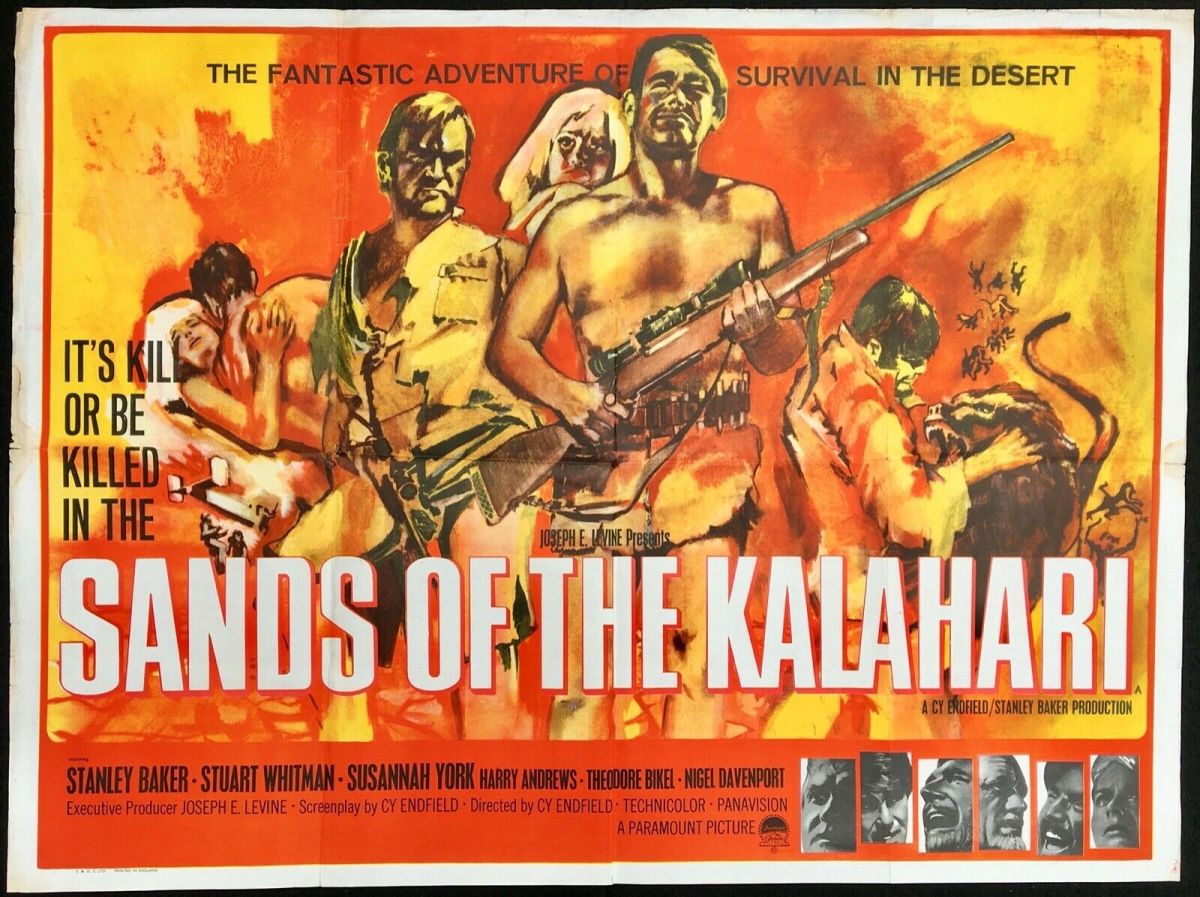

You know the score: plane crashes in inhospitable territory (in this case a desert), personalities clash as food/water is rationed, tempers run high and/or depression sets in as attempts to attract attention fail, someone goes for help, someone else has an ingenious idea and eventually everyone rallies round in common cause. That template worked fine in The Flight of the Phoenix (1965).

