MGM wasn’t the first studio to hit upon the idea of re-editing episodes of a television series into a movie for cinema release. Small-screen The Lone Ranger had spawned The Legend of the Lone Ranger (1952) and Disney had stitched together episodes from its Davy Crockett franchise to create Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier (1955) and Davy Crockett and the River Pirates (1955). The Challenge for Rin Tin Tin (1957) derived from The Adventures of Rin Tin Tin, Frontier Rangers (1959) born out of Northwest Passage, the Texas John Slaughter series the basis for five movies shown between 1960 and 1962, Crimebusters (1962) originated from Cain’s Hundred and Lassie’s Great Adventure (1963) from five episodes of the eponymous series.

But all these movies had one major disadvantage. Like their source material, they appeared in black-and-white. The Disney pair mined some box office gold, but primarily as matinee material. The rest were fillers, scheduled for the bottom half of a double bill and aimed at suburban and small-town cinemas and drive-ins desperate for anything to fill out a program. And all were nothing cruder than editing two or more episodes together to make a feature film.

MGM took a different approach. Instead of merging two different episodes, albeit starring the same stars, the studio decided to take one episode and expand it, filling out the story with subplots and extra characters and spicing up proceedings with levels of sex and violence that would not be tolerated on mainstream television. As important, it would be shot in color to make it stand out from the television series being shown in black-and-white.

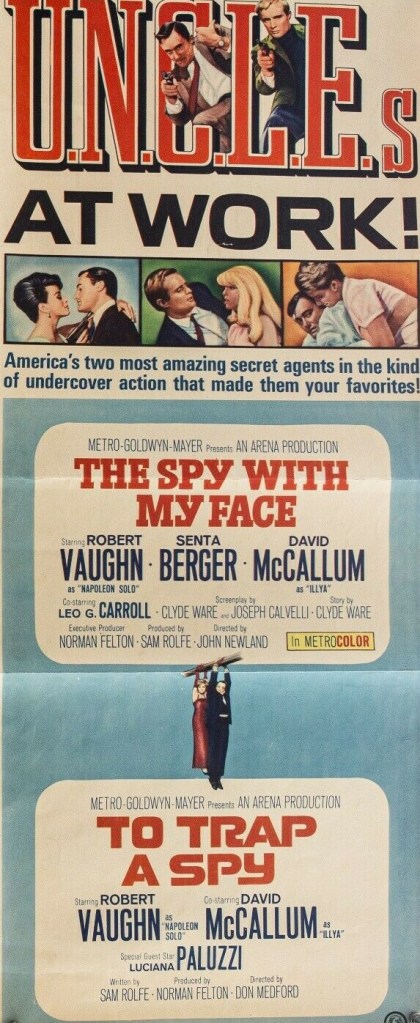

First picture in the trial scheme was To Trap a Spy (changed form the initial To Catch a Spy), an expanded version of the television pilot known as The Vulcan Affair, and as well as series leads Robert Vaughn (The Magnificent Seven, 1960) and David McCallum (The Great Escape, 1963) toplined future Bond femme fatale Luciana Paluzzi (Thunderball, 1965). A second movie was culled from The Double Affair which had been screened on November 17, 1964, with an European star with a considerable pedigree in Senta Berger (Major Dundee, 1965).

Since MGM had no idea whether the spy series, launched in the U.S. on NBC on 22 September 1964, would catch on abroad, where in any case stations paid comparatively little to screen top American shows, its initial idea was to release films only for the foreign market.

In fact, the studio didn’t wait to see if the BBC could make a hit out of the debuting The Man from U.N.C.L.E. series and shunted out To Trap a Spy before the series even screened in Britain. And lacking momentum from television, it went out as the support on the ABC circuit in Britain to The Americanization of Emily (1965) starring Julie Andrews and James Garner.

At that time, the ABC chain was not beholden to the double bill idea. In fact, more than half the annual weekly releases went out as solo affairs. A double bill was more likely to suggest that there were doubts over the pulling power of the main film. There was no way of judging the box office appeal of any film put out in the lower half of a double bill.

The odd thing was that if MGM had held off pressing the button on the circuit release, To Trap a Spy would have demonstrated box office success. At the same time as the double bill was simultaneously released at nationwide first run theaters, To Trap a Spy opened in London’s West End in May 1965 at the 529-seat Ritz and delivered the best business MGM had enjoyed there for two years. It returned to the 556-seat Studio One, also in the West end, in October that year as the top attraction in a double bill that included Glenn Ford-Henry Ford western The Rounders (1965) and in its fifth week took in an excellent $5,600 and a few weeks later shifted back to the Ritz.

