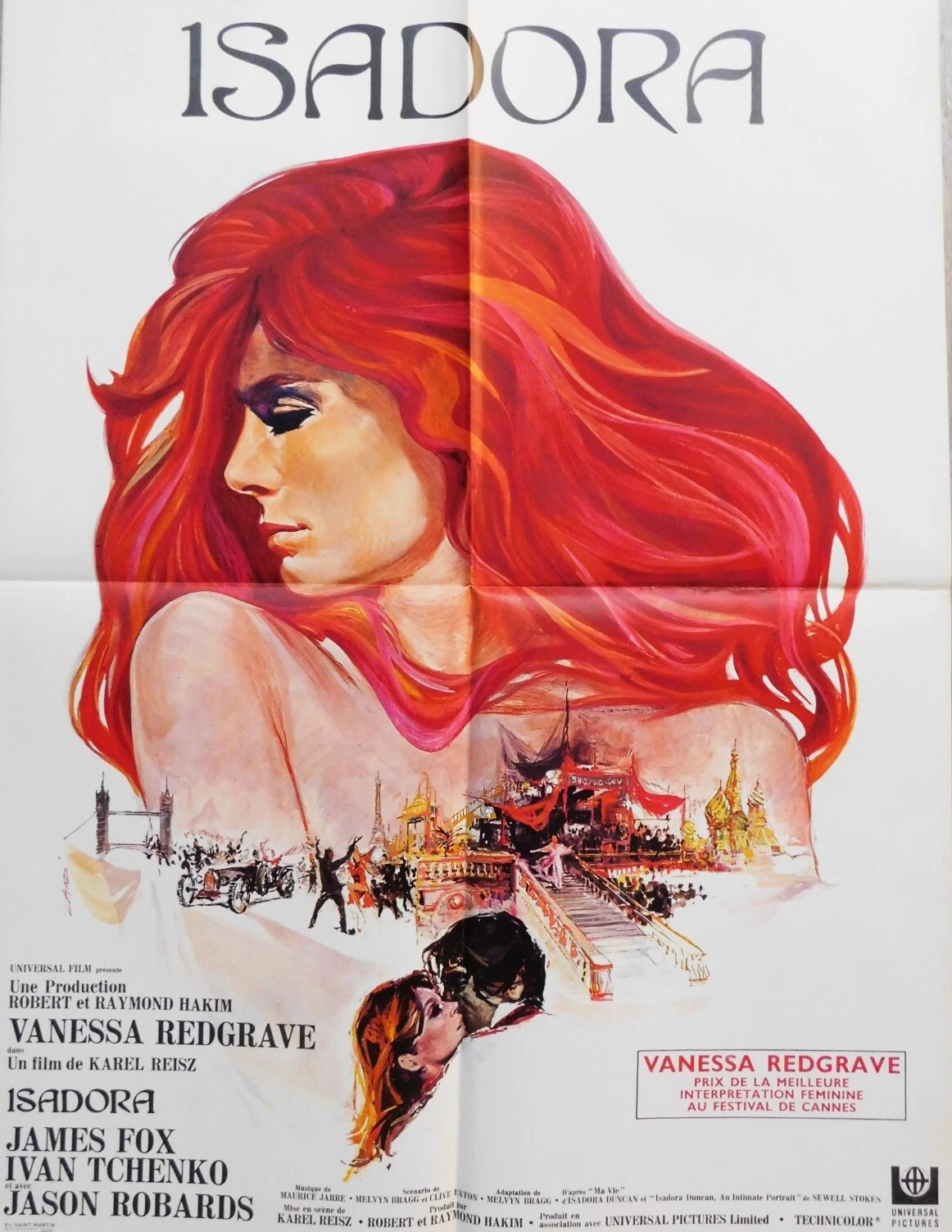

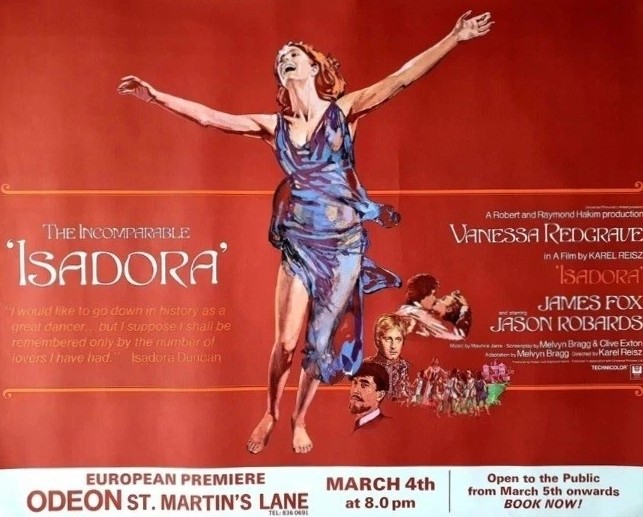

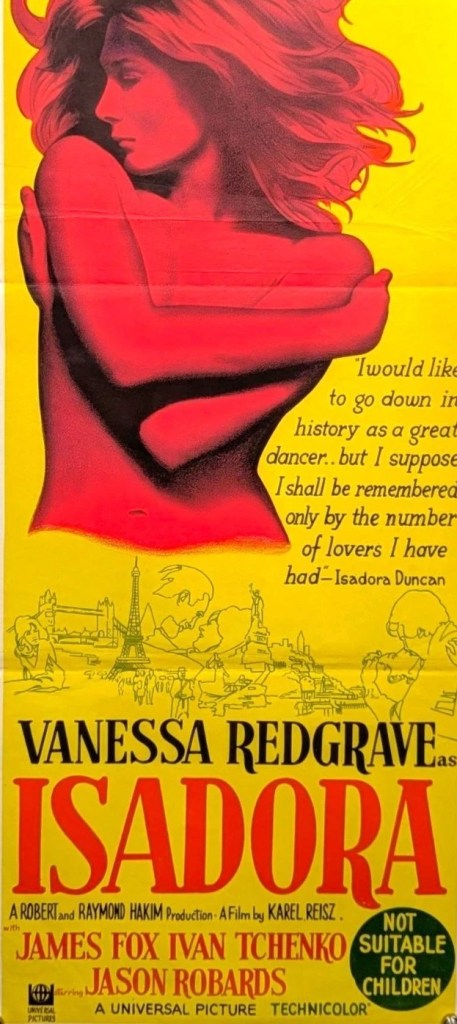

We’re two years away from the 100th anniversary of the death of feminist icon and pioneering dancer Isadora Duncan, but this movie has been in cold storage virtually since its release, so I’m wondering whether its sudden appearance on Amazon will trigger any interest in this long-forgotten, heavily edited, commercial flop of a movie.

Due to the clumsy structure it’s occasionally heavy going. We start off in Nice in the South of France where Isadora (Vanessa Redgrave) is dictating her memoirs to journalist (not lover) Roger (John Fraser) and the whole picture is rendered in flashback. And there’s something morbid about this structure, because essentially we’re waiting for her to die. Unfortunately, what she is most remembered for is getting her trademark long scarf tangled in the wheels of a moving Bugatti and snapping her neck. So we’re sitting around waiting for her to hop into a passing Bugatti with a Bugatti (Vladimir Leskovar).

