Admit it, you always wanted to discover what went on behind Peter Cushing’s chilly British reserve. The man who appeared to be constantly tormenting that nice Dracula or donning a deerstalker to outwit countless villains or battling otherworldly creatures like the Daleks or just a dependable character who in the unconventional Sixties knew right from wrong.

Of course, our Peter had occasionally come unstuck, the duped bank manager in Cash on Demand (1961) but even as Baron Frankenstein he never revealed a demonic side even as he created monsters who had a tendency to run wild, always civil to the last, stiff upper lip never quavering.

So it’s something of a surprise to see him cast in the first place as the older man lusting after a younger woman. Sir John Rowan (Peter Cushing) is a highly esteemed surgeon who has fallen for model-cum-flighty-piece Lynn (Sue Lloyd) and although he sticks out like a sore thumb at a typical Swinging Sixties party full of gyrating lithe young women he is happy to put up with it for the sake of his girlfriend.

But Lynn has a strong independent streak, she’s not the submissive lass who might have been content to swoon at the feet of such a highly intelligent man, and objects to his attempts at control and can’t resist the chance to show her allure to all and sundry by giving in to the temptation to pose for louche photographer Mike (Anthony Booth), and, as it happens, the assembled throng.

Sir John isn’t going to stand for such brazenness, starting a fight with Mike that ends in a dreadful accident, destroying half Lynn’s face. Naturally, plastic surgery being the coming thing and Sir John capable of turning his hand to anything he’s able to fix up her face good and proper.

Except it’s a temporary measure, something to do with the pituitary gland, and it turns Sir John into a serial killer. There’s no mystery to it, no detective scouting around trying to put together clues, the question soon becomes can Sir John keep it up and what psychological damage is inflicted on Lynn as she comes to the realization that the beauty she had taken for granted, setting aside the predations of age which are still some way off, could vanish in an instant leaving her shrieking in a mirror.

Things get out of hand when they head for the country and fresh victims and find themselves trapped in a home invasion by a gang as gormless and vindictive as the pair from The Penthouse. It doesn’t end the way you’d expect because there’s a twist in the tail that you might accept as par for the course in the unconventional cinematic Sixties or you might just put the producers down for wanting to have their cake and eat it.

Still, it’s good while it lasts. Cushing certainly reveals a different side to his screen persona, and I can’t remember ever seeing him truly in love or indulging in a passionate screen kiss, and certainly to see his murderous side emerge is quite a treat, no scientific excuse to mask his behavior.

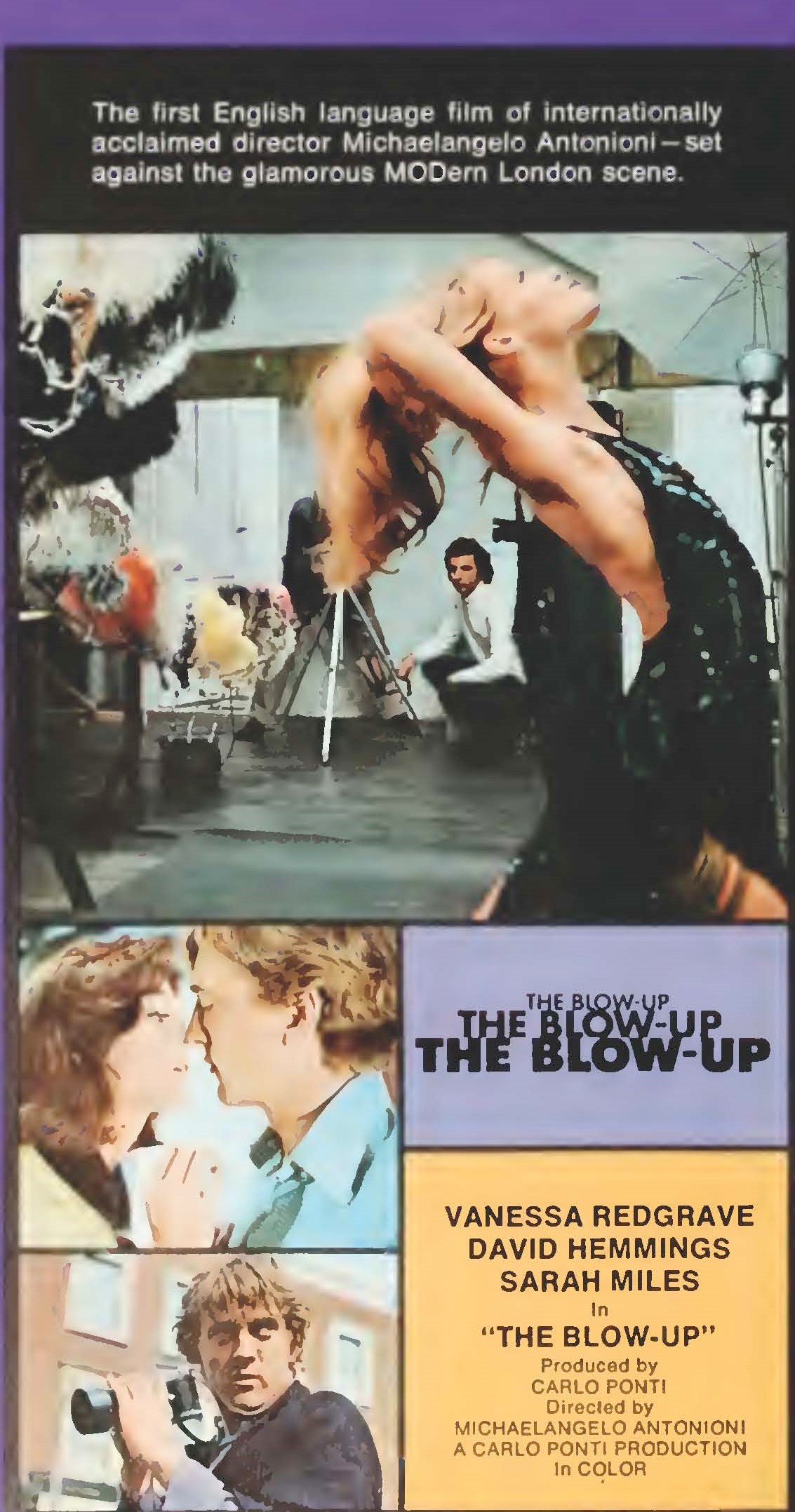

And it’s equally good to see Sue Lloyd (The Ipcress File, 1965) in another of those roles where she displayed considerable independence. As an added bonus future Hammer Queen Kate O’Mara (The Horror of Frankenstein, 1970), here cleavage well hidden, turns up as Lynn’s sister. You might also spot Vanessa Howard (Some Girls Do, 1969) and Marianne Morris (Vampyres, 1974). Anthony Booth (Girl with a Pistol, 1968) was trying to shake off the shackles of BBC comedy Till Death Us Do Part

Robert Hartford-Davis (The Black Torment, 1964) does pretty well unsheathing the beast within the context of a vulnerable older man. Derek Ford wrote the screenplay with his brother Donald before he decided the sex film was his way to British film legend. The version released abroad contains more gore and sex than when the British censor had its wicked way.