Between released the first and second Uncle pictures, MGM had launched a major marketing campaign on the back of the launch of the series on BBC. One marketing gimmick, inviting the audience to write in for The Man from U.N.C.L.E. certificates, brought in over half a million applications. MGM splashed out $85,000 marketing The Spy with My Face (1965). Again, the movie went out in an ABC circuit release – in July 1965 – as part of a double bill, with Son of a Gunfighter (1965), but this time the Uncle film topped the bill. Launched in the West End at the much larger 1,330-seat Empire it took $22,000 in its opening week. Nationally, “it was far and away above average for a top-grossing picture in the UK.”

To Trap A Spy and The Spy with My Face each grossed $2 million in the UK market. By January 1996, a third Uncle film had launched in the British market, One Spy Too Many, based on the two-episode Alexander the Great Affair which had screened in America in September 1965. This time MGM held off from ABC circuit release until mid-February until One Spy Too Many had cleaned up in January in the West End, $25,000 at the Empire, helped along by a Xmas merchandizing bonanza that saw the country flooded with memorabilia, paperbacks, three singles and an album. It broke studio records in 91 of the 125 situations it first played.

The success of the first pair pointed up the potential U.S. box office from these featurized episodes and MGM put together the double bill The Spy with My Face/To Trap a Spy on the assumption that the films at the very least would pick up business outside first run venues where bigger-budgeted pictures dominated and provide respite for showcase (wide release) theaters, drive-ins and small cinemas suffering from product shortage. The bigger a hit a movie became, whether roadshow or not, the longer it took to move down the food chain.

MGM was also inspired by the merchandizing boom generated by the television. A toy gun was well on its way to notching up sales of two million, and there were in addition, games, puzzles, trading cards, costumes and masks and chewing gum.

The MGM was entering a very crowded espionage market. Not only had Thunderball taken the top off the box office with an explosive debut in Xmas 1965, but any new entrant into the field in 1966 would come up against such spy behemoths as Columbia’s Our Man Flint (1966) and The Silencers (1966) from Twentieth Century Fox as well as more offbeat spy numbers like Paramount’s The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1965) and other pictures aiming for a slice of the cake like Where the Spies Are (1966) with David Niven and That Man in Istanbul (1965).

Variety magazine was sniffy about the double bill’s prospects – “for the least discriminating audiences” was its take on To Trap a Spy although Box Office deemed it “far better story-wise” than The Spy with My Face.

The Spy with My Face/To Trap a Spy gained surprising traction in first run, even though MGM was demanding a 50 per cent share of the box office. In some cities it ran smack bang into the openings of one or other of the biggies while Thunderball played for months on end. Even so, the results were surprisingly good. Leading the single cinema first run bows was $24,000 – equivalent to $214,000 now – in Chicago (and a second week of $18,000). Boston audiences delivered $16,000 (plus $11,000 second week), Detroit $18,000 (and $12,000). It ran for three weeks in Washington D.C., Philadelphia and Providence and two weeks in St Louis, Buffalo, St Louis, San Francisco and Cleveland.

There were one-week bookings at other major cities like Seattle, Pittsburgh, Minneapolis and Cincinnati. Except in Portland (“drab” first week and “dull” the second) and Seattle (“okay”) the box office verdict varied from “potent,” “virile” and “sock” to “nice,” “fine,” and “pleasant.” Box Office magazine reckoned that in Hartford the duo produced revenues over three times the average and in Memphis twice the average.

Following first run, it would go into wider breaks in these various cities. Some cities ignored first run and opted for a straight “showcase” (wide release) bow, New York leading the way with $104,000 – $928,000 equivalent today – from 25 cinemas, Kansas City bringing in $35,000 from 10 in week one and $25,000 from 10 in week two, and Baltimore good for $40,000 from 18. In new England cinemas and drive-ins united for a multiple run release hat “rang up some of the briskest business of the winter months despite the adverse weather conditions.” The only downside was the Pacific chain of drive-ins refusing to show the double bill on the grounds that previous experience of showing movies adapted from television series had “brought patron beefs” and that its own tests had not worked.

