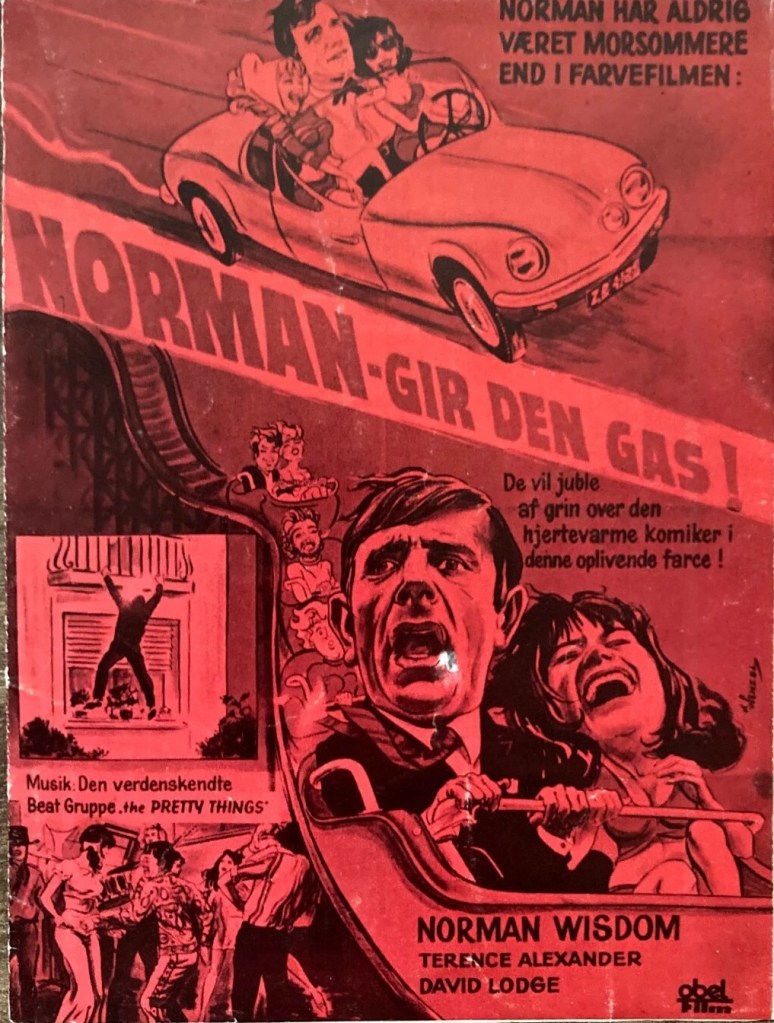

One of those comedies that works best in a time capsule and far more interesting for the coincidences and anomalies of those involved. What are the chances, you might ask, of sisters playing roughly the same role in two entirely different movies, one a comedy the other a drama, in the same year. We’ve got Sally Geeson here, in her debut, playing a free loving hitchhiker picking up an older married man and we’ve got her slightly more experienced sister Judy Geeson (Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush) as a free loving hitchhiker picking up older married man Rod Steiger in Peter Hall’s Three into Two Won’t Go (1969).

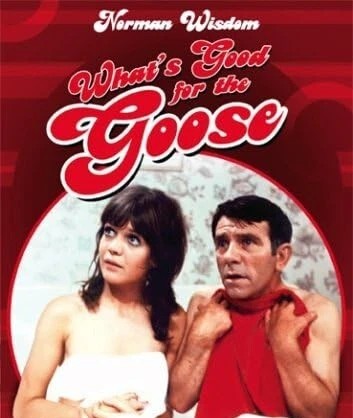

This proved the final starring role for Norman Wisdom (A Stitch in Time, 1963), at one time a huge British box office star, who had been infected by that disease that seems to always hit comedians, of wanting to play it straight. While there is some comedy, it’s sorely lacking in the kind of physical comedy, the pratfalls and such, with which Wisdom made his name.

