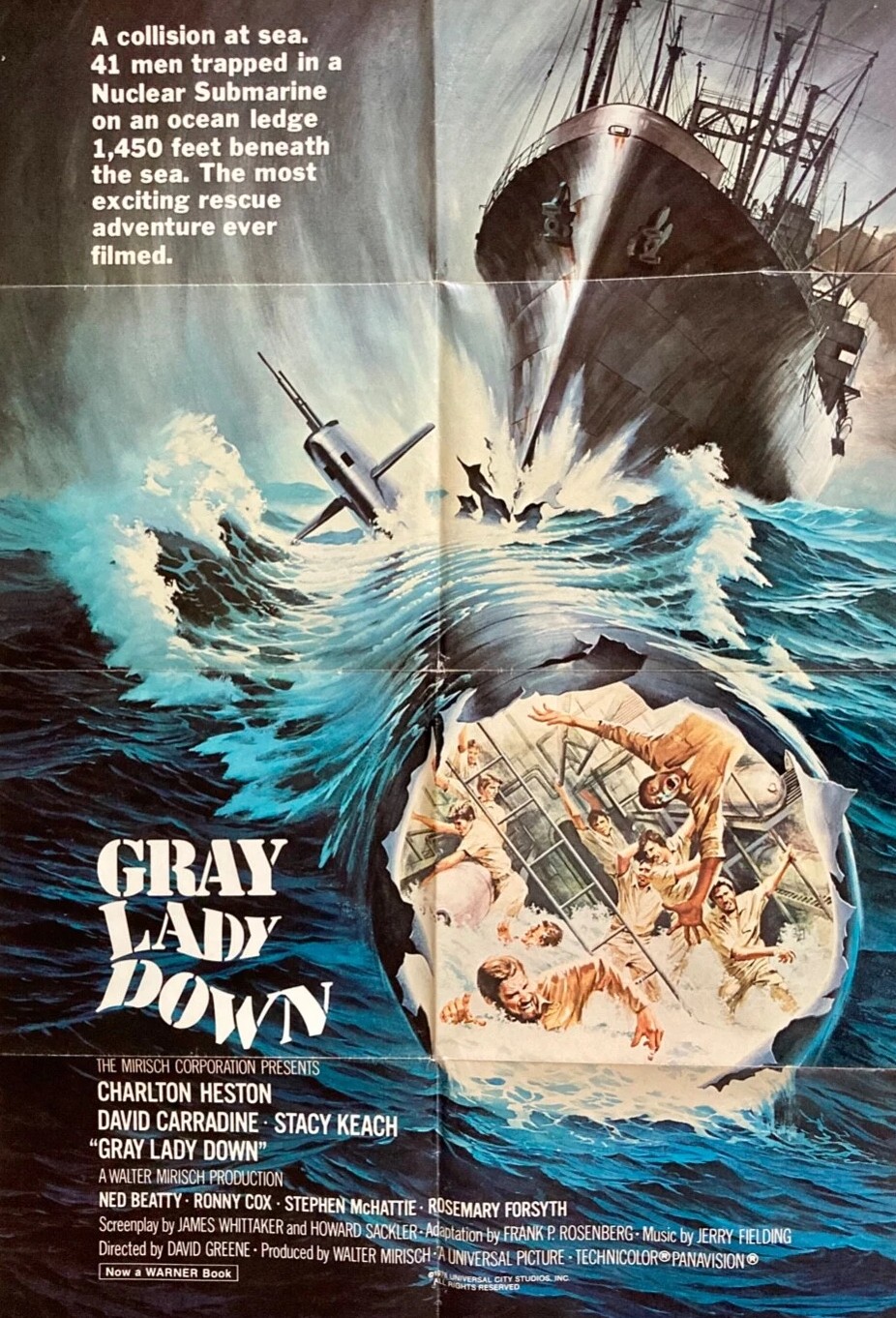

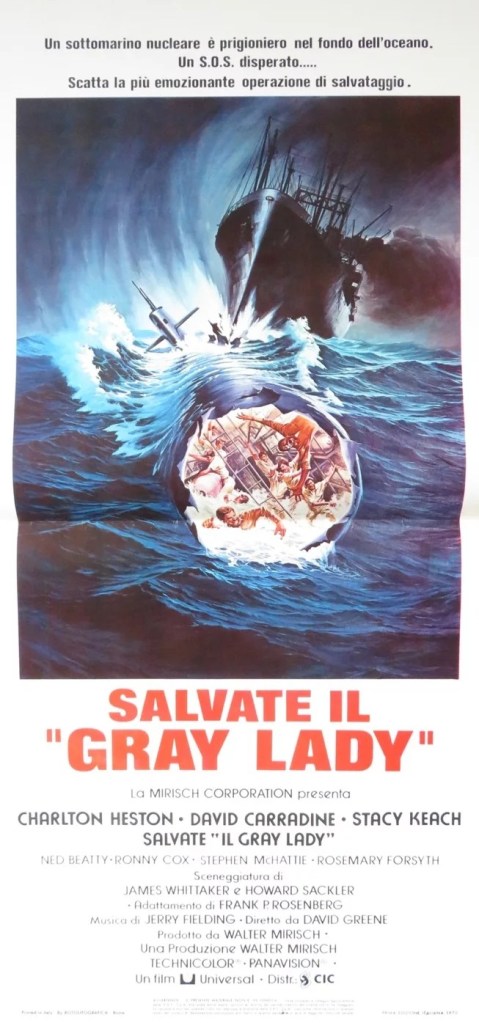

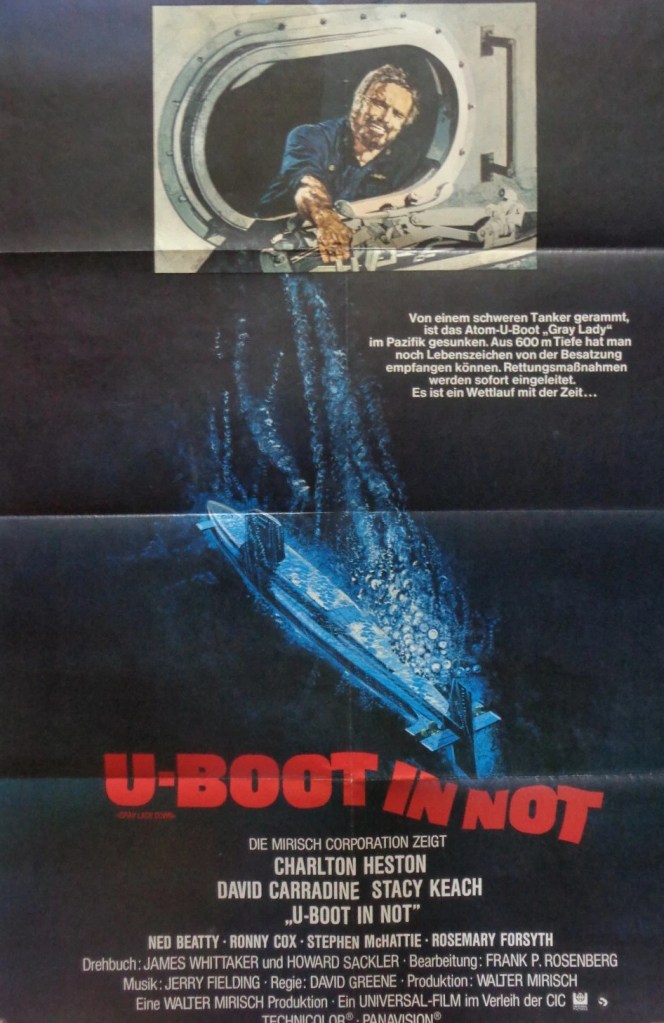

The best of the late 70s disaster pictures and possibly the best of the whole short-lived genre, mixing technology, hair-rising tension and restrained emotion on top of a belter of a concept, sailors trapped in a submarine on the seabed with oxygen running out. But what lifts this above the norm is that it doesn’t follow the normal disaster picture template. Men do not rise easily to this challenge. Courage drains away as fast as time. Tempers flare and more than one of these hardy men collapse under the pressure.

The best scene in the picture is a man dealing wordlessly with loss and being a male of a certain era unable to shed a tear. So it’s all on the face. Capt Blanchard (Charlton Heston) has to shut himself away to grieve. And there’s a somber tone throughout. Corpses, covered only in a blanket, are laid out alongside the injured in an improvised sick bay. More than one person cracks. Even in a major crisis, bureaucracy gets in the way.

Blachard isn’t exactly the strong-jawed hero. As the situation grows more serious, his equanimity fails and he gets very snappy with the crew. And he’s also dealing with a heavy dose of guilt. Luckily, his major failing isn’t exposed to the crew, but his second-in-command points the finger.

Although the sub has been sent to the bottom courtesy of a collision in thick fog with a merchant ship boasting faulty radar, the accident should never have occurred. The sub shouldn’t have been on the surface. The only reason for that was Blanchard’s pride. This is his final voyage and he wanted to sail into harbor with is vessel atop the waves.

Now the sub is laid up in a deep trench and subject to “gravity slides”, the technical term for rock falls, which not only shift its position every now and then, pushing it deeper into the trench, but seal up the top of the escape hatch.

So the U.S. Navy’s new-fangled DSRV (Deep Submergence Rescue Vehicle) can’t do its job and an even more new-fangled experimental submersible, operated by Captain Gates (David Carradine) and his sidekick Mickey (Ned Beatty) is called in. But its operation is sabotaged when officious Capt Bennett (Stacy Keach), tasked with the rescue mission, insists on one of his own men going down instead of the more experienced Mickey.

