As far as Hollywood was concerned brainwashing was ascribed to foreigners intent on disrupting democracy as with The Manchurian Candidate (1962). Such inherent hypocrisy will come as no surprise since scientists at McGill University in Canada had been carrying out C.I.A.-funded sensory deprivation experiments in the 1950s. Where the John Frankenheimer paranoia thriller went straight down the political route, The Mind Benders, based on the McGill tests, is more interested in the personal cost, although ruthless politicians and unscrupulous scientists still abound.

The suicide of renowned scientist Professor Sharpey (Harold Goldblatt), possibly selling secrets to the Russians, sends MI5 agent Major Hall (John Clements) to Oxford to investigate sensory perception tests. The guinea pigs have all been volunteers, keen to expand knowledge of human mental endurance. The latest volunteer, Dr Longman (Dirk Bogarde), is on leave recovering from his participation. To avoid branding Sharpey a traitor it is proposed that he was actually brainwashed by long immersion in a water tank and subsequent sensory deprivation.

In order to prove the point, Longman, a driving force behind the research having shifted the focus from sub-zero temperatures to water, is the unknowing guinea pig, a jealous colleague Dr Danny Tate (Michael Bryant) who fancies his wife Oonagh (Mary Ure) suggesting that the experiment would be deemed a success if Longman was turned against his wife. It transpires that sensory deprivation has already had an effect on Longman, his wife complaining his lovemaking has grown rough.

The callousness with which this stage of research is undertaken, the disregard not so much for human life but emotion and love, in a country that prides itself on honor and fair play, sets up a different register to the Frankenheimer film where at issue is the assassination of the most important person in the United States. Longman, fed lies about his wife’s infidelity, becomes a different character, distrustful, aggressive, embarking on an affair of his own, putting in jeopardy the happiness he has constructed.

Ahead of its time in analyzing the importance of the hidden persuaders (as television advertising would later be termed) and lacking a thriller element to drive the narrative, nor devised as a self-indulgent experiment like the later Altered States (1980), nonetheless this achieves tremendous power through the deliberate dislocation of individual life, personalizing in a way that others in the paranoia thriller genre do not the dangers of tampering with the unknown.

And perhaps because it is so British, with the Longman family living in a big rambling house, the children involved in myriad games, the scientist a loving husband, that the outcome is so horrible. Brainwashing was seen as a form of torture, with subjects susceptible to ideas they may have once opposed, almost forming a new identity.

The structure here sucks in the audience. It’s ostensibly initially about spies, outing a traitor, a notion that every British citizen would go along with, the film especially relevant in the wake of the Kim Philby affair the year of the film’s release, when the idea of “spies among us” took root. Then we move on to a scientific account of the deprivation experiment, the first one taking place in the Arctic Circle, footage of a volunteer emerging in a fugue state. When Longman does another experiment, himself the guinea pig, to show what is involved, the various changes the body and mind undergo, it still seems far removed, captivating and intriguing though it may be, from any human horror.

But when Longman becomes the unknowing victim, the audience becomes privy to the worst aspects of the brainwashing. The personal price paid would put every member of the audience off endorsing its use.

This is a very measured film, cunning in its construction, that puts the viewer at the heart of the story. Without spelling out the psychological terror, the implications are nonetheless clear, a nightmare from which there is no escape, no guarantee the process could be reversed, men turned into different personalities at the behest of government for who knows what end.

