I’ve marked this up since my previous viewing of it. And that’s an exceptionlly rare occurrence. What may not have suited the 1960s audience accustomed to standard boy-meets-girl boy-loses-girl even with whatever complications were available at the time, this should chime more with a contemporary audience seeking more reality and less glorification in a love story.

Not quite the Hollywood romance, too much bellyaching from the male for a start, and a couple of years before Love Story (1971) gave terminal illness a box office shot in the arm, but nonetheless very much an adult love affair and far from deserving a place in the top 50 worst films of all time.

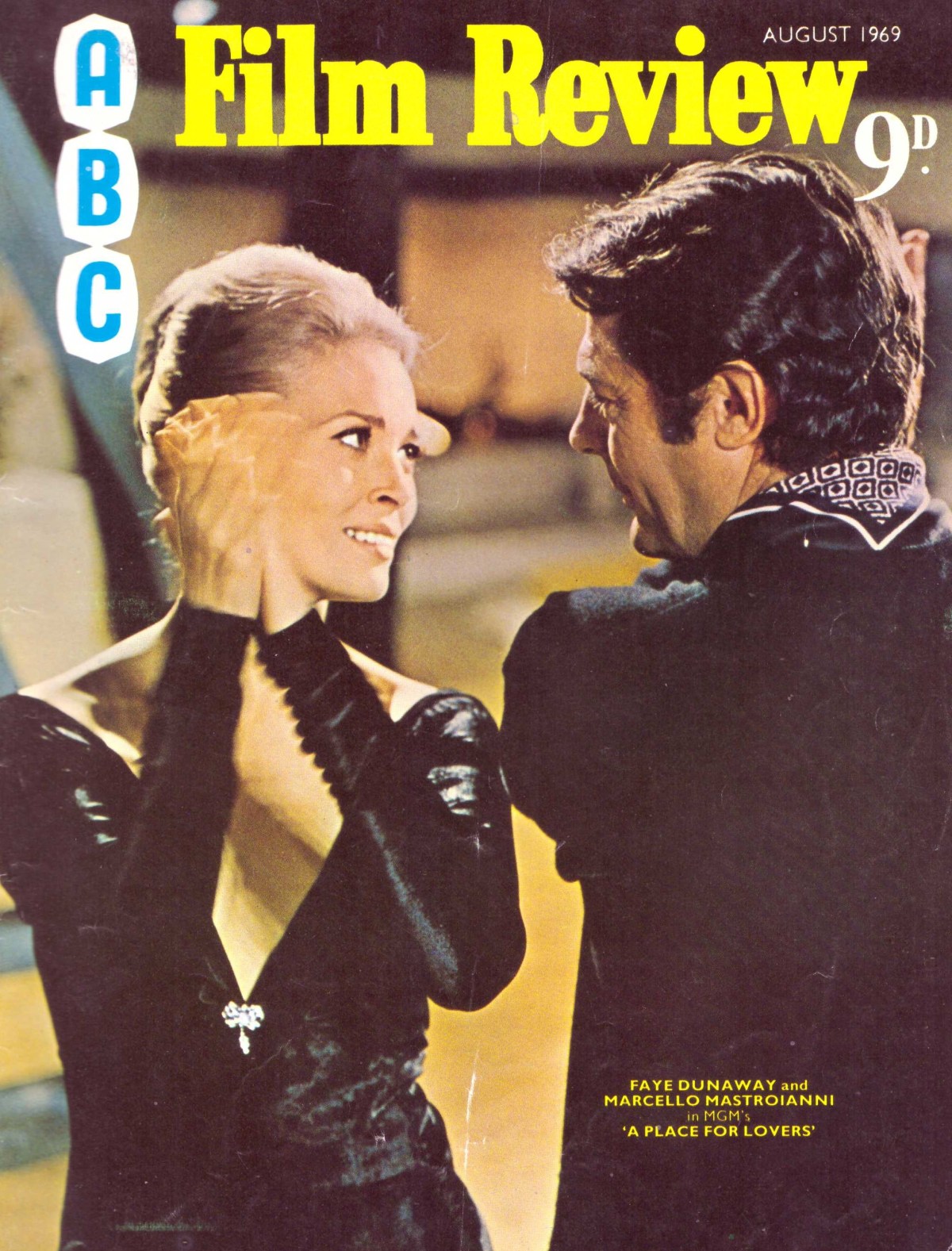

For a start director Vittorio De Sica plays around with audience expectations. This always has the feel of a romance that could end at any time, of characters not quite sure of the other person’s feelings, real love or just sex, the sense of not knowing where this could go, and of where, emotionally, they find themselves. And it begins with confusion, a blaring horn in the background, a close-up of Julia (Faye Dunaway), and then she jiggles around with some bricks in a wall before retrieving a key and finding her way inside a grand though modern Italian pallazo. You’ve no idea why she is here and I guess neither does she.