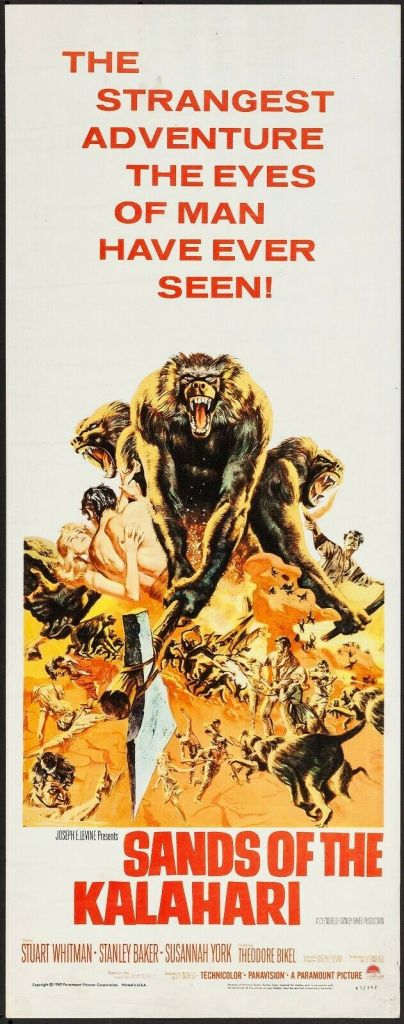

It doesn’t here. This is not quite as inhospitable. There is water. Caves offer shelter from the blazing sun. There is food – lizards trapped, game hunted with telescopic rifle. But the food is lean, not fattened through farming for human consumption. And you have to watch out for marauding baboons not to mention scorpions. And this group is split, two alpha males intent on exerting dominance with little interest in common cause.

without close examination of the picture’s content.

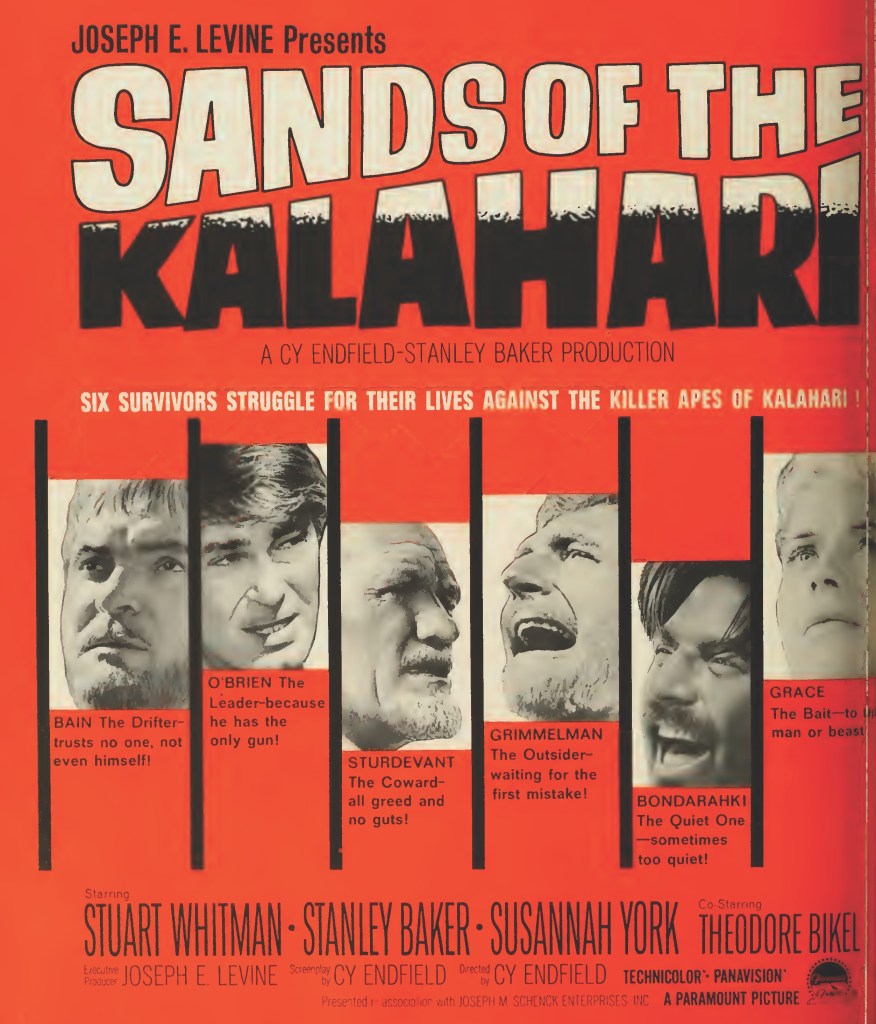

Of the six survivors of this crash, Sturdevan (Nigel Davenport) decides his leadership status entitles him to sole claim over the only woman, Grace (Susannah York). But when he accepts the genuine responsibilities of leadership, he sets off across the desert to get help. That leaves Grace to fall into the hands of O’Brien (Stuart Whitman), so alpha he could be auditioning for Tarzan, shirt off all the time.

It soon transpires O’Brien has a rather unusual idea of survival – getting rid of his companions so that he will have no shortage of food until rescue arrives. It takes a while for the others to catch on to his plan. And then rather than common cause and camaraderie, it becomes every man/woman for himself, a battle for individual survival, a return to the primeval.