The underwater scenes are thrilling, and there’s plenty of technical know-how on view and a bunch of impression jargon spouted, as the sub slips further away and the submersible moves into more perilous depths. In the days before CGI, this is superb stuff. And since the sub is now upside down you certainly see more than normal of your typical submarine.

Unlike earlier disaster numbers like Airport (1970), The Poseidon Adventure (1972) and Towering Inferno (1974), no time is wasted setting up the various characters, usually embroiled in emotional entanglement, and for sure there’s no nuns or pregnant women to get in the way of a tight narrative. Comic relief, if that’s what you’re looking for, is provided by the chirpy Mickey.

But when you get right down to it, this holds all the narrative aces. You know rescue is going to get complicated. The unexpected always gets in the way.

But the men under pressure a thousand feet blow the surface are really under pressure and it’s not long before the cracks begin to show and widen.

Unfortunately, this came at the tail end of the disaster cycle when public interest was waning, and perhaps precisely because there was a lack of male-female interaction and no nuns it proved less appealing.

Charlton Heston (Will Penny, 1968) is very impressive, especially when he strains to hold it together and the scene I mentioned is one of his most best pieces of acting. Ned Beatty (Deliverance, 1971) also has a top-notch stiff-upper-lip scene.

Topping the supporting cast are David Carradine (Heaven with a Gun, 1969) and Stacey Keach (Fat City, 1972). You can spot Christopher Reeve (Superman, 1978) in an early role. Rosemary Forsyth (The War Lord, 1965) has a small part, but onshore.

Ably directed by David Greene (Sebastian, 1968) from a screenplay by James Whittaker (Megaforce, 1982) and Howard Sackler (The Great White Hope, 1970) based on the book by David Lavallee

If you’re in the mood for a thrilling ride, hang on to your hat.