If ever a film deserves reassessment, this is it. This western, marketed as a vehicle for Burt Lancaster in the wake of hugely successful The Professionals (1966), sees the star playing cussed trapper Joe Bass trying to retrieve furs stolen first by Native Americans and then by outlaws. That the serious race issues tackled here were dressed up in very broad comedy and typical western action ensured it missed out on the kind of recognition that critics would assign a straightforward drama and lost its rightful place as a pivotal picture of the decade.

In theory, a somewhat unusual Burt Lancaster western. In reality something else entirely. For large chunks of the movie Lancaster is absent as the story follows the fortunes of Black slave Joseph Lee (Ossie Davis) as he achieves not just freedom but genuine equality. Joseph is introduced as a slave of the Kiowa, left behind when the Indians steal Joe Bass’s furs. In compensation for his loss, Bass plans to sell Lee in the slave market in St Louis and in the meantime enrols him to help recover his furs.

However, a band of outlaws, specializing in collecting Native American scalps (hence the title) and selling them at $25 a time, get to the furs first as a by-product of a raid on the Kiowas. In pursuit with Bass, Lee falls into a river at the outlaw encampment and becomes the slave of Jim Howie (Telly Savalas) who also aims to sell him. Lee plans to escape until discovering Howie’s large troop is headed for Mexico where the slave would automatically become free. With clever talk, beauty-treatment skills and knowledge of astrology and ecology, Lee insinuates himself into the wagon of Howie’s paramour Kate (Shelley Winters).

With Bass still in pursuit, there are several excellent action scenes as the outnumbered trapper seeks to outwit Howie who turns out to be just as devious. But the main question is not whether Bass will recover his stolen property but which side will Lee pick. Will he act as spy to help Bass get back his furs or will he disown Bass and remain with the murderous genocidal gang who could provide a prospct of freedom? Either in the company of Bass or Howie, he is constantly reminded of his status, taking a beating from one of Howie’s thugs, Bass refusing to share his whisky because he views him not just as a slave who “picked his master” but as a coward refusing to fight back when attacked and beaten up.

The film comes to a very surprising ending but by that time through his own actions Lee is accepted as an equal by Bass and the issue of slavery dissolved. In effect, it is a tale of self-determination. Lee effects liberty by taking advantage of situations and standing up for his own cause.

Lee is one of the most interesting characters to appear on the western scene for a long time. Exactly where he acquired his education is unclear and equally hazy are how – and from where – he escaped and how he ended up as slave of the Commanches before they traded him to the Kiowa. However he came to be in the thick of the story, his tale is by far the most original. But he’s not the only original. The fearless Bass was an early ecological warrior with an intimate understanding of living off the wild, not in normal genre fashion of killing anything that moves, but in knowing how to find sustenance from plants. That in itself would endear him to modern lovers of alternative lifestyles.

Normally the derogatory term “scalphunters” would be reference to Native Americans, but here it is American Americans who exploit this market. Despite being the leader of a vicious bunch, Howie turns out to be a bit of a romantic and Kate a bit more interested in the world than your average female sidekick.

Director Sydney Pollack (The Slender Thread, 1965) does a marvelous job not just in fulfilling action expectations and taking widescreen advantage of the locations but in allowing Lee to take center stage when, technically, according to the credits, Ossie Davis was only the fourth most important member of the cast. Burt Lancaster was approaching an acting peak, following this with The Swimmer (1968) and Castle Keep (1969), happy to take risks on all three pictures, especially here where for most of the movie he is outwitted and ends up in a mud bath.

