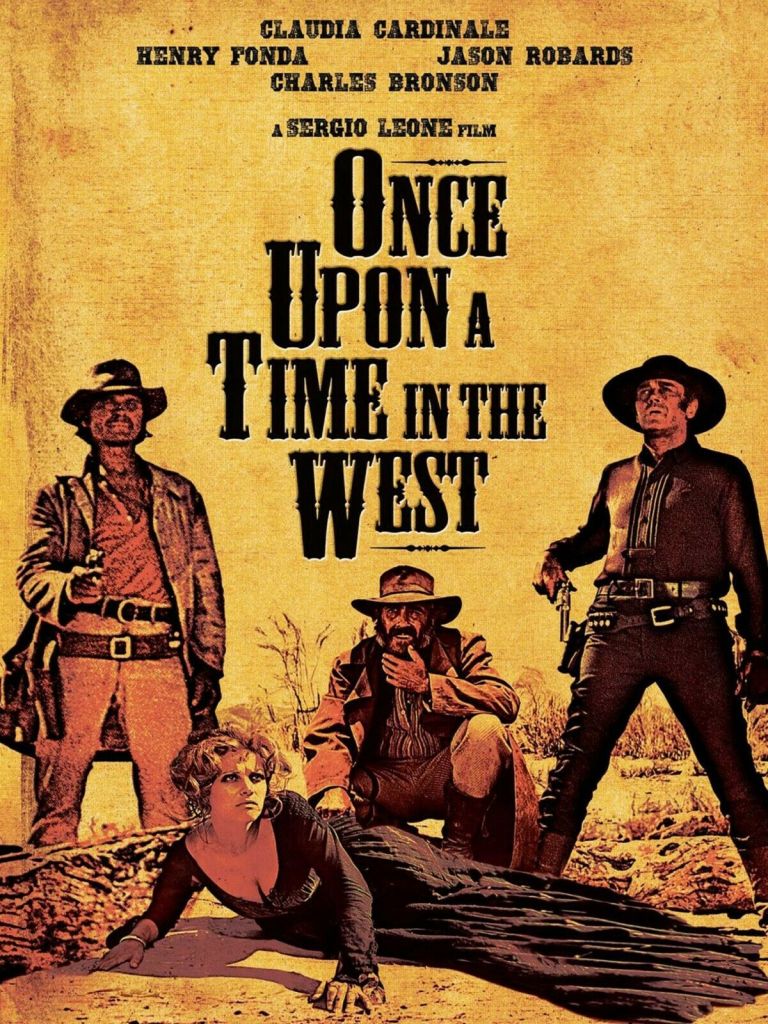

A masterpiece to savor. The greatest western ever made. Sergio Leone’s movie out-Fords John Ford in thematic energy, imagery and believable characters and although it takes in the iconic Monument Valley it dispenses with marauding Native Americans and the wrecking of saloons. That the backdrop is the New West of civilisation and enterprise is somewhat surprising for a movie that appears to concentrate on the violence implicit in the Old West. But that is only the surface. Dreams, fresh starts are the driving force. It made a star out of Charles Bronson (Farewell, Friend, 1968), turned the Henry Fonda (Advise and Consent, 1961) persona on its head and provided Claudia Cardinale (Blindfold, 1965) with the role of a lifetime. And there was another star – composer Ennio Morricone (The Sicilian Clan, 1969)

New Orleans courtesan Jill (Claudia Cardinale) heads west to fulfil a dream of living in the country and bringing up a family. Gunslinger Frank (Henry Fonda), like Michael in The Godfather, has visions of going straight, turning legitimate through railroad ownership. Harmonica (Charles Bronson) has been dreaming of the freedom that will come through achieving revenge, the crippled crooked railroad baron Morton (Gabriele Ferzetti) dreams of seeing the ocean and even Cheyenne (Jason Robards) would prefer a spell out of captivity.

The beginnings of the railroad triggers a sea-change in the West, displacing the sometimes lawless pioneers, creating a mythic tale about the ending of a myth, a formidable fable about the twilight and resurgence of the American West. In essence, Leone exploits five stereotypes – the lone avenger (Harmonica), the outlaw Frank who wants to go straight, the idealistic outlaw in Cheyenne, Jill the whore and outwardly respectable businessman Morton whose only aim is monopoly. All these characters converge on new town Flagstone where their narratives intersect.

That Leone takes such stereotypes and fashions them into a movie of the highest order is down to style. This is slow in the way opera is slow. Enormous thought has gone into each sequence to extract the maximum in each sequence. In so doing creating the most stylish western ever made. The build-up to violence is gradual, the violence itself over in the blink of an eye.

Unusually for a western – except oddities like Five Card Stud (1968) – the driving force is mystery. Generally, the western is the most direct of genres, characters establishing from the outset who they are and what they want by action and dialogue. But Jill, Harmonica and Cheyenne are, on initial appearances, mysterious. Leone takes the conventions of the western and turns them upside down, not just in the reversals and plot twists but in the slow unfolding tale where motivation and action constantly change, alliances formed among the most unlikely allies, Harmonica and Cheyenne, Harmonica and Frank, and where a mooted alliance, in the romantic sense, between Jill and Harmonica fails to take root.

