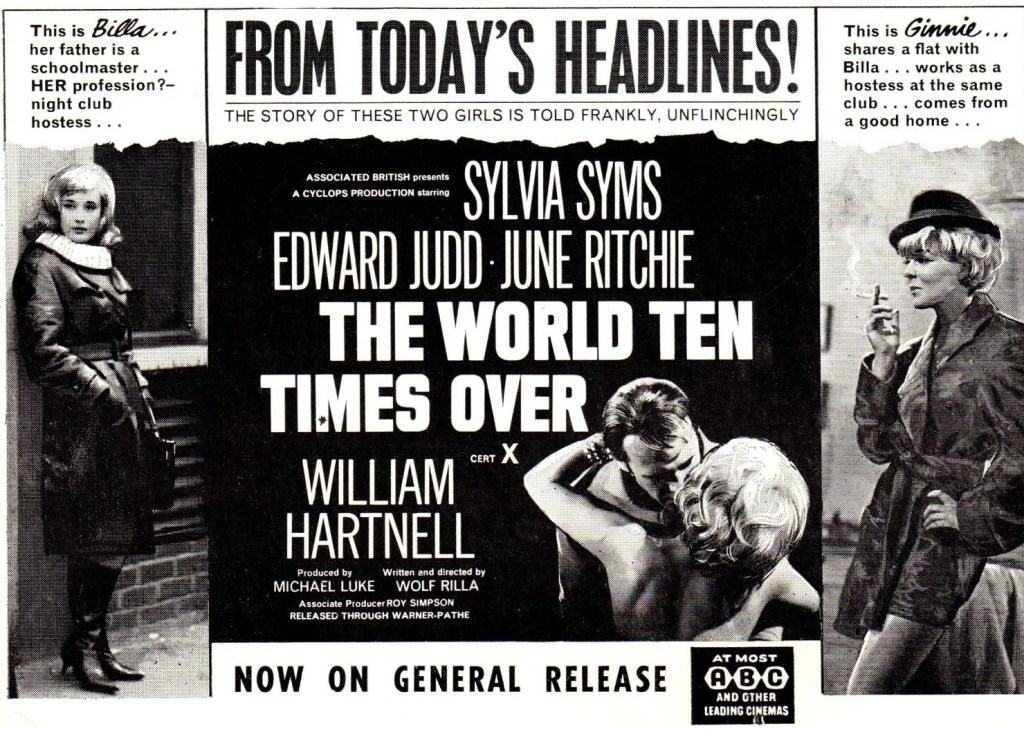

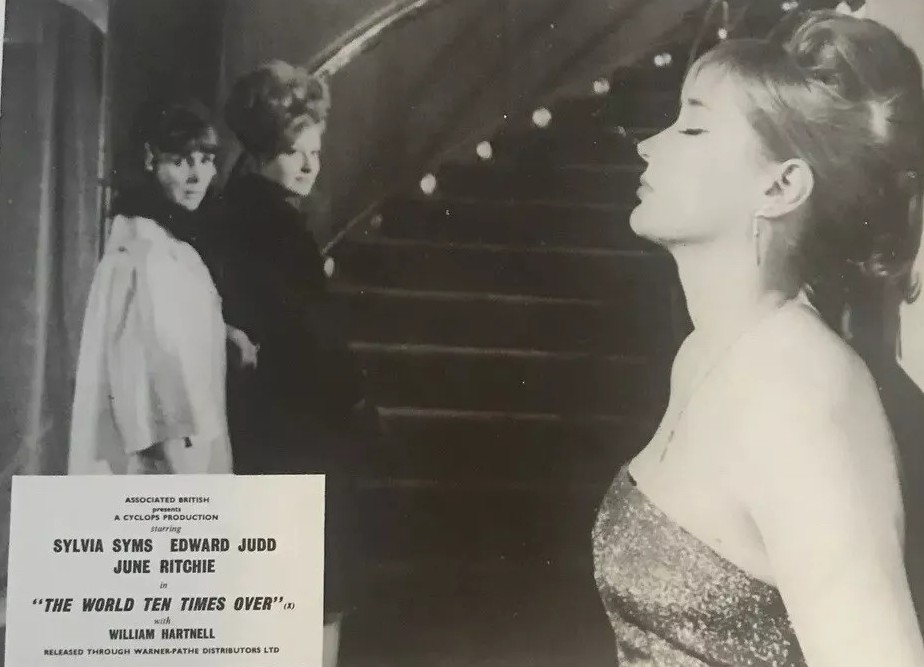

Sold as sexploitation fare, this is more of a chamber piece as flatmates Billa (Sylvia Syms) and Ginnie (June Ritchie) face up to crises in their lives. For two-thirds of the picture we steer clear of their place of occupation, a Soho nighclub, and only go there for a scene of unsurpassed male humiliation. Unusually, since the expectation would be that the two girls, supplementing their official income with some part-time sex working (implicit rather than explicit), would be treated as victims of wealthy males, in reality they serve up several plates of juicy revenge, but in accordance with their characters rather than as noir femme fatales.

