Had it been a hit in the U.S., it could have changed the way women were portrayed on screen.

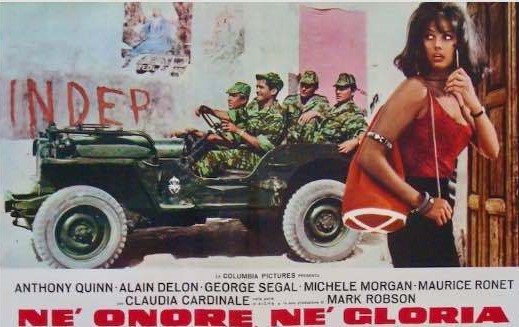

A box office smash could certainly have fired up a sequel (a key plank of the United Artists business model) and perhaps a reboot (Viva Marias! starring their daughters with or without the mamas). Could have led to the notion of Sophia Loren teaming up with Claudia Cardinale or Gina Lollobrigida and rescuing a captured male in a feminist twist on a western like The Professionals (1966). Imagine if it was Faye Dunaway and Jane Fonda carrying out the con caper in The Sting (1973).

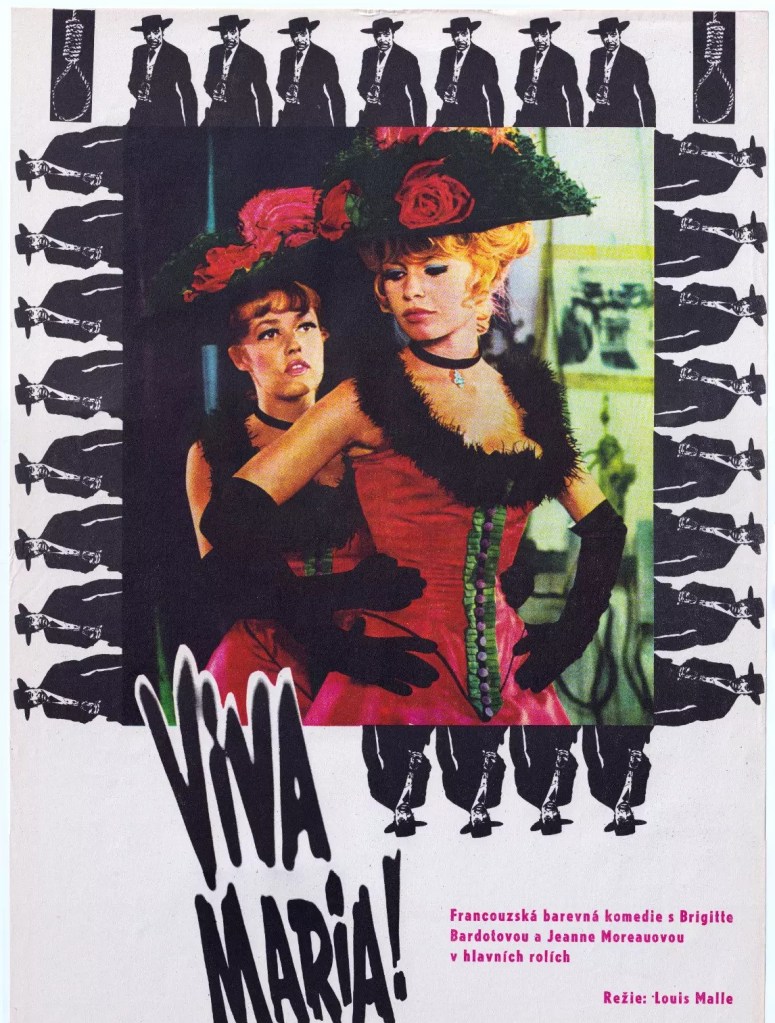

Until Viva Maria!, two top female stars only appeared together in a movie as rivals for a male’s attention, or if one was the victim of nasty behavior from the other, or one was heading for an untimely death leaving the other to hog the screen in a tide of emotion.

Although it still remained virtually impossible to have a pair of female stars appearing together unless for weepie or noir purpose, the impact of Viva Maria was considerable. For a start, it invented the buddy movie four years ahead of that subgenre’s official inception in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969).

The poster preceded Clint Eastwood in pointing weaponry hardware menacingly at the potential audience, Gatling rather than a .44 Magnum. Speaking of Gatling guns, might have given Sam Peckinpah ideas for employing that weapon in The Wild Bunch (1969).

Neither molls nor victims, these women fell at the first woman’s picture trope. They were not rivals in love. Maria II (Brigitte Bardot) is of a polyamorous disposition and expresses no interest in Flores (George Hamilton) the revolutionary lover of Maria I (Jeanne Moreau). Forget Julie Christie sowing wild oats in Darling (1965) or any other of the other liberated ladies of the decade, Maria II is streets head, acquiring – and discarding – men by the bunch.

Nor is Maria II particularly interested in becoming that other female fixture of the 60s – the rebel – given that she spent most of her childhood as an accessory to her insurgent father’s violent acts, rolling out detonating wire or pressing the plunger in locales as varied as Ireland and Gibralter before watching her father died in an act of sabotage that went wrong.

You would have thought that by this point in her career Brigitte Bardot (Shalako, 1969) could hardly get away with playing the innocent – setting aside her amoral intent – but audiences expecting titillation would have been surprised to see how quaintly she performs an accidental striptease which transforms their circus act, fortuitous really because Maria II has little sense of the rhythm required to be a stage performer.

Maria II resists becoming involved with Maria I’s messianic boyfriend but when he snuffs it she can hardly ignore his deathbed plea. The two Marias team up with the peasants to overthrow El Dictator (Jose Angel Espinosa ‘Ferrisquilla’) but not before they tangle with the Inquisition and the bad guys learn not to leave Gatling guns lying around. Would it be too much to argue that the female empowerment image of the decade is these two lasses spraying the enemy with bullets from the Gatling gun and, with more sense than Sam Peckinpah’s bunch, no intention of dying an heroic death.

It’s not a comedy in the normal sense, there’s no spoofing of revolution for a start, and it’s not so much filled with great one-liners as terrific sight gags. It’s more a drama with laffs. And, as you will be aware, revolution is good material for musicals – witness 1776 and Les Miserables, so don’t be surprised at the end to find our ladies treading the boards in Paris in a musical version of the revolution they have instigated.

Both Brigitte Bardot and Jeanne Moreau (Mademoiselle, 1966) throw acting caution to the winds, breaking out of the restraints of their screen personas, and almost as if freed from having to perform the dutiful female role of sacrifice, can turn their attention to embracing friendship and having a whale of a time doing so. George Hamilton (By Love Possessed, 1961) looks lost.

Most of what director Louis Malle (Atlantic City, 1980) attempts comes off though it might take you a little while to get to grips with the tone. Screenplay by Malle and Jean-Claude Carriere (Belle de Jour, 1967).

A blast.