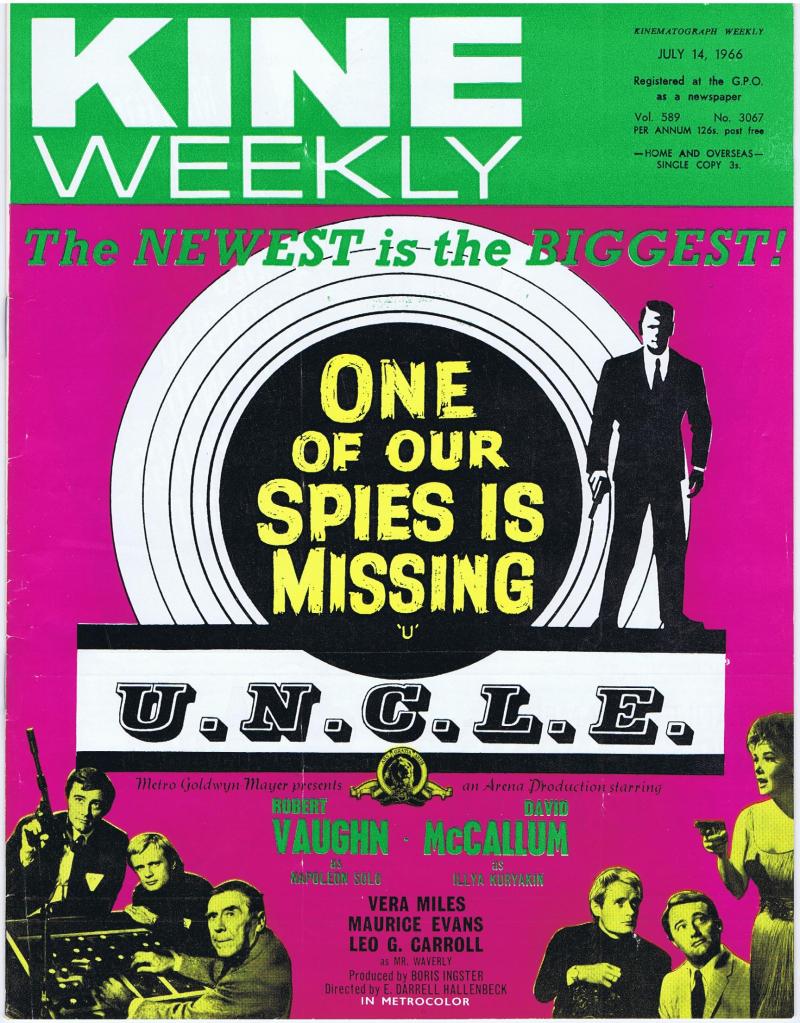

Even when The Man from U.N.C.L.E. series ended after three-and-a-half seasons, MGM continued bringing out movies, eventually totalling eight in all. The others were: One of Our Spies Is Missing (1966), The Spy in the Green Hat (1966), The Karate Killers (1967), The Helicopter Spies (1968) and How to Steal the World (1968).

Towards the end of the decade the Easy Rider (1969) phenomenon prompted a brief vogue for box office analysts to point to low-budget pictures generating the biggest profit. Nobody tended to include the first three Uncle films in this equation regardless of the fact that, costing an original $200,000 per episode plus extra for reshoots and editing, they were, on a profit-to-cost basis, extraordinarily successful, easily bringing home revenues in the region to 10-15 times their budgets.

SOURCES: Allen Eyles, ABC: The First Name in Entertainment (CTA, 1993), p123; “Another Uncle Sequel As O’Seas Theatrical,” Variety, September 23, 1964, p79; “Uncle Gets 3rd Whirl As O’seas Feature,” Variety, January 27, 1965, p26; “International Soundtrack,” Variety, May 26, 1965, p26; “Toys from Uncle,” Variety, June 30, 1965, p42; “Uncle Stunt in London Is Metro Hit,” Variety, December 8, 1965, p23; “Metro Sees Uncle TV Stanzas As B.O. Kin to James Bond in Theaters,” Variety, February 2, 1966, p1; Review, Variety, February 16, 1966, p18; Review, Box Office, February 21, 1966, pB11; “Box Office Barometer,” Box Office, March 14, 1966, p22; “One Spy Looms MGM Leader in Britain,” Variety, March 20, 1966, p29; “Drive-Ins in New England Preparing To Solve Springtime Problems,” Box Office, March 21, 1966, pNE4; “Pacific Prefers Not To Follow Video,” Variety, April 20, 1966, p24; “Box Office Barometer,” Box Office, June 20, 1966, p14; “How Uncle in Great Britain Clicked Via Tie-Ups with Tele,” Variety, June 22, 1966, p17; “Uncle TV Conversions Boffo at B.O. Theatrically O’Seas,” Variety, March 20, 1968, p4; Box Office figures taken from the weekly edition of Variety in the “Picture Grosses” section on the following dates: in 1965 on November 10 and December 8, in 1966 from February 2 until June 1; and August 18, 1966.