In a very drab London, shorn of tourist hallmarks and red buses and royal insignia, Ginnie sets the tone, furious at lover Bob (Edward Judd), pampered son of a wealthy industrialist, for bringing mention of “love” into what she views as either (or both) an expression of pure pleasure or financial transaction. Bob is the old cliche, the client fallen in love with the girl. Attracted as she is by the pampering and the fact that she can twist him round her little finger, she values her independence too much to commit to such a weak man. In addition, she is so used to getting her way and so wilful that she delights in running rings around him, humiliating him in front of his entire office.

A contemporary picture like Anora (2024) would find space to excuse or explain her choice of employment, but here, beyond the fact that she left school aged 15 and has no qualifications, we are given nothing to work on, except that her predilection for doing exactly what she wants to do most of the time means she she might find steady employment a drain on her spritely personality.

Billa’s problem is she’s pregnant with no idea who the father might be and becomes infuriated by her widowed teacher father (William Hartnell) who can’t let go of his childlike notions of his beloved daughter. Thankfully, no notions of abuse, but just a dad not coming to terms with a grown-up daughter, shocked that she can knock back the whisky, and whose idea of a treat is taking her to one of the most difficult of the Shakespeare plays. Eventually, suspicions aroused, he tracks her down to the nightclub where she takes great delight in behaving disgracefully, refusing to leave at his presence, parental authority cut stone dead, the staff treating the father like any other punter, even setting him up with a girl (though on the house and he doesn’t take them up on the offer).

Meanwhile, the over-entitled Bob, failing to get his father to offer Ginnie a job except as an escort for the company’s clients, decides to leave his wife, books plane tickets for an exotic holiday only to be spurned. Ginnie recognizes more easily than him what a disaster marriage would be. She enjoys the fancy restaurants and fast cars but draws the line at commitment. She’s at her best when prancing around, indulging her whims, and yet there is a price to pay for her lifestyle as we discover in more sober fashion at the end.

Billa is sober pretty much all the way through, thoughtful, withdrawn, unable to connect with her father, her biggest emotional support being Ginnie. Despite her failure to go along with her father’s vision of her as an innocent child, her apartment is bedecked with childish paraphernalia, teddy bears, dolls etc.

Not quite a harder-nosed version of Of Human Bondage, and not far off as far as the males are concerned, but more of a character study of the two women.

