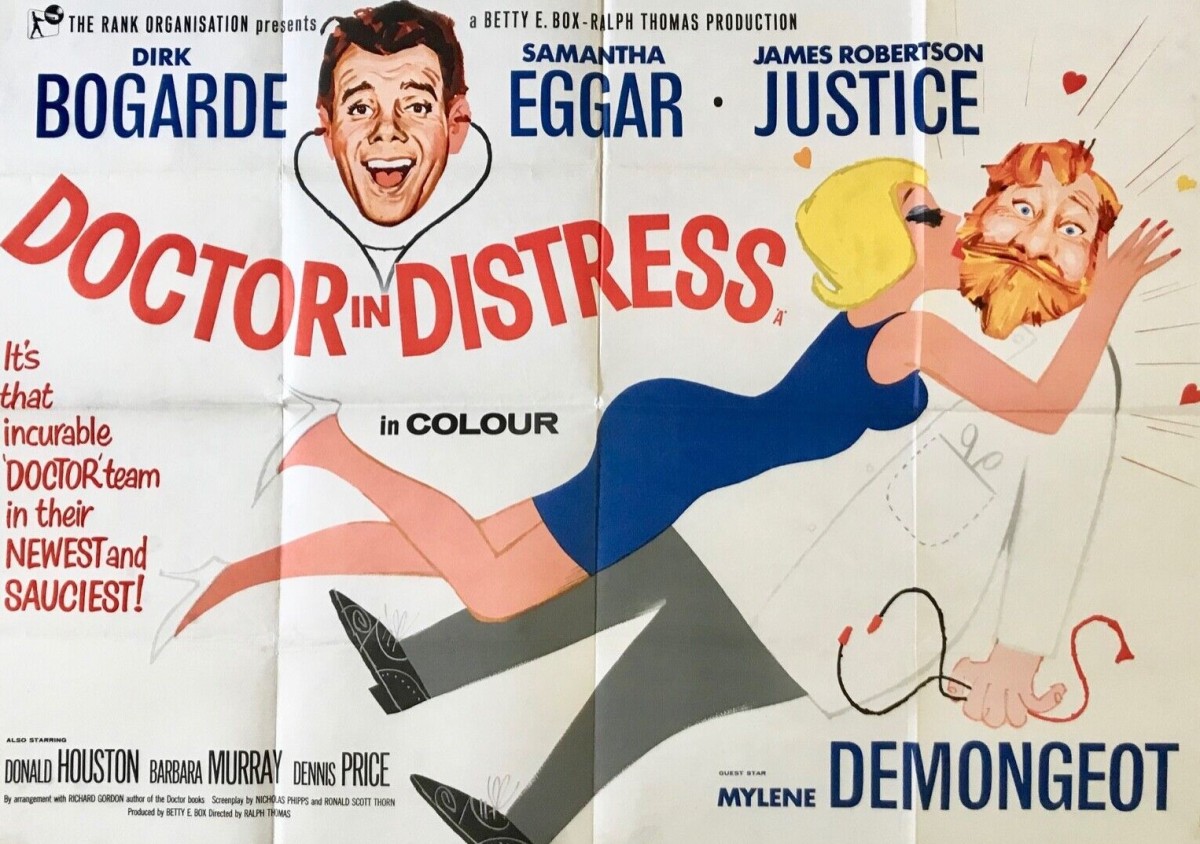

Bait-and-switch as the romantic complications of the grumpy Dr Spratt (James Robertson Justice) take precedence over the by-now pretty competent Dr Sparrow (Dirk Bogarde). Just about getting by on Bogarde’s charm in his fourth and final outing in a role that had made him a British box office star and possibly more notable as his final film as an out-and-out matinee idol before he shifted into the arthouse arena.

