There’s a classic MacGuffin in here somewhere, but I can’t make out if it’s the heist serving the satire on movies or the satire on movies serving the heist. Whatever, this is about the funniest picture you’ll watch on the movie business (much better than Paris When It Sizzles two years earlier). You can keep your royalty and your top politicians dropping in from every corner of the globe, but it’s hard to beat Hollywood landing on your doorstep to transform everyone into a sycophant. To facilitate filming, individual streets and solid blocks will be closed and even businessmen whose businesses are threatened will stick their nose out into the road in the hope of being captured by a stray camera. Everyone wants to be in the movies and how brazenly the movies exploit such naked need.

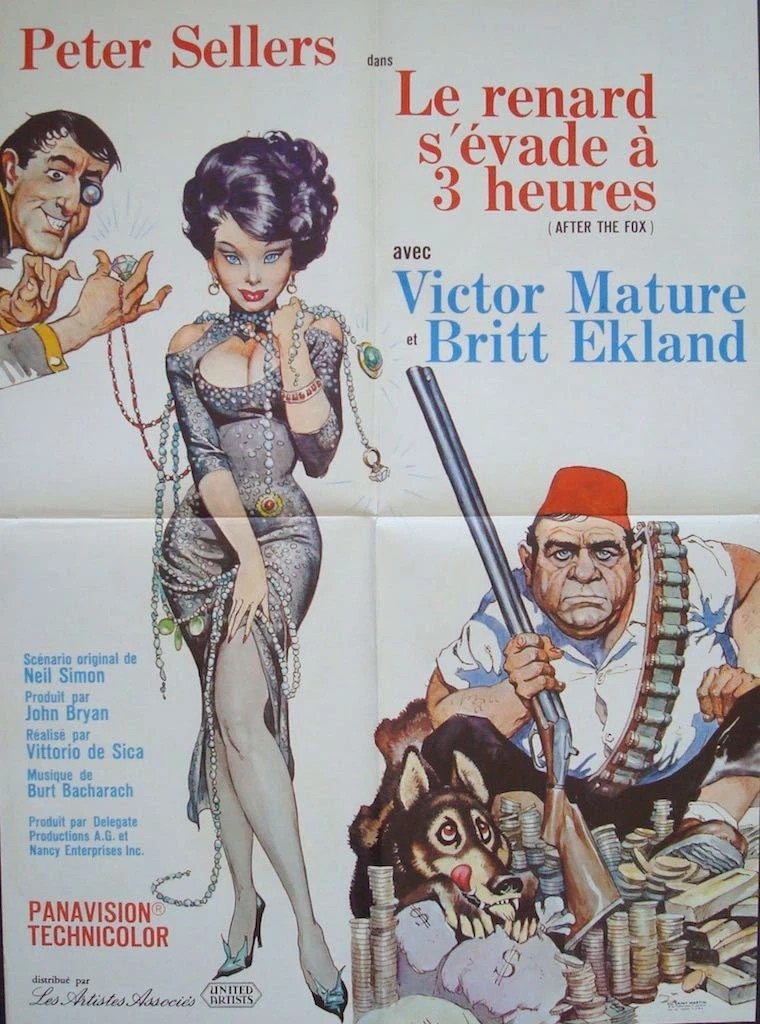

Before we get to the movie part of the story, we find imprisoned top criminal Aldo Vanucci aka “The Fox” (Peter Sellers) escaping from confinement so that he can assist robber Okra (Akim Tamiroff) transport 300 solid gold bars from a heist in Cairo to Italy. Though the heist is deceptively simple (and might even have influenced The Italian Job, 1969), for a time it looks as if this will canter along going nowhere fast while we get bogged down in a subplot concerning the burgeoning acting career of Vanucci’s sister Gina (Britt Ekland). There’s a whole bunch of standard Italian comedy tropes – the dominant Mama, the incompetent crooks and the brother too controlling of his sister.

But once Vanucci hits on a movie shoot as the ideal way to disguise the bringing ashore of the loot into the Italian island of Ischia, he strikes pure comedy gold. The townspeople who might otherwise easily see through a con man are putty in his hands. The local cop comes onside when persuaded he has the cheekbones of actor. Aging vain star Tony Powell (Victor Mature) wearing a trademark trench coat like a latter-day Bogart is an easy catch once you play upon his vanity and even hard-nosed agent Harry (Martin Balsam) is no match for the smooth-talking Vanucci.

Vanucci has mastered the lingo of the film director and can out-lingo everyone in sight. The very idea that he has a hotline to Sophia Loren goes undisputed and Powell is even persuaded that Gina, who has never acted in her life, is the next big thing.

Pick of the marvelous set-pieces is the scene in a restaurant where Vanucci is astonished to find a peach of a girl (Maria Grazia Buccella) speaking in a deep male voice because while she’s opening her mouth the words are being supplied by Okra seated behind her. Not all the best scenes involve Vanucci. Harry tartly batting away Tony’s vanities is priceless while the theft of film equipment while a film director (played by the movie’s director) calls for more dust in a sandstorm is great fun.

Also targeted is the self-indulgence of the arthouse filmmaker determined to add meaning to any picture. Vanucci’s versions of such tropes as lack of communication or a man searching for identity and running away from himself are a joy to behold and one scene of Tony and Gina sitting at opposite ends of a long table at the seashore just about sums the kind of pointless but picturesque sequence likely to be acclaimed in an arthouse “gem.” And you might jump forward to villagers hiding the wine in The Secret of Santa Vittorio (1969) for the sequence where townspeople load up gold into a van, singing jauntily all the time.

Most of all Sellers (A Shot in the Dark, 1964) hits the mark without a pratfall in sight – the only pratfall in the picture is accorded Harry. Unlike The Pink Panther, Sellers doesn’t have to improvise or be funny. He just follows the script and stays true to his character and the one he has just invented of slick director. There’s even a great sting in the tail.

Sellers shows what he can do with drama that skews towards comedy. Though criticized at the time for, effectively, some kind of cultural appropriation – she was a Swede playing an Italian, what a crime! – Britt Ekland (Stiletto, 1969) is perfectly acceptable. Victor Mature (Hannibal, 1960) has a ball sending up the business as do Akim Tamiroff (The Vulture, 1966) and Martin Balsam (The Anderson Tapes, 1971).

Vittorio De Sica (A Place for Lovers, 1969) does pretty well to merge standard Italian broad comedy with several dashes of satire. The big surprise is that Neil Simon (Barefoot in the Park, 1967) wrote the script, helped out by De Sica’s regular collaborator Cesare Zavattini (A Place for Lovers).

I saw this and A Shot in the Dark on successive nights on Amazon Prime. I hadn’t seen either before. They had been received at either ends of the box office spectrum, the Clouseau reprise a big hit, the Hollywood satire a big flop, so I expected my response might reflect that. But, in reality, it was the other way round. I appreciated this one more.

Go figure.