There’s been no meet-cute and there’s no real intimation of how the attraction began except, judging from a brief flashback, they must have bumped into each other at an airport. That’s my conclusion anyway because the details of the actual meeting are never clarified, like a lot of what subsequently goes on. She hides information from him, he does the same, so for a time feelings are not spelled out. It’s clandestine in all the wrong ways. There’s a separation, a distance, characters often seen in very long shot. Sometimes there are physical barriers between them, a high fence in one instance, as if true intimacy is impossible.

Still no sign of the man she has come to visit. She rescues a stray dog from the town dog collector. It’s an exceptionally grand house, classically designed, marble floors, paintings and artistic artefacts all over the place, but no clutter. When Valerio (Marcello Mastroianni) arrives – it’s his house – he checks the labels on her luggage, presumably finding out her full name, possibly her address, possibly accustomed to lovers providing false information on both counts. We learn he’s a safety-conscious racing driver, a man who requires barriers.

They are on a deadline already. She is only in Italy for a further two days. This is a lie. She has 10 days at her disposal but wants to set the pace, heat up the sexual atmosphere. They make love beside a lake. He takes her to dinner with friends where the entertainment is a lecture on sexual positions shown in art. But after someone suggests a game of what we would these days term speed-dating, he calls an end to the affair, jealous that she would consider spending any time in close proximity to another man.

So that’s it. Grand love affair dead and buried after just one day. Except she turns up next day at a practice at a racing circuit. After they reconcile, she watches in a car mirror as he makes a call in a phone box – speaking to his wife or another lover, we never find out, except her reaction explains it must be either.

There’s little of the sparkling dialog found in Hollywood romances, especially for audiences who grew up on the Tracy-Hepburn pictures, but she tells him that “if you put all the houses I have lived in you would make a good little town” and not just that she had lived a peripatetic lifestyle but that she also had six grandfathers so a rather fluid upbringing. She confesses now she has more time to spare, she just wanted him to ask for it, being stricken by her potential absence an indication in her eyes of true love.

So this is a fragile individual, her smile is always hesitant, external confidence hiding vulnerability. Her face is never flush with passion. When he asks why she never revealed her terminal illness, she replies, “I can’t take any more sad eyes.” There’s an ironic ending.

It is of course set against glorious backdrops but instead of letting the audience wallow in the love affair, as would be the Hollywood temptation, De Sica finds some way of undercutting it. Valerio is never quite sure of her and she is never quite sure of him. Their pasts remain hidden. Their lovemaking beside the lake is interrupted by a hunter bagging game. She coos over a baby only to discover it has an ugly father. She drives too fast even with a racing driver in the passenger seat and she clearly has suicidal tendencies, the love affair almost a salve for her despair.

We could have been presented with the suave charming Marcello Mastroianni (La Dolce Vita, 1960) cliché from a dozen Italian films, but instead he is often jealous, annoyed, real. Faye Dunaway (Bonnie and Clyde, 1967) plays a character who never knows where she stands with her emotions, accepting her fate one moment, determined to end her life the next, and yet still time to dally in a love affair that of course can have no future.

Vittorio De Sica (Two Women, 1960) has fashioned a picture that is neither uplifting nor downhearted, a love affair that lives just for the moment, but with implied complications that could at any moment wreck it, a romance always teetering on the edge.

I’ve no idea what compelled Harry Medved to include this in The Fifty Worst Films of All Time, published in 1978, but you might easily question his judgement on discovering that his list includes Sergei Eisenstein epic Ivan the Terrible, Alain Resnais’s hypnotic Last Year at Marienbad, Otto Preminger’s Hurry Sundown, Alfred Hitchcock’s Jamaica Inn and even such passable entertainments as The Omen.

Maybe you’ve been put off giving this a whirl thanks to the Medved seal of disapproval. A Place for Lovers is not the greatest film ever made, but it’s certainly far from the worst, two striking actors and a director who could never make a terrible picture make sure of that. And, as I mentioned, exerts greater appeal for the contemporary viewer.

No DVD available so you will need to check out Ebay or streaming.