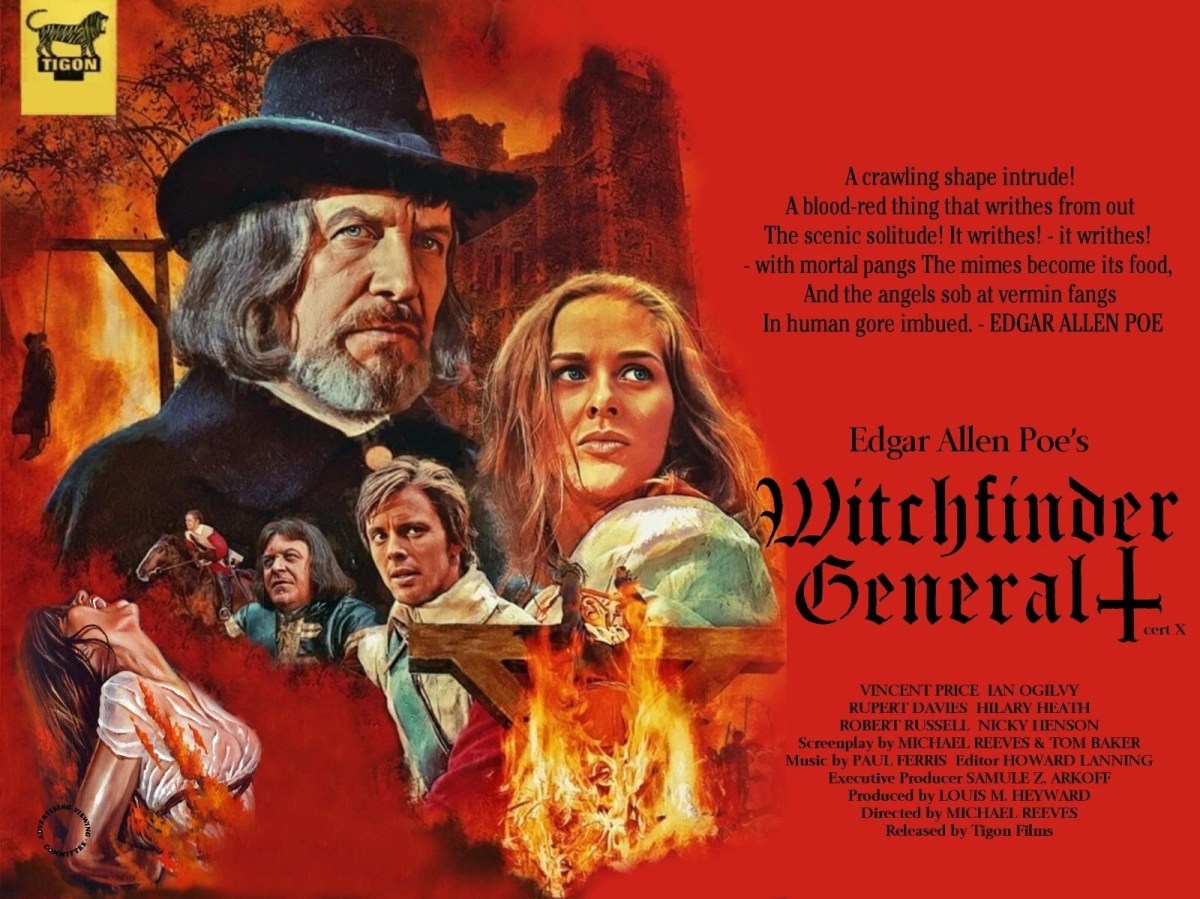

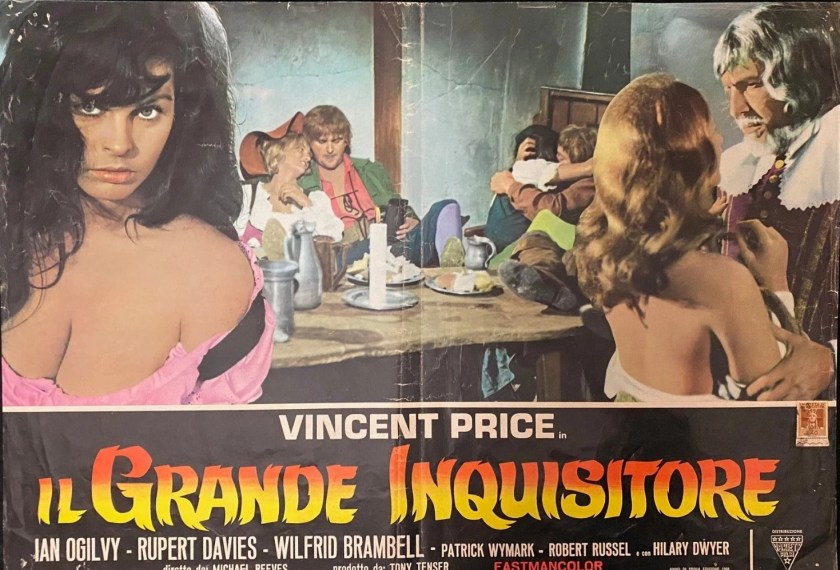

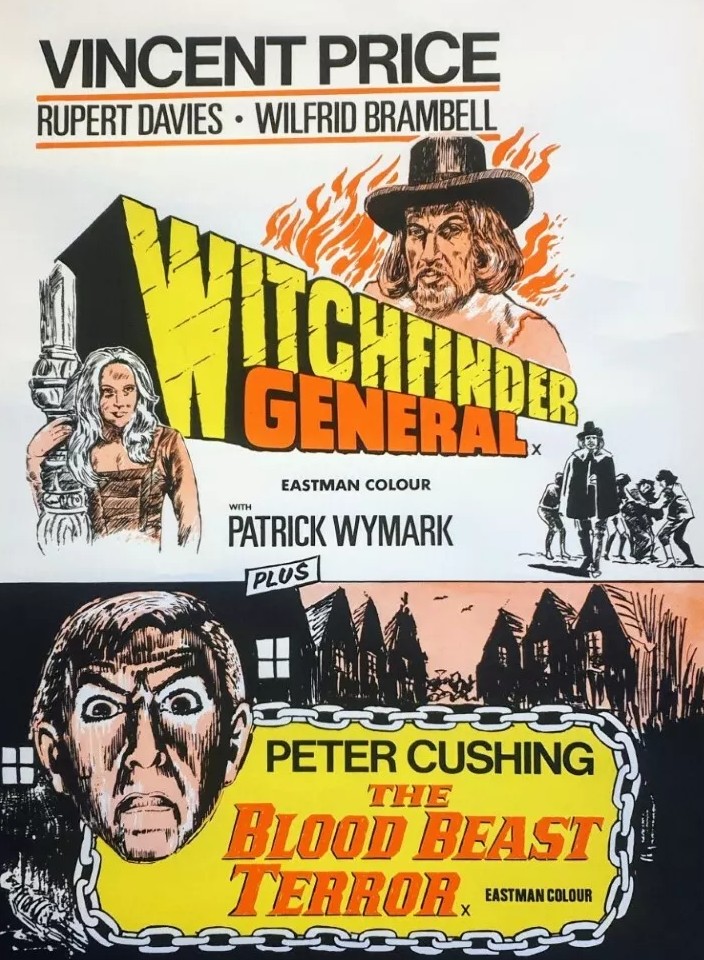

And there’s another name to conjure with – Menahem Golan. More famous, eventually, for foisting on the general public a string of stinkers under the Cannon umbrella and taking over the British cinema chain ABC before going spectacularly bust. What’s his role in all this? He’s the creative force, would you believe, wearing his writer-director shingle, in his first movie outside Israel. And if that’s not enough, the producer is Tony Tenser, also trying to change direction, switching from the horror portfolio which with his outfit Tigon had made its name and into a different genre.

And if you want another name slipped in, what about Karl Lanchbury, playing a nice guy in contrast to the creepy characters he tended to essay in the likes of Whirlpool / She Died with Her Boots On (1969).

Time capsule firmly in place we’re in a Swinging Britain world where young girls listen to loud rock music (though don’t take drugs) and go where the mood takes them, free travel easily available through the simple device of hitchhiking.

Timothy Bartlett (Norman Wisdom) is a bored under-manager drowning in a sea of bureaucracy and turned off by wife Margaret (Sally Bazely) who goes to bed wearing a face mask and with her hair in curlers. On the way to a business conference he picks up two hitchhikers, Nikki (Sally Geeson) and Meg (Sarah Atkinson), becoming smitten with the former, making hay at a night club where his “dad dancing” is the hit of the evening. He slips into the counterculture, wearing hippie clothes, generally unwinding, doing his thing, and sharing his bed with Nikki.

You can tell he’s going to get a nasty shock and just to put that section off we dip into a completely different, almost “Carry On” scenario, where his efforts to sneak Nikki in his bedroom are almost foiled by an officious receptionist. Eventually, she invites all her hippie pals to make hay in his hotel room while she makes out with Pete (Karl Lanchbury),a man her own age, and Timothy is told in no uncertain terms the essence of free love is that she doesn’t hang around with a man for long, in this case their affair only lasted two days.

It’s the twist in the tail that generally makes this work. Rather than moan his head off or believe he is now catnip to young ladies, Timothy, unshackled from convention, uses his newfound freedom to woo his wife.

So, mostly a gentle comedy, and good to see Norman Wisdom not constantly having to over-act and twist his face every which way but loose, even though this effectively ended his career. The teenagers enjoy their freedom without consequence (nobody’s pregnant or addicted to drugs) and there’s a fairly good stab at digging into the effortless joys of the period. Sally Geeson (Cry of the Banshee, 1970) didn’t prove as big a find as her sister and her career fizzled out within a few years.

As an antidote to the Carry On epidemic, this works very well.

A gentle comedy.

You can catch this on YouTube courtesy of Flick Attack.