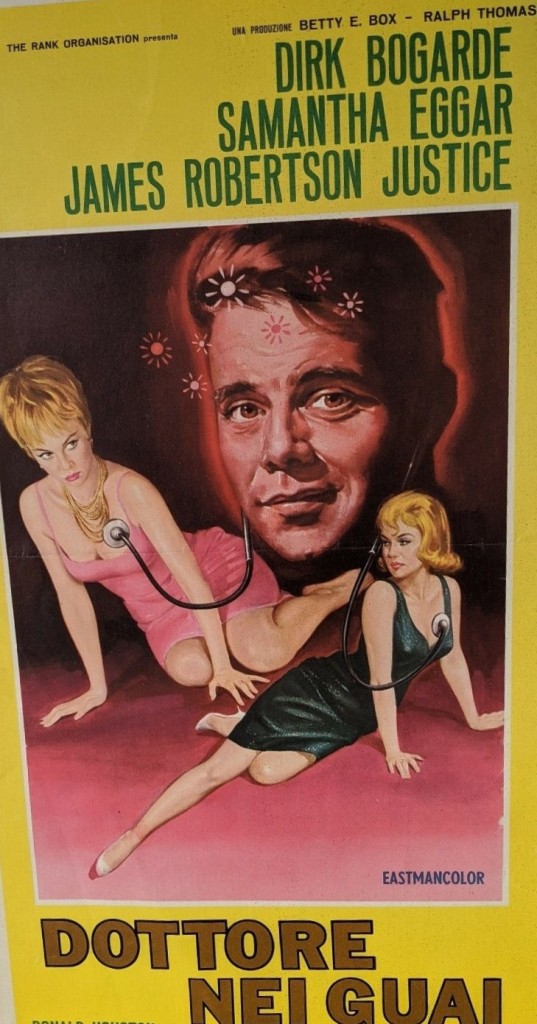

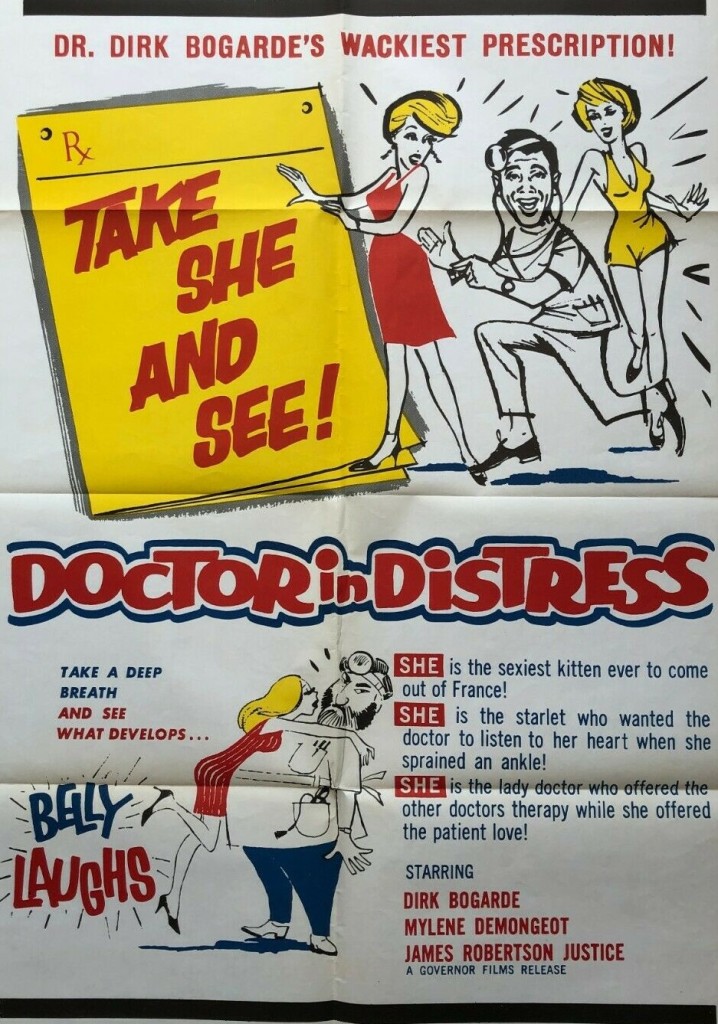

Dr Sparrow has come a hell of a long way since being a shy junior doctor, mercilessly bullied by Spratt and a love life that was filled with tangle. Here, he not only stands up to Spratt, but is something of a lothario, happily ditching new love Delia (Samantha Eggar), a model, albeit temporarily, in favor of French masseuse Sonia (Mylene Demongeot).

There is very little of the traditional rom-com-love-on-the-rocks in Bogarde’s relationship with Delia, who arrives as a patient with a sprained ankle at the hospital and is whisked home by Sparrow for a spot of practised seduction. Spratt, on the other hand, has fallen for physiotherapist Iris (Barbara Murray) and in trying to win her hand undergoes weight loss treatment at a health clinic, endures the indignity of wearing a corset, hires a private detective to get the lowdown on her, and finally, donning a disguise of dark glasses and hiding his bulky frame behind an umbrella, proceeds to attempt to discover who is his rival for her affections.

Sparrow is left to occasionally swat out of the way the interfering Spratt and alternatively offer him advice or a shoulder to cry on while trying to prevent Delia pursuing a movie career. So it’s just a series of situations, none of which are particularly funny, apart from the idea of Spratt getting his come-uppance.

It’s worth noting that for a British sex comedy, the females are in charge. Iris knocks back her various suitors, Delia refuses to let romance interfere with her career, jetting off to Rome over Sparrow’s objections, and the diminutive and muscular Sonia is more than a match for any man and just as predatory.

What’s most surprising is that a genial comedy like this can get away with so much permissiveness. This was opposite of the in-your-face snigger-snigger Carry On series so for Sparrow to be successfully spreading his wild oats seemed somewhat out of character. But you can see most of the jokes a mile off though probably in a packed cinema these would provoke more laughter than watching it at home on the small screen.

It’s probably worth it to see Leo McKern (Hot Enough for June, 1964) as a movie producer who envisages Sparrow as his new star and Frank Finlay as a corset salesman, a completely different role to his part in Robbery (1967). Fenella Fielding (Lock Up Your Daughters, 1969) has a cameo as a neurotic passenger on a train and Dennis Price (Tunes of Glory, 1960) as a sadistic health clinic manager while Donald Houston (A Study in Terror, 1965) has a larger part as another of Iris’s suitors.

Dirk Bogarde (Justine, 1969) can essay this kind of character in his sleep but there is no doubting his screen charisma or charm. But I doubt if James Robertson Justice (Mayerling, 1968) varied his character much from picture to picture, perhaps louder and more bumptious here but unlikely to attract audience sympathy. Samantha Eggar (The Collector, 1965) doesn’t get enough to do and has her thunder stolen by the late arrival of Mylene Demongeot (Fantomas, 1964).

Director Ralph Thomas had made more than a half-a-dozen films with Bogarde including more dramatic ventures like Campbell’s Kingdom (1957) and The Wind Cannot Read (1958) and makes the most of this undemanding feature. You would have thought this was the end of the line for the series but with Leslie Phillips (Maroc 7, 1967) as Bogarde’s replacement it soldiered on for another couple of episodes.

Proof that a true star can always help a film rise above its material.