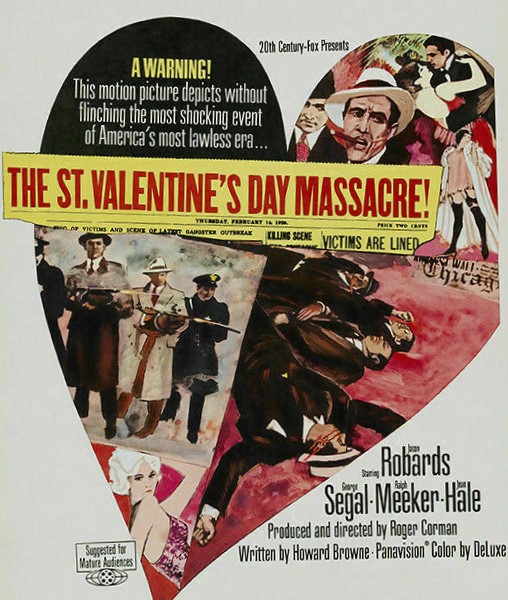

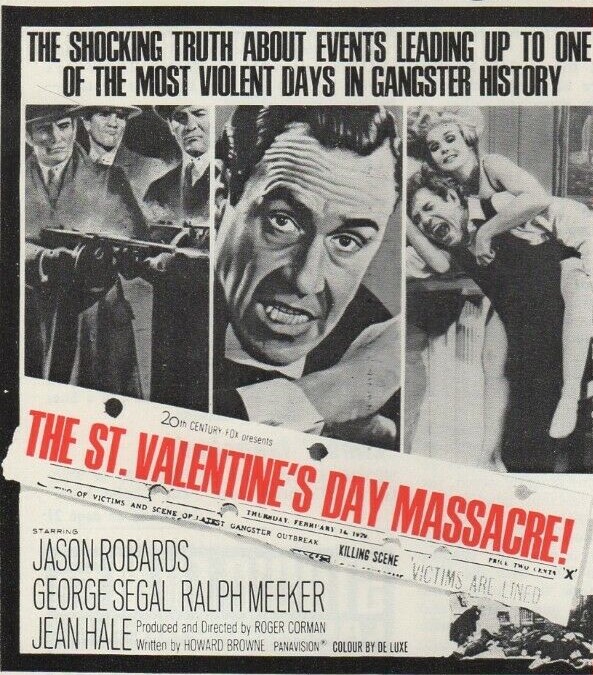

The rest of her life was somewhat fractured, consisting of her leaping from one lover/husband – Gordon Craig (James Fox), Paris Singer (Jason Robards), Romano Romanelli, Sergei Essenin (Ivan Tchenko) – to the next so characters appear and then disappear. Never mind her rebellious nature and determination to forge her own way and reinvent dance, her life was peppered with tragedy – all three of her children died, two drowning in the Seine (a fact repeated in a variety of ways to get the full emotional punch) – so there’s more than enough angst.

Her dancing is exuberant and uninhibited – she wore flowing dresses which looked as though any minute they would slip off her slender frame and there was scandal at one point when she bared her breasts during a performance. The first time she hits the stage is exceptionally ho-hum because it’s in a Paris nightclub and she’s a conventional, if very attractive, dancer of the ooh-la-la persuasion. But when she gets into her stride as a serious dancer, then visually it’s a treat, as she commands the stage – and screen- in a series of sexually provocative sinuous movements.

But, unfortunately, once is enough. You’d have to know a lot more about artistic dance than I do – and I guess the bulk of the original and contemporary cinematic audience – to know what changes she implemented and how, apart from her individual style (she danced solo not as part of an ensemble), her act developed and how it impacted on dance. She ran her own dance schools which probably liberated a ton of young women who were in the mood to be liberated.

But, as a biopic, even with 30 minutes knocked out, it’s way too long at the remaining 140 minutes, and the rest of the cast struggle to offer any competition to the lustrous Isadora.

Vanessa Redgrave, Oscar-nominated, is the best reason to watch and she is certainly compelling and, oddly enough, though there is plenty of incident and drama it somehow isn’t dramatically compelling.

She is generally naïve in her politics and her innocence in this department works to the advantage of the character. But mostly, we flit like a mobile time capsule through different periods, each well defined cinematically, and even though it’s clearly much harder to (in visual terms on film) convince as a genuine dancer than as, for example, a pianist, unless you were an expert on dance you wouldn’t know what to complain about.

You end up with a biopic about an interesting woman rather than a fascinating biopic. Vanessa Redgrave (Blow-Up, 1966) delivers another of her flawed characters and holds the screen effortlessly. The same cannot be said of the insipid males, James Fox (Thoroughly Modern Millie, 1967) and a miscast Jason Robards (Hour of the Gun, 1967).

Hard to know what the plans were of director Karel Reisz (Morgan!/Morgan, A Suitable Case for Treatment, 1966) because this isn’t his 168-minute version (the one that was released in the U.S. after disastrous opening weekend was trimmed to 128 minutes and in the UK to 140 minutes). Written by Melvyn Bragg (Play Dirty, 1969) and Clive Exton (10 Rillington Place, 1969) from a number of sources.

Sheds an interesting, but not enough, light on a legendary character.