Contemporary audiences will gib at a narrative that relies on legalised rape. Audiences at the time had the same response but since then it has picked up considerable critical acclaim on account of its down-and-dirty portrayal of a medieval era far removed from the knight in shining armour. But it still pivots on the distasteful notion of “droit de seigneur”, the right of any noble to take the virginity of any female underling on their wedding night – it was motivation for William Wallace’s rebellion in Braveheart (1995).

The idea that this was pervasive or even occurred at all has been proven to be historically inaccurate. Logic tells you that any ruler wanting to keep his subjects in check would scarcely resort to wholesale rape that could spark disloyalty among his subjects. Or that any no one would be unaware of the dangers of inbreeding should the nobleman’s seed result in pregnancy.

What of course the movie does get right is that women were treated as chattels – “she’s mine” / “you’re mine” a recurrent refrain – or were makeweights in deals uniting the vested interests of kings or dukes.

As reward for years of service to the Duke of Ghent, Chrysagon (Charlton Heston) is handed a fiefdom in Normandy, prone to attack by Frisian raiders from the neighbouring Netherlands. In interrupting such an assault, Chrysagon captures the enemy chief’s son without being aware of it, prompting a later battle.

While the area boasts vestiges of normality, a priest and a strong tower, the inhabitants are inclined to the pagan rather than Christianity with rites (reminiscent of Game of Thrones) involving stone and trees while anyone using herbs for medicinal purposes is likely to be accused of witchcraft. Chrysagon takes a fancy to Bronwen (Rosemary Forsyth) already bethrothed to Marc (James Farentino). Egged on by his brother Draco (Guy Stockwell), Chrysagon decides to take up the option of droit de seigneur, but refuses to return the bride after the allotted time period (before dawn), incurring the wrath of the villagers who recruit the Frisians to their cause.

So it’s siege time although it seems unlikely that the attackers would be capable of producing such dangerous siege weapons in such a short time or that they wouldn’t simply resort to starving out the beseiged. Chrysagon’s troops engage the attackers in time-honoured fashion from the top of the tower by arrow, boulders and boiling oil. Chysagon slides down a rope like Errol Flynn to prevent the raised drawbridge being lowered and uses a boat anchor to dislodge the siege tower. Battering rams and catapults soon enter the equation.

The only question-mark (unspoken) against Chrysagon’s employment of the “droit” privilege comes when the Duke demotes him and appoints Draco in his stead, prompting various endgame twists.

The battle is interesting enough, threat repeatedly countered, but there’s only so many times a director can cut to a soldier tumbling to his death. The ending is an anomaly, Chrysagon showing more respect to the son of his enemy than the wife of his villagers, and it seems odd that Draco is suddenly revealed as a bad guy, despite not being the one who triggered the conflict.

Chrysagon might have easily have fallen into the Martin Scorsese category of characters with “no redeeming features” – who are exempt apparently from the need for decency because of war – and it’s hard to summon up the necessary audience sympathy to make this picture work, especially given its starting point. Had Chrysagon merely fallen in love with Bronwen who reciprocated his feelings and that caused enmity among the villagers it would have been one thing but to start out from an historically inaccurate base is another.

One of the problems is that Bronwen doesn’t evolve. Her transition is from interesting to passive. She has actually gone through a marriage ritual (of the Druid kind, but still binding as far as the villagers are concerned) and is therefore embarking on an adulterous relationship once the cock crows. It seems ludicrous, without allowing the woman dialog to express her feelings and acknowledge the peril of her actions, that she would believably take this route.

So, if you like, accepting the droit de seigneur, in some ways it becomes a bolder picture, a major Hollywood star risking his reputation by playing a rapist, and in the way of all rapists justifying his action. And, like the characters in the recently-reviewed Play Dirty (1969) or Judith (1966), it becomes a question of individuals as pawns, the powerful taking advantage of position to abuse the weak. And it wouldn’t be the first time the innocent have suffered through a superior taking an indefensible approach.

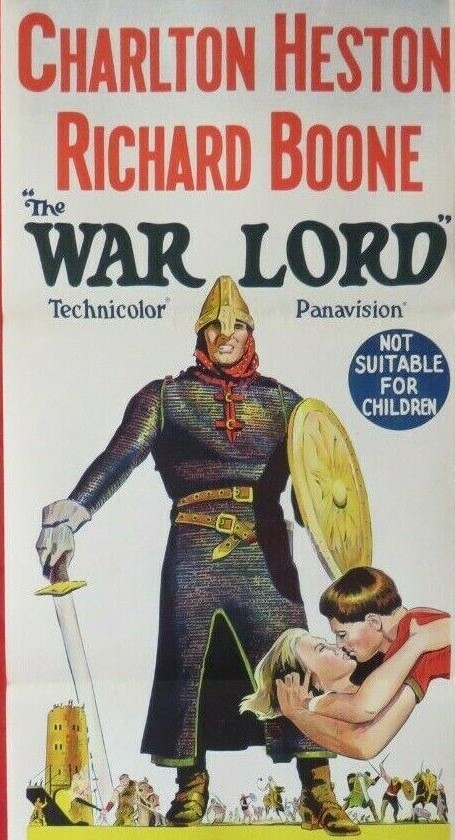

Franklin Schaffner (Planet of the Apes, 1968) directed. Charlton Heston (Diamond Head) performs as if he’s the French equivalent of a Brit constantly biting on that stiff upper lip. Richard Boone (Rio Conchos, 1964) is wasted. Guy Stockwell (Tobruk, 1967) essays another weasel. It’s a picture of two halves for Rosemary Forsyth (Where It’s At, 1969) – while being wooed she’s good but then she’s pretty much dumped as far as the narrative goes.

Screenwriter John Collier, who later wrote the even creepier Some Call It Loving (1973) – an early Zalman King production – and Millard Kaufman (Raintree County, 1957) adapted the screenplay from an unusual source, a Broadway play by Leslie Stevens (Incubus, 1966) called The Lovers. The play had a different perspective, the bride ultimately committing suicide, while the War Lord and husband killed each other in a duel. Needless to say, there are no Frisians, so no siege, and no brother.

Before the arrival of Ridley Scott, this would been viewed as the best depiction of genuine medieval siege, so that part certainly still holds up. But the rest of it will only stand the test of time if you are willing to view it as an expression of the corruption of power.