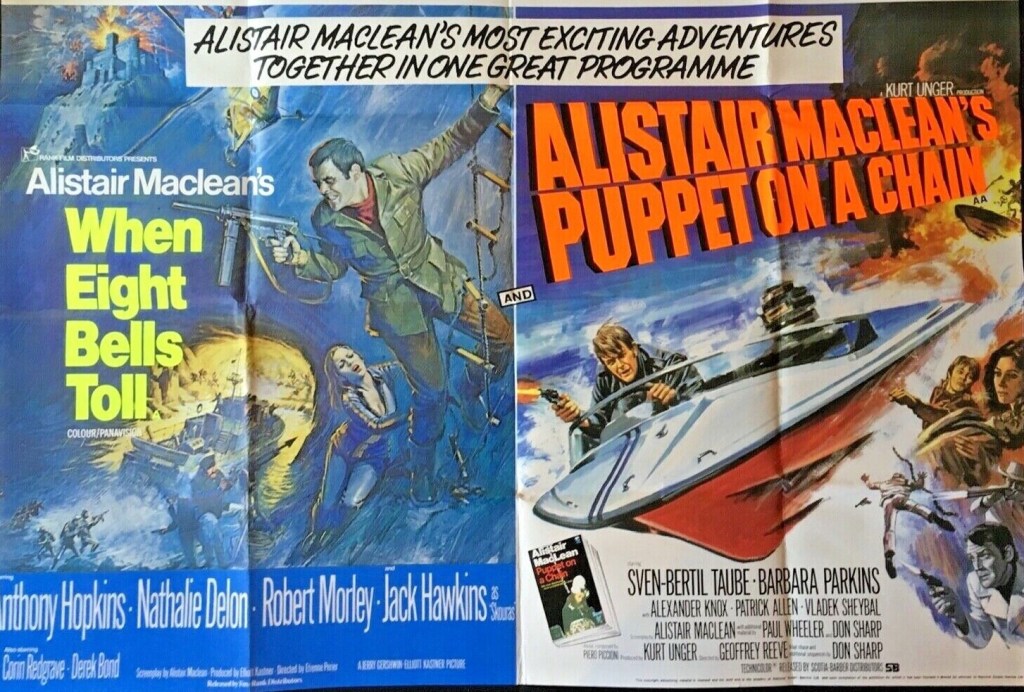

The spy genre was dying on its feet, even James Bond slipping into spoof territory, and it was left to Alistair MacLean to revive the genre with believable heroes and settings not just chosen for their scenic potential, fitting somewhere between the gritty policiers of Bullitt (1968) and The French Connection (1971) and with an emphasis on violence that Sam Peckinpah would be proud of.

Stylish bullet-ridden opening, crackerjack climax. In between depicting Amsterdam scenery and depravity side by side comes betrayal, duplicity, drugs, heinous deaths, plenty action, and as much as Bullitt (1968) reinvented the car chase this did the same for speedboats.

Tracking point of view follows an assassin into a house where he kills three people and removes something from the pendulums of clocks. U.S. narcotics agent Sherman (Sven Bertil-Taube) flies in to Amsterdam but before he can collect vital information from colleague Duclos he is murdered.

Top Dutch cops Col De Graaf (Alexander Knox) and Inspector Van Gelder (Patrick Allen) are helpless to stop the growing heroin traffic. Van Gelder, with addicted niece Trudi (Penny Casdagli), knows only too well the personal cost.The police force is riddled with leaks, the heroin gang out to stop Sherman from the get-go.

But Sherman has his own nasty medicine to deal out, and hands out beatings and death to those who get in his way. Helped by colleague Maggie (Barbara Parkins) and, inadvertently by Duclos’s girlfriend Astrid (Ania Lemay), the trail leads to the Morgenstern warehouse, which stocks all sizes of puppets, and a church run by shady pastor Meegeren (Vladek Sheybal) which has re-purposed Bibles.

Sherman has no sooner escaped one attempt on his life than he encounters another, so the action never lets up. Meanwhile, clues lead him to a boat in the harbor and he discovers how the heroin is being shipped. Maggie, on hand to offer romantic consolation, shares his tough assignment and questions his methods.

The trail isn’t that hard to follow but the obstacles are considerable. Meegeren and pals take hanging to the extreme, strangling victim on steel chains, dangling them high as a warning to others. So, mostly, leavened, depending on your point of view, by titillating views of the Dutch capital and a sexy dance troupe that would put Bob Fosse to shame, its fist- and gun-fights all the way.

Except for his dalliance with Maggie, a romance that has to be kept under wraps, Sherman fits the tough Alistair MacLean template with a ruthless streak wide enough to have won plaudits from Where Eagles Dare team He gets a good dousing in the sea and is an unwilling candidate for a brainwashing technique that combines tradition with a personalized version of the sonic boom.

But the highlight without doubt is the high-speed speedboat chase through Amsterdam, beginning in the wider Zuider Zee before racing through the narrow twisty Dutch canals.

For the Dutch Tourist Board it was a game of two halves, organ music aplenty, cobbles and canals, and people dressed in traditional garb promoting the city as a desirable destination but the unsightly addicts and the sex trade as likely to put overseas visitors off (although for many that may well be the icing on the cake).

It was rare at this point, in a polished Hollywood-style picture, to dig so deeply into the seamy side of a city, but his one pulls no punches, nitty-gritty winning out over gloss, and where Easy Rider (1969) and others of that ilk opted to canonize drugs this favored grim consequence.

It seems particularly difficult to get the casting right for an Alistair MacLean movie of the lone wolf variety – the all-star war pictures by contrast having no trouble attracting major players – and if you turned up your nose at Richard Widmark in The Secret Ways (1961), George Maharis in The Satan Bug (1965) and Barry Newman in Fear Is the Key (1972) you might quibble at Swede Sven Bertil-Taube (The Buttercup Chain, 1970). But he makes a fairly decent stab at the standard dour character.

Barbara Parkins (Valley of the Dolls, 1967), way out of her comfort zone, does well as the tough woman with a soft center. But, all told, you would say it benefits from largely casting unknowns as it prevents the audience arriving with preconceptions. In her only movie Penny Cadagli is the pick of the support, especially as her role in the movie is to play a role.

Although Geoffrey Reeve (Caravan to Vaccares, 1974) hogs the directing credit, the speedboat chase, other action scenes and the tightening up of the picture was the work of Don Sharp (Bang! Bang! You’re Dead, 1966). And Alistair MacLean didn’t, as he might have expected, receive sole screenwriting credit either, sharing it with Sharp and Paul Wheeler (Caravan to Vaccares, 1974).

Not only plenty of bang for your buck, but a riveting chase and one of the first sightings of heroin supply as the key driver of the narrative.