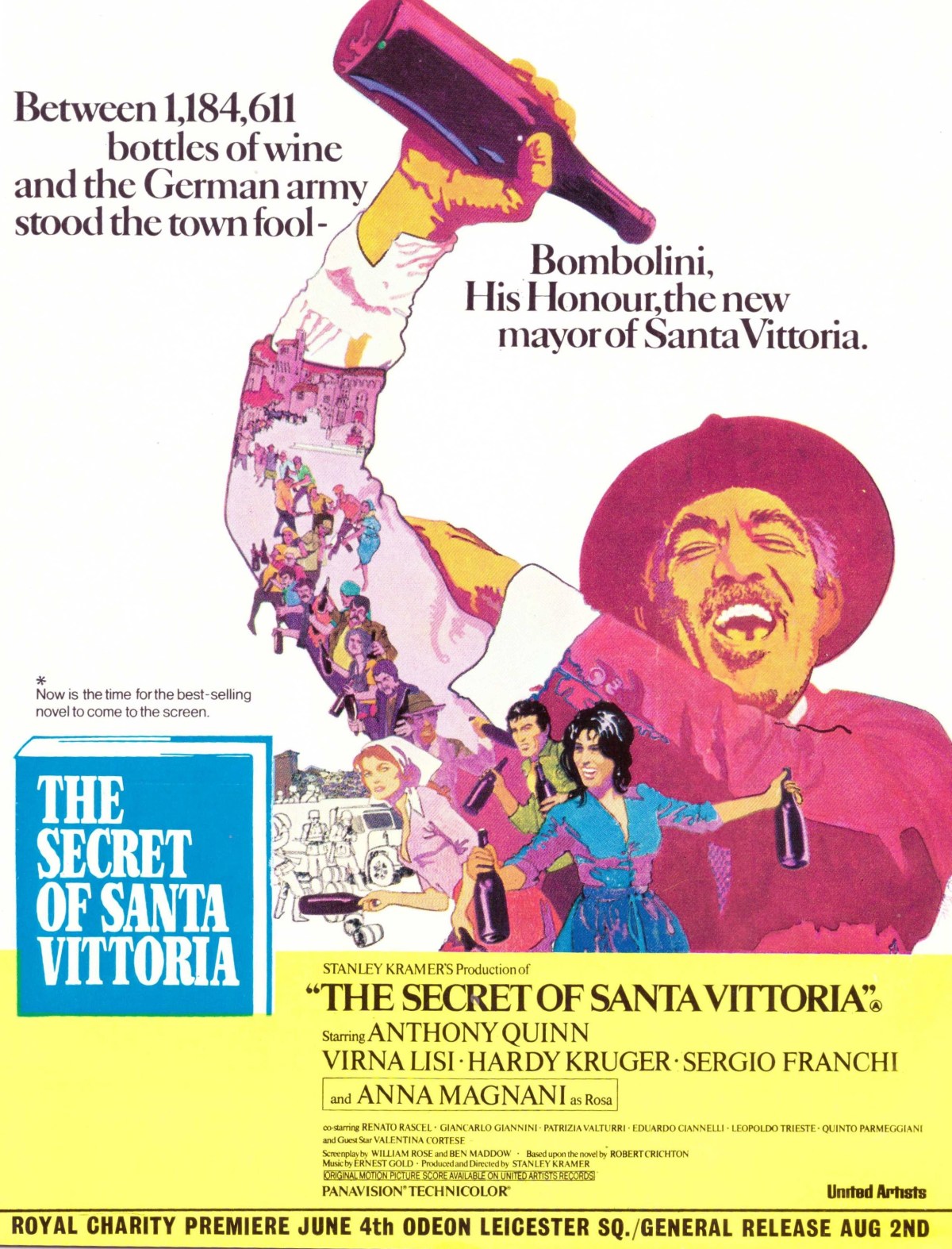

Sounds like a treasure hunt picture, contemporary buccaneers or thieves in search of missing gold. But there’s nothing in the way of maps waiting to be discovered, no clues, no character unhinged by its pursuit. In fact, the valuable commodity here is wine, over a million bottles of it. Everyone in the hilltop town of Santa Vittoria is in on the secret. Because they hid it from prying Germans who have taken over the place after the death of Italian dictator Mussolini. And that element of the story, once we finally embark on it, doesn’t begin until halfway through.

Meanwhile, we are treated to the browbeaten drunk Bombolini (Anthony Quinn), too dumb to realize that being elected mayor – the previous incumbent kicked out for being a Fascist – is a poisoned chalice. However, taking a few tips from Machiavelli he works out that his survival depends on bringing together a council of more sensible heads. His new position cuts no ice with disgruntled wife Rosa (Anna Magnani) whose weapons of choice, vicious tongue apart, include copper pans and an elongated rolling pin.