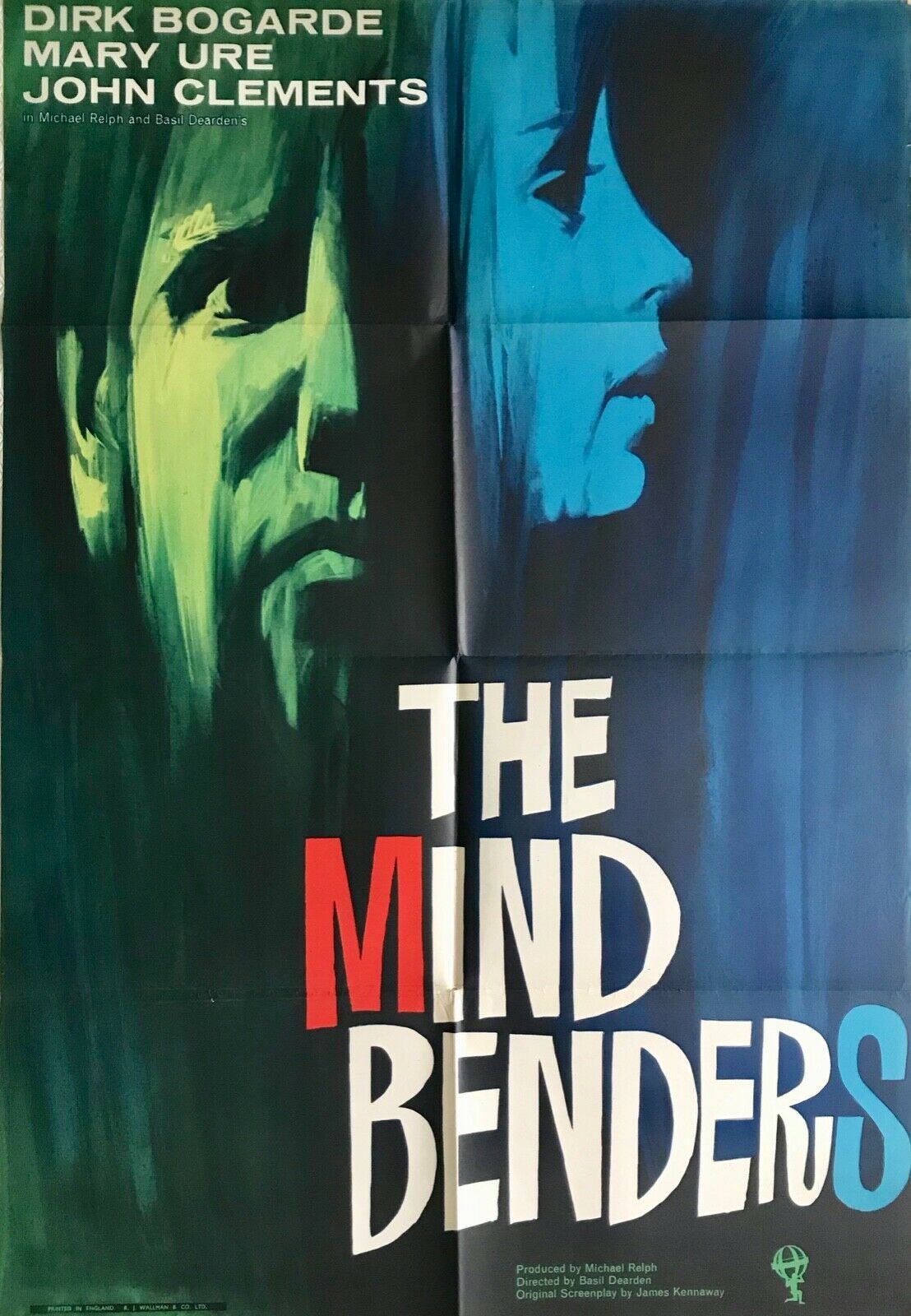

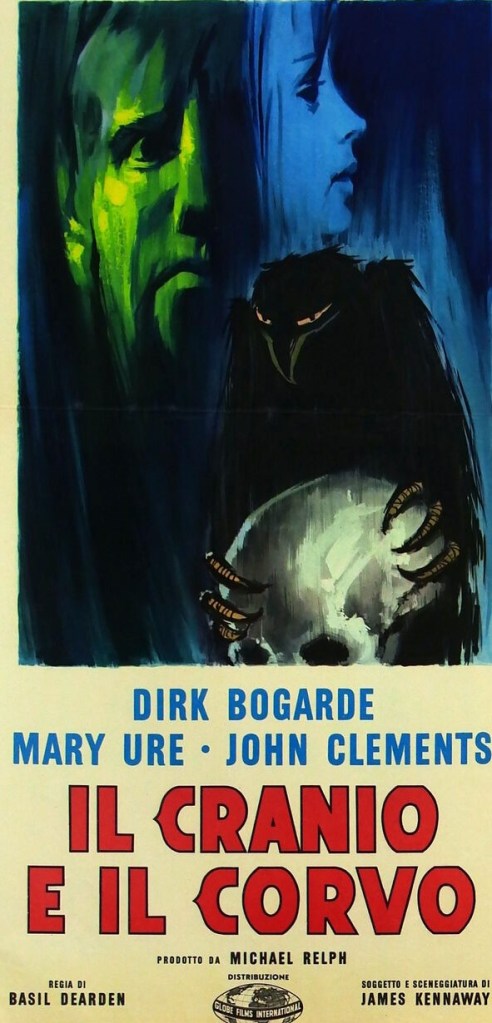

Dork Bogarde (Hot Enough for June, 1964) does this kind of role so well, the well-meaning person whose life is thrown into disarray. Mary Ure (Where Eagles Dare, 1968) is superb as the fun-loving wife, fighting for her husband, Michael Bryant excels as the sly friend, determined to win his wife by illicit means. Michael John Clemens only made two films this decade and his portrayal of the MI5 agent, as dispassionate as any scientist, putting country above individual, is almost as frightening as the experiment he provokes.

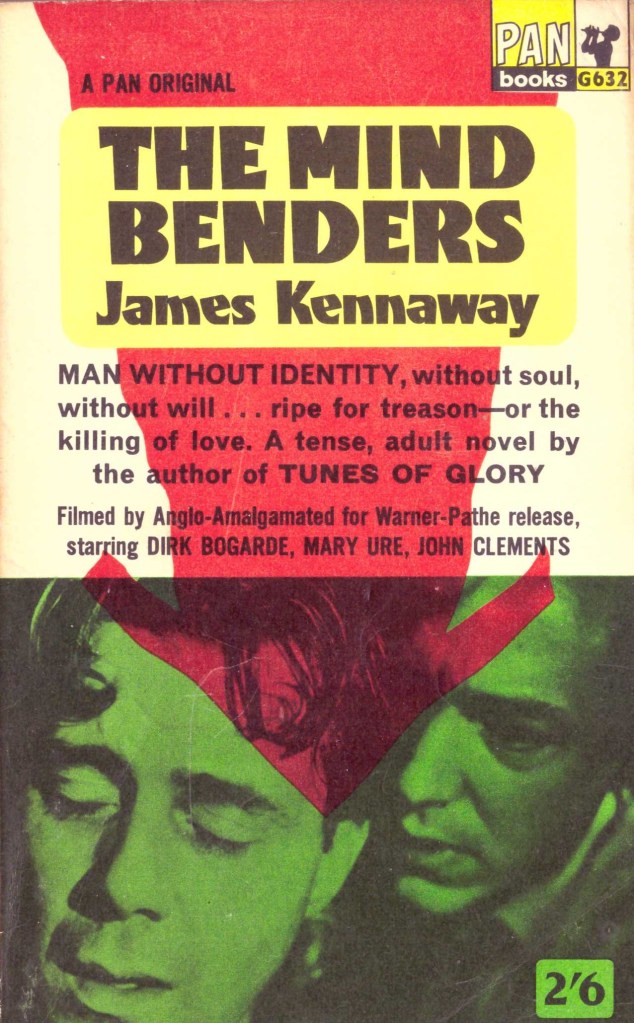

The idea came from an original screenplay by Scottish novelist James Kennaway (Tunes of Glory, 1960) who had come across the Canadian research. He was adept at placing stories within institutions in some respect with their own sacrosanct traditions and while the army barracks of Tunes of Glory could not be further removed from Oxford academe both reek of unchallenged hierarchy, of sacrifice to a cause.

Basil Dearden (Woman of Straw, 1964) directs this brilliantly, the attractive countryside location in contrast with the gloom of the experimental rooms, the warmth of a happy marriage evaporating in the face of insidious threat. He returned to the theme of identity in The Man Who Haunted Himself (1970).

This is one of these films that lives on in the mind long after the viewing has ceased and will strike a contemporary note where identity, and its shifting values, is such an issue.