There’s no doubt another director would have made shorter work of the opening sequence in Cattle Corner, all creaky scratchy noise, in a decrepit railroad station that represents the Old West, but that would be like asking David Lean to cut back Omar Sharif emerging from the horizon in Lawrence of Arabia (1962) or Alfred Hitchcock to trim the hypnotic scenes of James Stewart following Kim Novak in Vertigo (1958). Instead, Leone sets out his stall. This movie is going to be made his way, a nod to the operatic an imperative. But the movie turns full circle. If we begin with the kind of lawless ambush prevalent in the older days, we end with a shootout at the Sweetwater ranch that is almost a sideshow to progress as the railroad sweeps ever onward.

No character performs more against audience expectation than Jill. Women in westerns rarely take center stage, unless they exhibit a masculine skill with the gun. There has rarely been a more fully-rounded character in the movies never mind this genre. When we are introduced to her, she is the innocent, first time out west, eyes full of wonder, heart full of romance. Then we realize she is a tad more mercenary and that her previous occupation belies her presentation. Then she succumbs to Frank. Then she wants to give up. Then she doesn’t. Not just to stay but to become the earth mother for all the men working on the railroad.

Another director would have given her a ton of dialogue to express her feelings. Instead, Leone does it with the eyes. The look of awe as she arrives in Flagstone, the despair as she approaches the corpses, the surrender to the voracious Frank, the understanding of the role she must now play. And when it comes to close-ups don’t forget our first glimpse of Frank, those baby blue eyes, and the shock registering on his face in the final shoot-out, one of the most incredible pieces of acting I have ever seen.

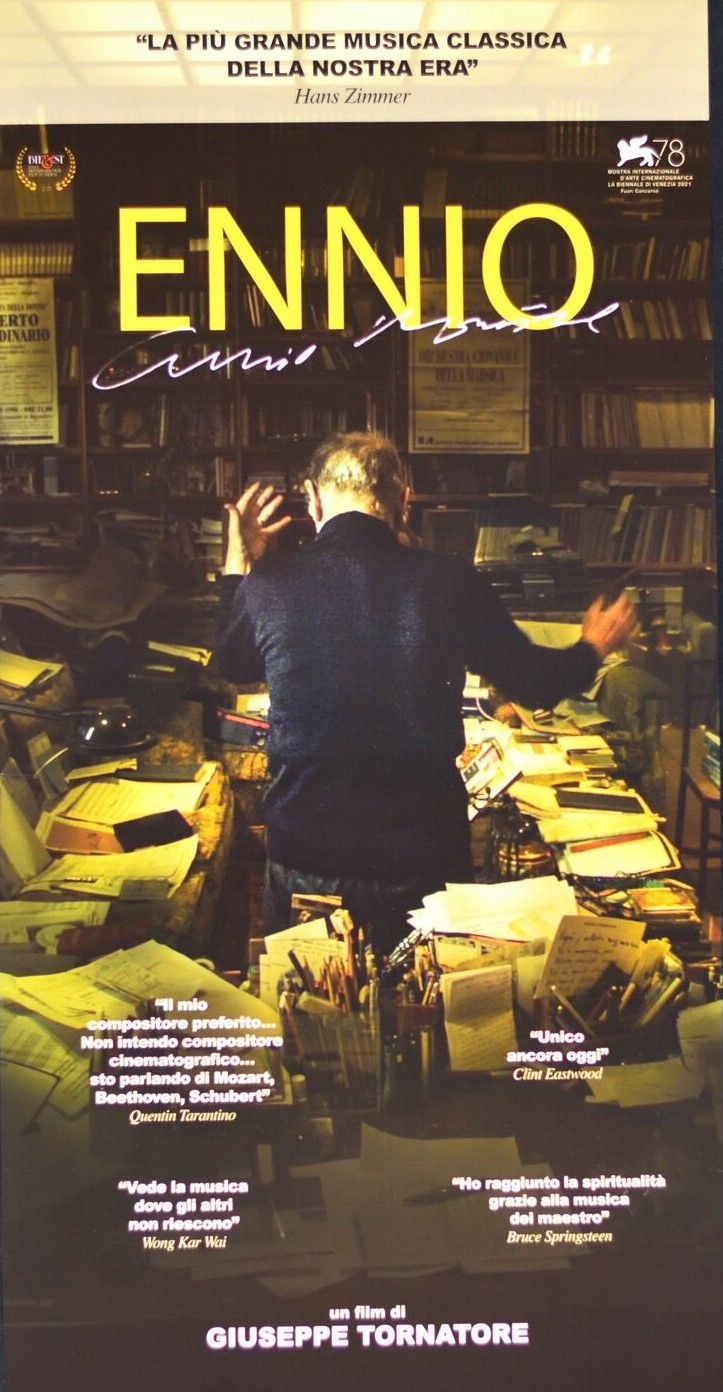

And you can’t ignore the contribution of the music. Ennio Morricone’s score for Once Upon a Time in the West has made a greater cultural impact than even the venerated John Williams’ themes for Star Wars (1977) and Jaws (1975) with rock gods like Bruce Springsteen and Metallica among those spreading the word to successive generations and I wonder in fact how people were drawn to this big-screen showing by the opportunity to hear the score in six-track Dolby sound. There’s an argument to be made that the original soundtrack sold more copies than the film sold tickets.

The other element with the music which was driven home to me is how loud it was here compared to, for example, Thunderball (1965), which as it happens I also saw on the big screen on the same day. Although I’ve listened to certain tracks from the Bond film on a CD where the context is only the listener and not the rest of the picture, I was surprised how muted the music was for Thunderball especially in the action sequences. Today’s soundtracks are often loud to the point of being obstreperous, but rarely add anything to character or image.

One final point, Once Upon a Time in the West was reissued not as some kind of retrospective for the director but in memory of the composer.