The most likely challenger to O’Brien’s authority is Bain (Stanley Baker), but he has been badly injured in the crash and no match for the other man’s brawn or his weapon. So it becomes a game of cat and mouse. Except it’s in the desert, it’s the law of the jungle and the rule of autocracy brought home with sudden force to people accustomed to the comforts of civilization and democracy.

The movie’s structure initially takes us down the obvious route of common purpose – Grimmelman (Harry Andrews) knows enough survival lore to devise a method of water transportation that would permit the group to escape the desert, Dr Bondrachai (Theodore Bikel) formulates a method of trapping lizards, and O’Brien, at least at first, appears willing to take on the role of protector, warding off baboons with his gun.

The change into something different is subtle. While the others are desperate to escape, it becomes apparent that O’Brien has found his metier. We discover little about the lives of each individual prior to being stranded. Whatever O’Brien’s standing in society, it would not have been as high as here, where his superior skills stand out. Reveling in his supremacy, he doesn’t particularly want to go home.

Like any psychopath Bain knows how to manipulate so at first it seems his decisions are for the greater good. And only gradually does it emerge that he blames others for his own mistakes and intends to eliminate his rivals for the food supply one by one. Because he is so handsome, it is impossible to believe he could be so devious or so evil.

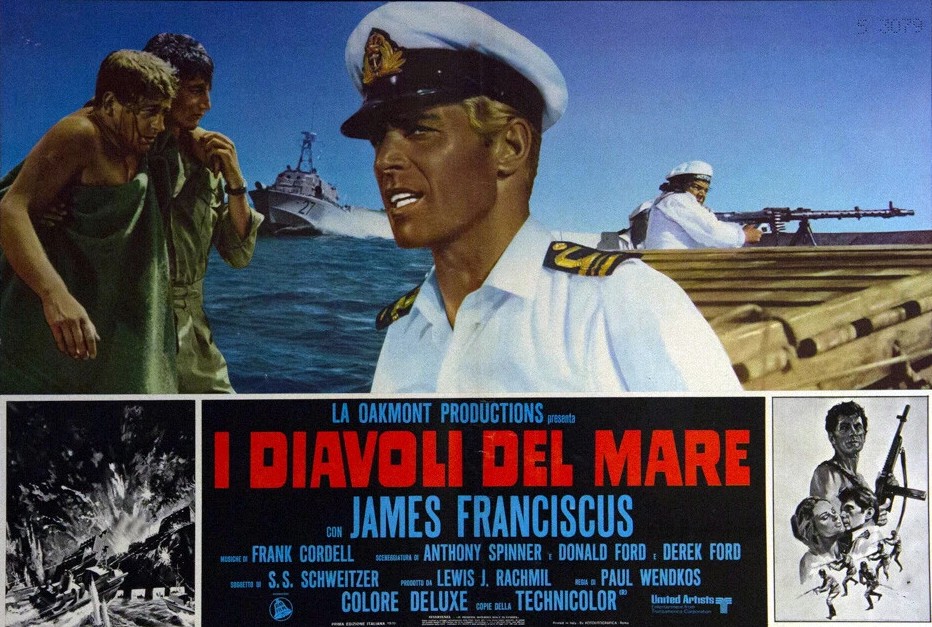

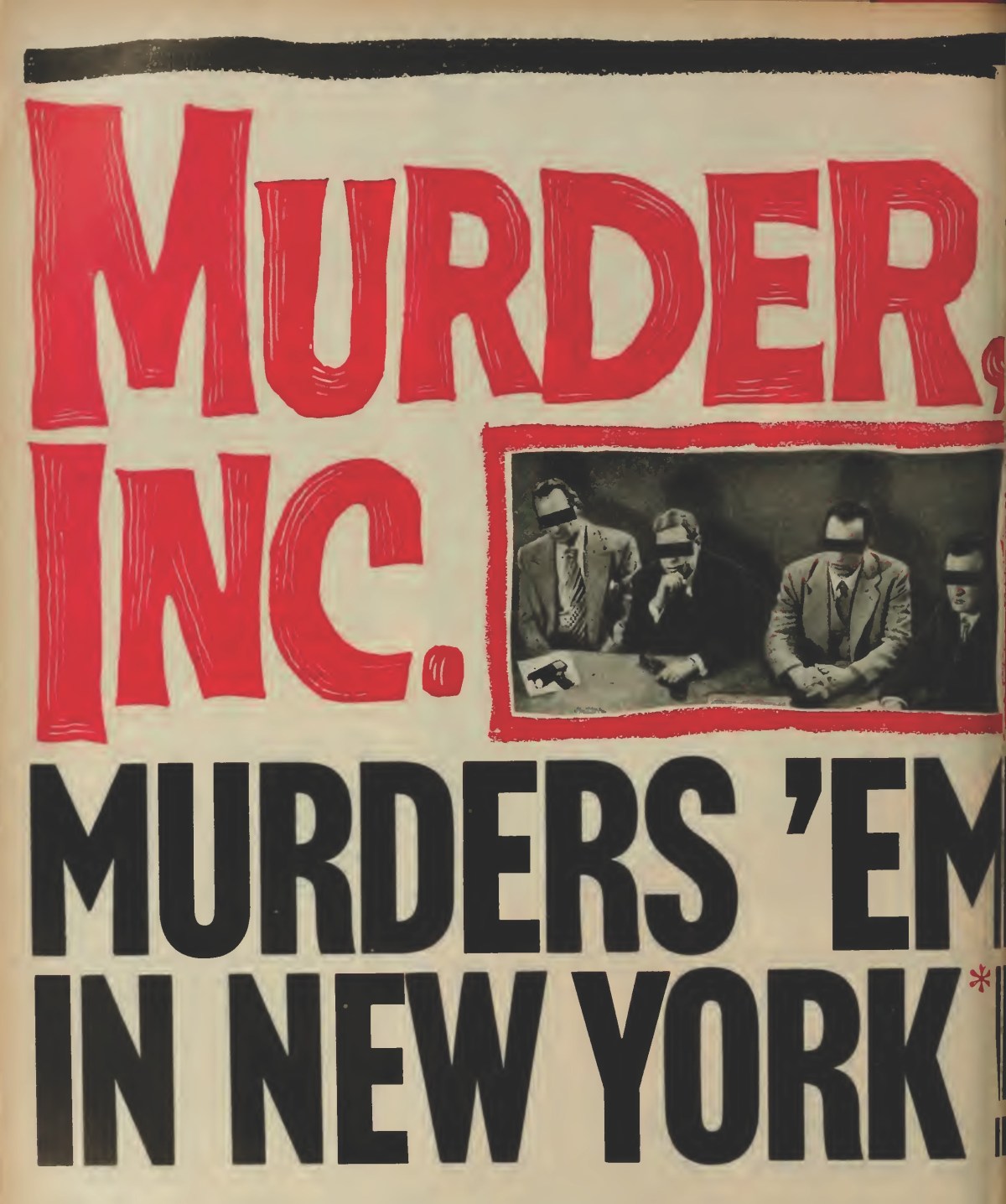

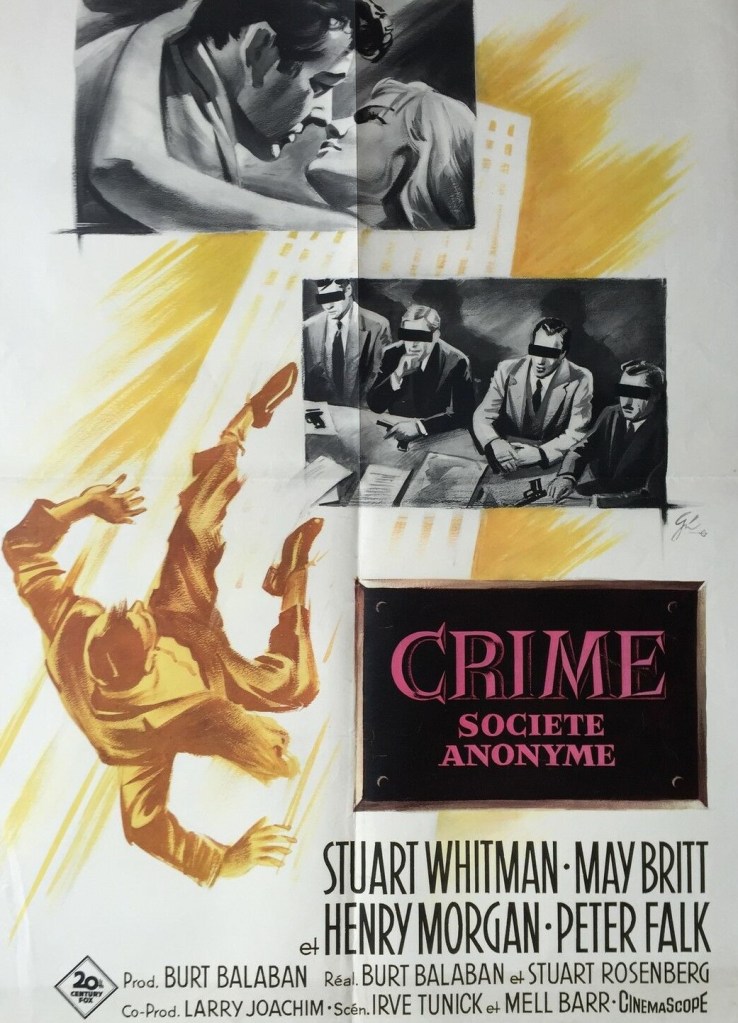

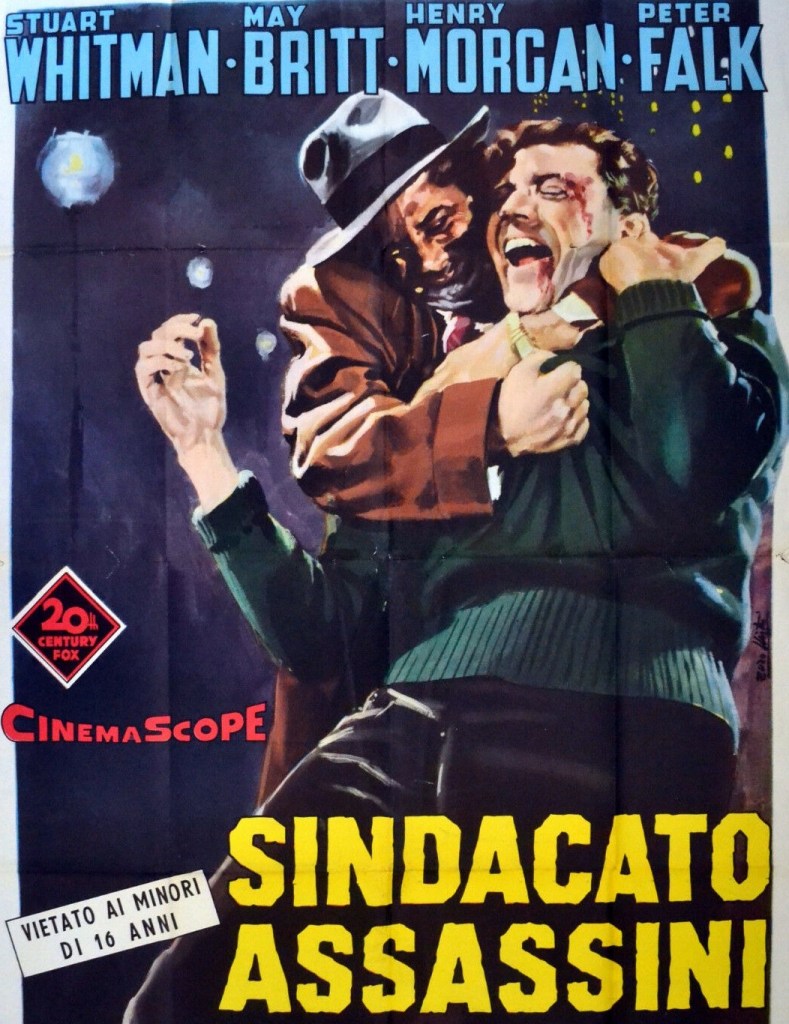

The three principals all play against type. Stanley Baker (Zulu, 1963) and Stuart Whitman (Murder Inc., 1960) made their names playing heroic types. Here Baker is too ill for most of the picture to do any good and Whitman plays a ruthless killer. But Susannah York (Sebastian, 1968) is the big revelation. Audiences accustomed to her playing glamorous, perhaps occasionally feisty, gals will hardly recognize this portrayal of a coward, not just abjectly surrendering to the alpha male but seeking him out for protection and guilty of betrayal.

Even though this picture is set in the days before gender equality and the independent woman was a rarity, Grace’s acquiescence to the powerful male is disturbing, in part because it takes us back to the days when a woman was impotent in the face of male dominance. Such is York’s acting skill that rather than despise this woman, she earns our sympathy.

While for the most part Harry Andrews (Danger Route, 1967) and Nigel Davenport (Sebastian, 1968) appear in their usual screen personas of strong males, here their characters both are changed by the circumstances. Theodore Bikel (A Dog of Flanders, 1960) has the most interesting supporting role, the only one who takes delight in the adventure.

Director Cy Endfield (Zulu) – who also wrote the screenplay based on the William Mulvehill novel – delivers a spare picture. There is virtually no music, just image. Aerial shots show tiny figures in a landscape. The absence of character background frames the story in the present. As a reflection on the animal instinct, how close to the primordial a human being still operates, no matter how enlightened, this works exceptionally well, and melds allegory with thriller.