But if you were desperate to know how to bury treasure, here’s your chance. A good quarter of an hour is spent on that element. I’m not entirely sure what fascinated director Stanley Kramer (Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, 1967) about this. Because, clever though the scheme is of vanishing into thin air more than a million bottles, it takes little more than lining up the populace in rows close enough together so they can pass a bottle onto their neighbor, until the total amount – minus 300,000 bottles left behind to fool the Germans – is hidden in tunnels in the caves below the village.

Assuming of course the Germans fail to prod the stones concealing the tunnels and discover the cement is too fresh to be ancient. But Bombolini is in luck because German leader Captain von Prum is a “good German,” inclined to take things easy, coming down hard of any of his soldiers who pester female villagers, allowing the mayor to negotiate to retain some of the supply being handed over to the invaders, half his mind on the local Countess Caterina (Virna Lisi) with whom he fancies his chances, but in gentlemanly fashion of course, aiming to seduce her over dinner rather than resorting to force.

That matter is complicates because the widowed countess already has a lover, a wounded soldier Tufa (Sergio Franchi) whom she nursed. It’s only when the captain realizes that he has been duped by the apparent buffoon of a mayor and by the countess that things start ugly and soon you can hear cries of the torture echoing out over the piazza.

The odd mixture of comedy and reality fails to gel. Anna Magnani (The Fugitive Kind, 1960) doesn’t look as if she’s acting in showing her distaste of Anthony Quinn (Lost Command, 1966) possibly because he is over-acting, cowing and whimpering and using his hands to express every single word he speaks. But it looks authentic enough. Either Kramer has rounded up every aged extra left over from Once Upon a Time in the West (1969) or he has recruited scores of ordinary peasants to play the villagers.

Kramer’s usual earnestness has disappeared, and although his first movie was a comedy, and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, his previous picture, played on the comedic elements of the situation, his feeling for comedy is rusty at best, non-existent at worst. It’s hard to feel any particular sympathy, as would be the point, in the villagers outwitting the Germans and in the fact that they have changed from ostensible World War Two conquerors to the conquered once their erstwhile allies turned on them.

You might consider this a feminist twist on The Taming of the Shrew, Rosa not only being a shrew who would never be tamed, not even by Germans, but actually the family breadwinner. While, until his election, her husband is a nonentity. And it might be viewed as a choice role for Anthony Quinn, a dramatic shift away from the heroic roles with which he was more often associated. Anna Magnani mostly looks as if wondering why she agreed to participate.

