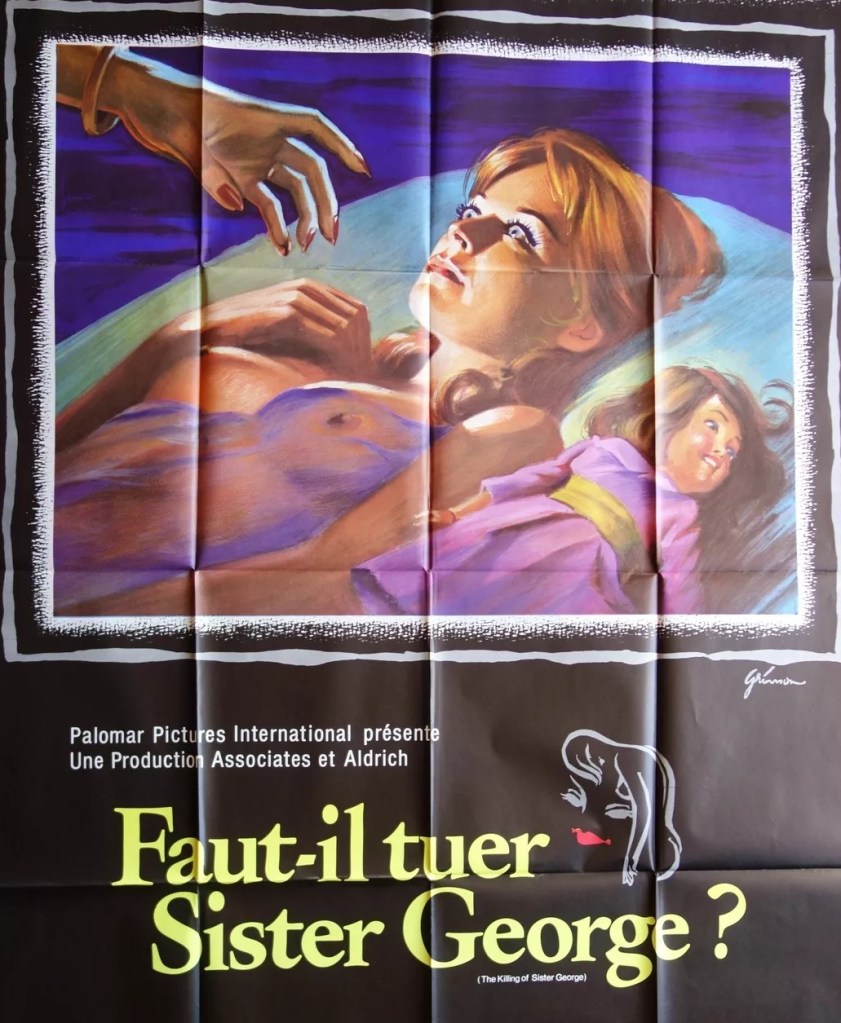

Somewhere between camp classic, hilarious comedy and bitchiness-on-speed, loaded down with a May-December narrative, too much of the genuine soap opera element of the filming of a soap opera but lifted up by some very touching moments. This started life as a black comedy and its stage antecedents are only too obvious, many scenes running way too long for a movie, and in the unlikely hands of director Robert Aldrich – at this point best known for male actioner The Dirty Dozen (1967) rather than the equally bitchy Whatever Happened to Baby Jane (1962) – asks audiences to ingest a great deal more seriousness.

The sex scene was so shocking in its day that, in the reformed U.S. censorship system, earned one of the first mainstream X-certificates, thus torpedoing its box office potential as newspapers routinely refused to accept adverts for such. Yet while it is tender, and to some extent galvanized by the astonishment of older lesbian Mercy Croft (Coral Browne), a high-ranking television executive, at having such a young and adorable lover as Alice (Susannah York), it is sabotaged by Alice’s gurning.

Whereas Beryl Reid’s performance as aging soap opera actress June (aka Sister George) about to be cut adrift by the television production which has made her name is pretty much spot on as a drunken, insecure, needy, dominant, older lover. Susannah York (They Shoot Horses, Don’t They, 1969) just seems out of control as the bonkers dumb blonde. While same sex relationships between men had only just become legal in England, and the specter of blackmail, public scandal or imprisonment that had hung over many generations now removed, there had never been a correlative for women. Though a newspaper headline might well kill a career.

The best sequence in terms of the harmonious gay relationship comes in the gay club where women hold each other for a slow dance and it seems so normal and touching. Of course, relationships, straight or gay, don’t necessarily run smoothly, but the longstanding affair between June and Alice belongs to the Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf (1966) playbook. Alice may well be a gold-digger for all she does, but since the May-December aspect of male-female relationships was a standard Hollywood trope it seems fair enough to apply the same rationale to a single-sex partnership.

There’s some uncomfortable sadism when, as punishment for mild misdemeanor, Alice is forced to eat a cigar butt and told in no uncertain terms just how stupid she is. There had been a recent rash of on-set bitchiness, star tantrums and studio power struggles from pictures like The Carpetbaggers (1964), Harlow (1965), Inside Daisy Clover (1965), The Oscar (1966) and Aldrich’s own The Legend of Lylah Clare (1968), so none of production shenanigans bring anything new to the table.

However, when June lets rip, embarrassing management or forcing her fellow actors to laugh during a tragic scene, this is comedy gold. Her alcohol intake and arrogance aside, it seems a step too far for June to attempt to sexually assault two nuns in a taxi – this unseen sequence key to her downfall. You might be inclined to question how Alice came into the sexual orbit of June and Mercy in the first place, and wonder if the two older women are not guilty of what would be termed these days inappropriate behavior in taking advantage of clearly a vulnerable young woman.

Beryl Reid (The Assassination Bureau, 1969) walks a fine line between self-indulgence and character insight. I felt Susannah York’s over-acting got in the way. The tight-lipped Coral Brown (The Legend of Lylah Clare) was too close to the cliché for my liking.

Robert Aldrich just about gets away with it. Lukas Heller (The Dirty Dozen) adapted Frank Marcus’s play.