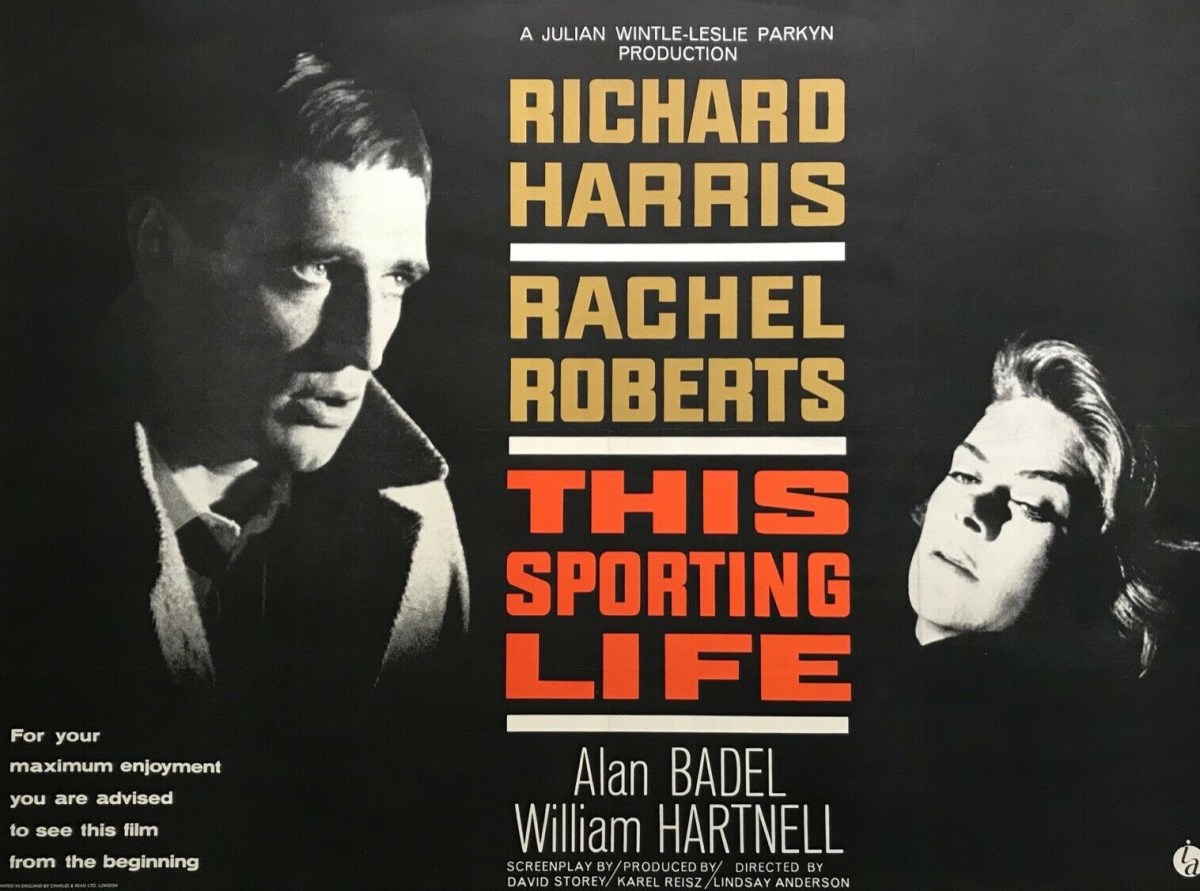

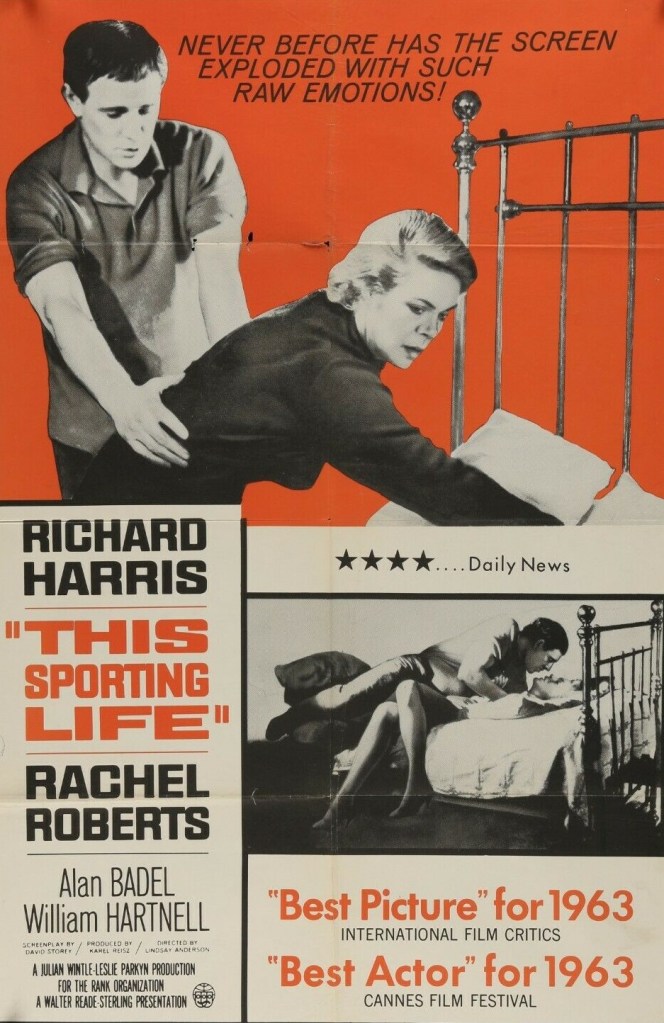

Although she has the less showy part, Sylvia Syms is the peach here, and if you consider her portfolio from The World of Suzie Wong (1960) through to East of Sudan (1964) this shows the actress at the peak of her ability. June Ritchie (A Kind of Loving, 1962) is excellent as the flighty piece and Edward Judd (The Day the Earth Caught Fire, 1961) steps away from his normal more heroic screen persona. This was William Hartnell’s last movie before embarking on his time travels for Doctor Who and it’s a moving portrait of an old man whose illusions are shattered.

Directed by Wolf Rilla (Village of the Damned, 1960) from his own screenplay.

Low-life never looked so glam and so shoddy at the same time.