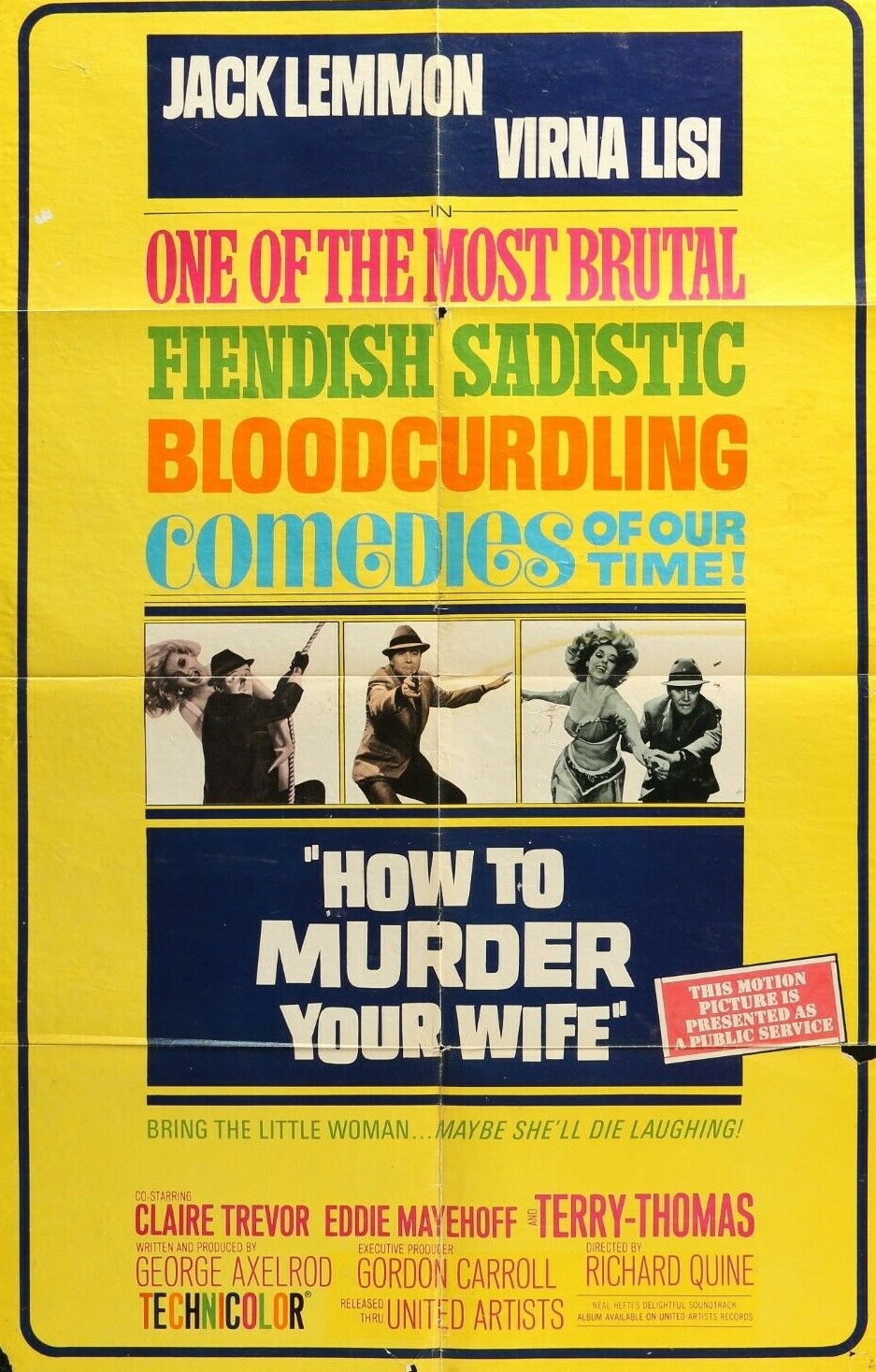

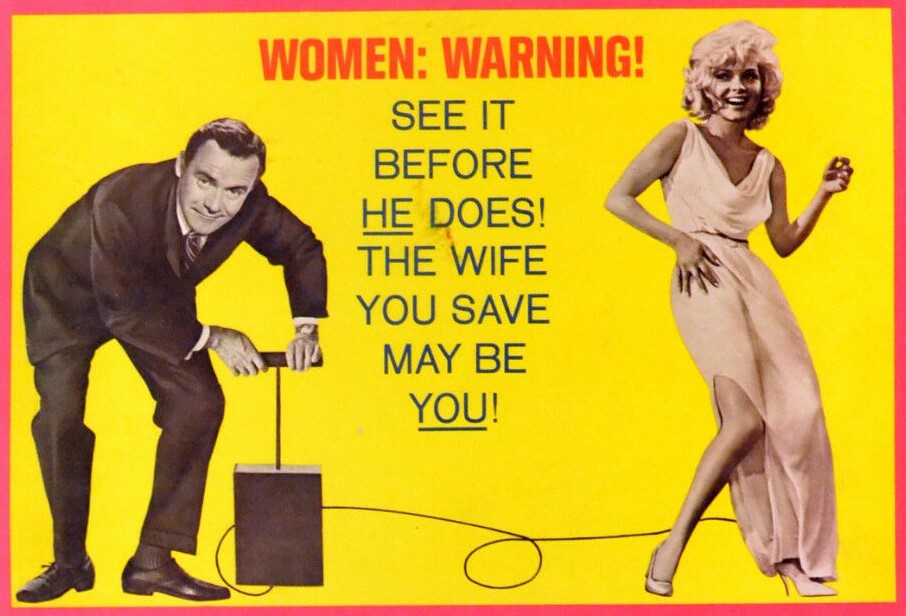

The best acting comes from Virna Lisi (How to Murder Your Wife, 1965), a widow realistic about the lack of true love in what sounds like an arranged marriage, and faced with having to keep the amorous captain sweet, and possibly doing whatever that takes in order to protect the townspeople. Hardy Kruger (The Red Tent, 1969) has also abandoned his normal arrogance, is uncomfortable with being a despot, wanting to maintain friendly relations with the villagers, and seeking solace in gentlemanly fashion from the countess. He has the best scenes, the look of superiority as he outwits, he thinks, Bombolini, and the look on horror on his face as he discovers the countess’s lover.

Based on the bestseller by Robert Crichton with a screenplay by William Rose (Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner) and Ben Maddow (The Way West, 1967) it’s the kind of movie that raises a lot of questions without bothering to answer any of them.