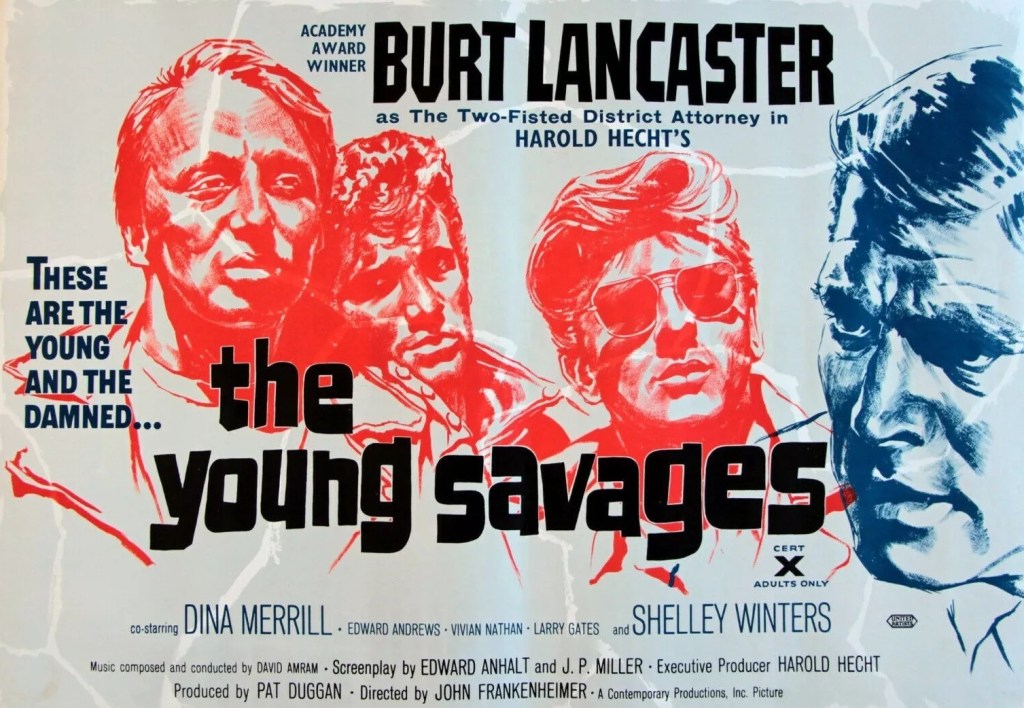

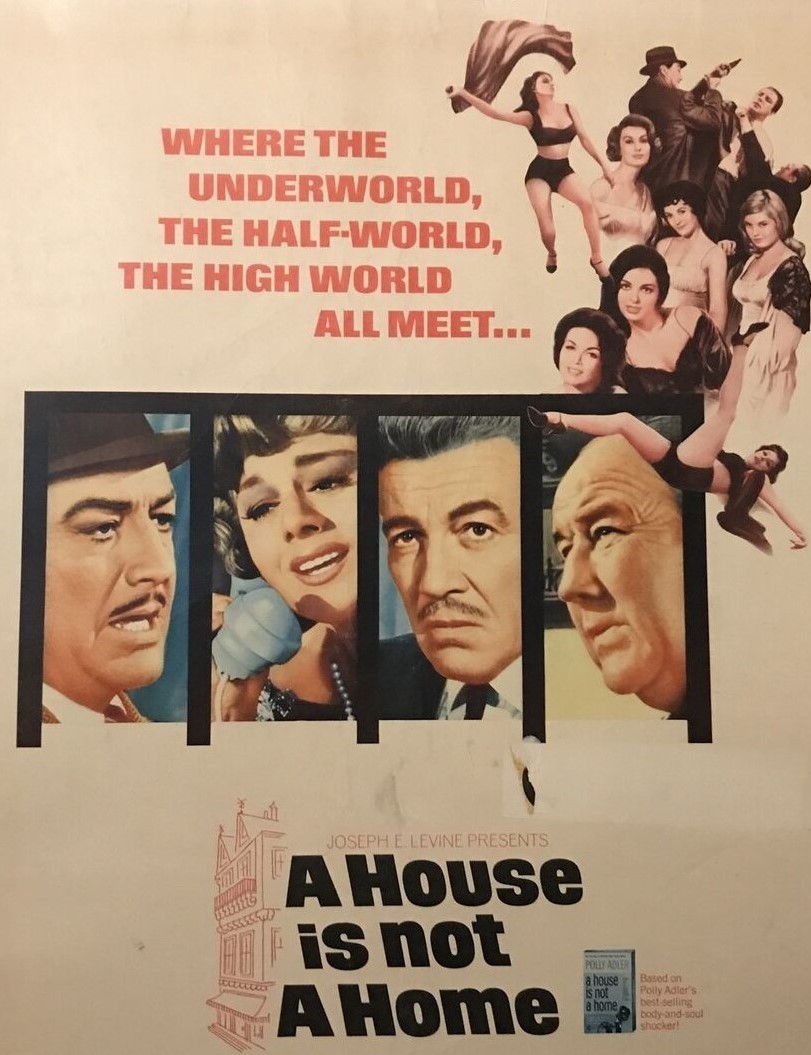

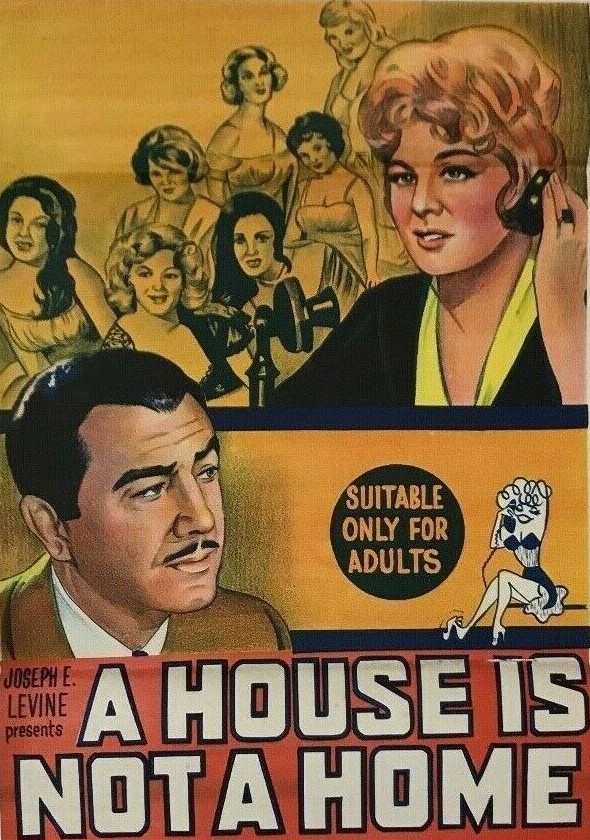

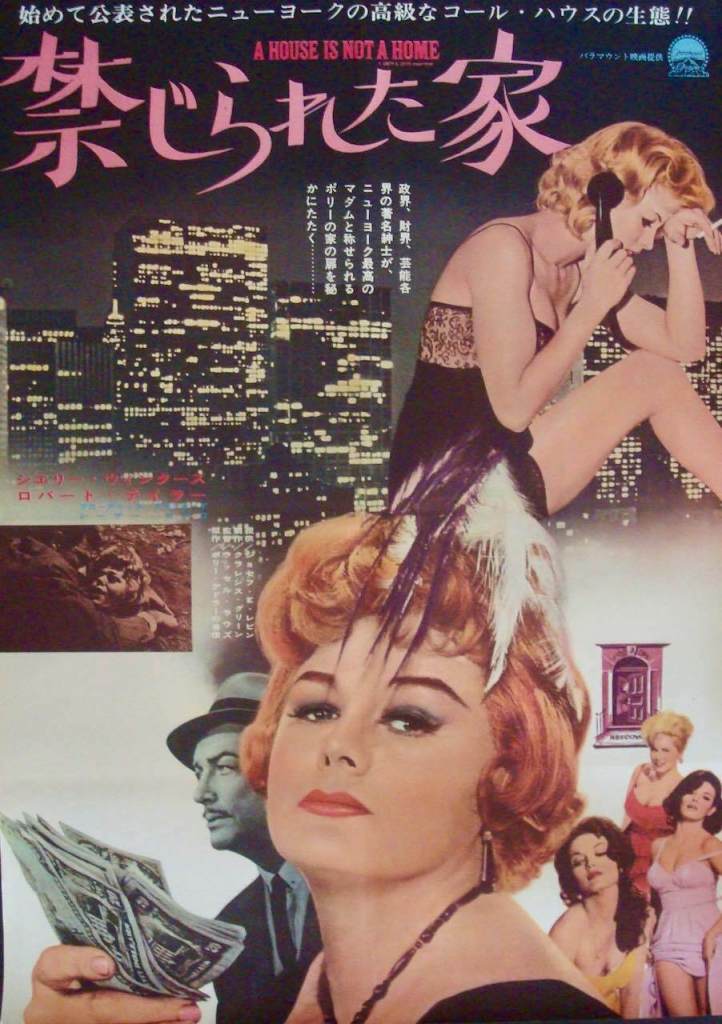

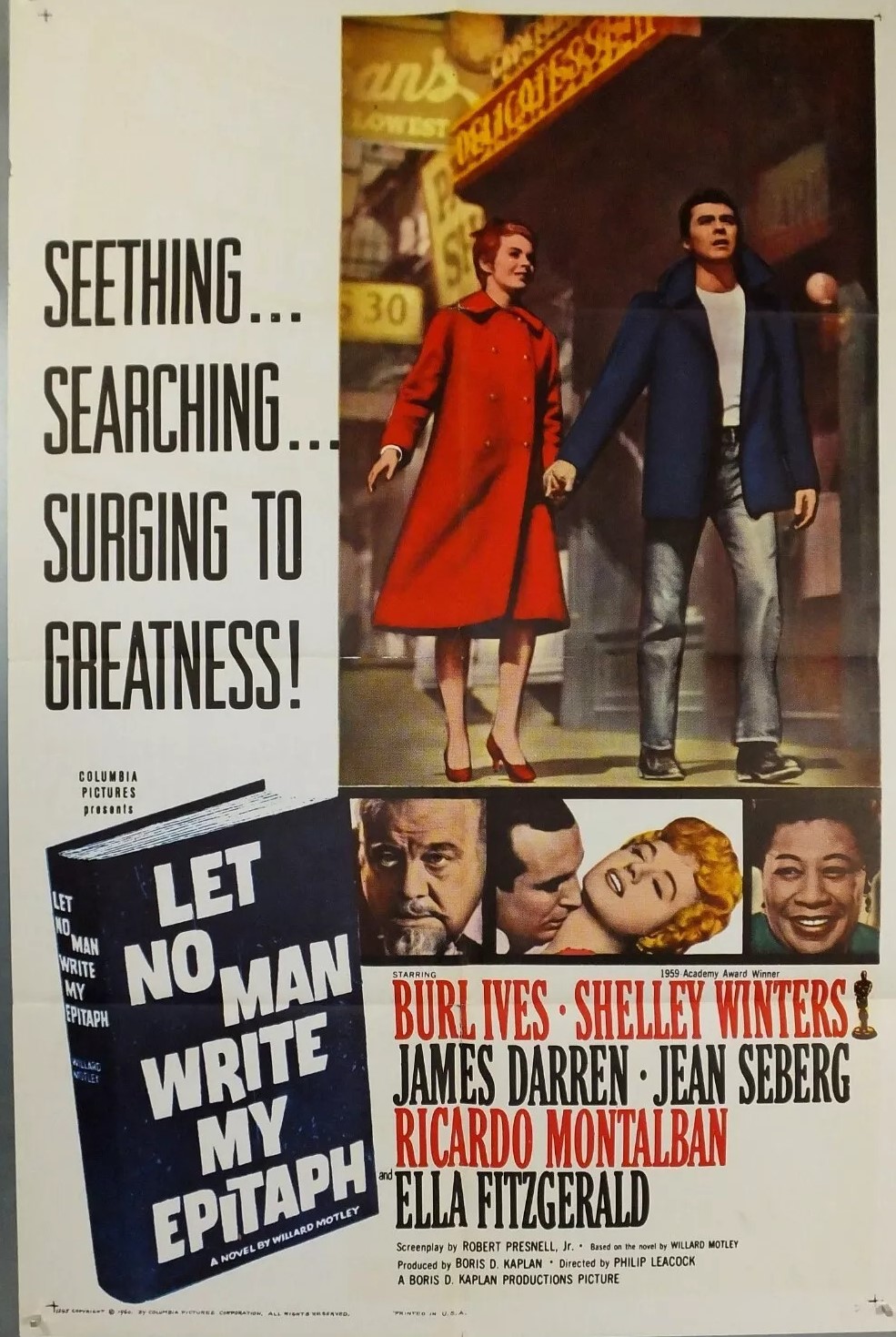

Both Telly Savalas (Sol Madrid, 1968) and Shelley Winters (A House Is Not a Home, 1964) rein in their normal more exuberant personas. Savalas, in particular, cleaves closer to his straightforward work in The Slender Thread than the over-the-top performance of The Dirty Dozen (1967). Winters, usually feisty, is here more winsome and vulnerable, apt to be taken in by sweet-talking men.

But Ossie Davis (The Hill, 1965) is the standout, his repartee spot-on. It is a hugely rounded performance, one minute wheedling, the next sly, boldness and cowardice blood brothers, and while his brainpower gives him the advantage over all the others he is only too aware that such superiority counts for nothing while he remains a slave.

It’s dialog rich and it’s a shame it wasn’t a big hit for that would have surely triggered a sequel – especially in the wake of the following year’s buddy-movie Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid – because the banter between Lee and Bass is priceless. For the dialog thank the original screenplay by future convicted gun-runner William W. Norton (Brannigan, 1975), father of director Bill Norton (Cisco Pike, 1971).

Go see.