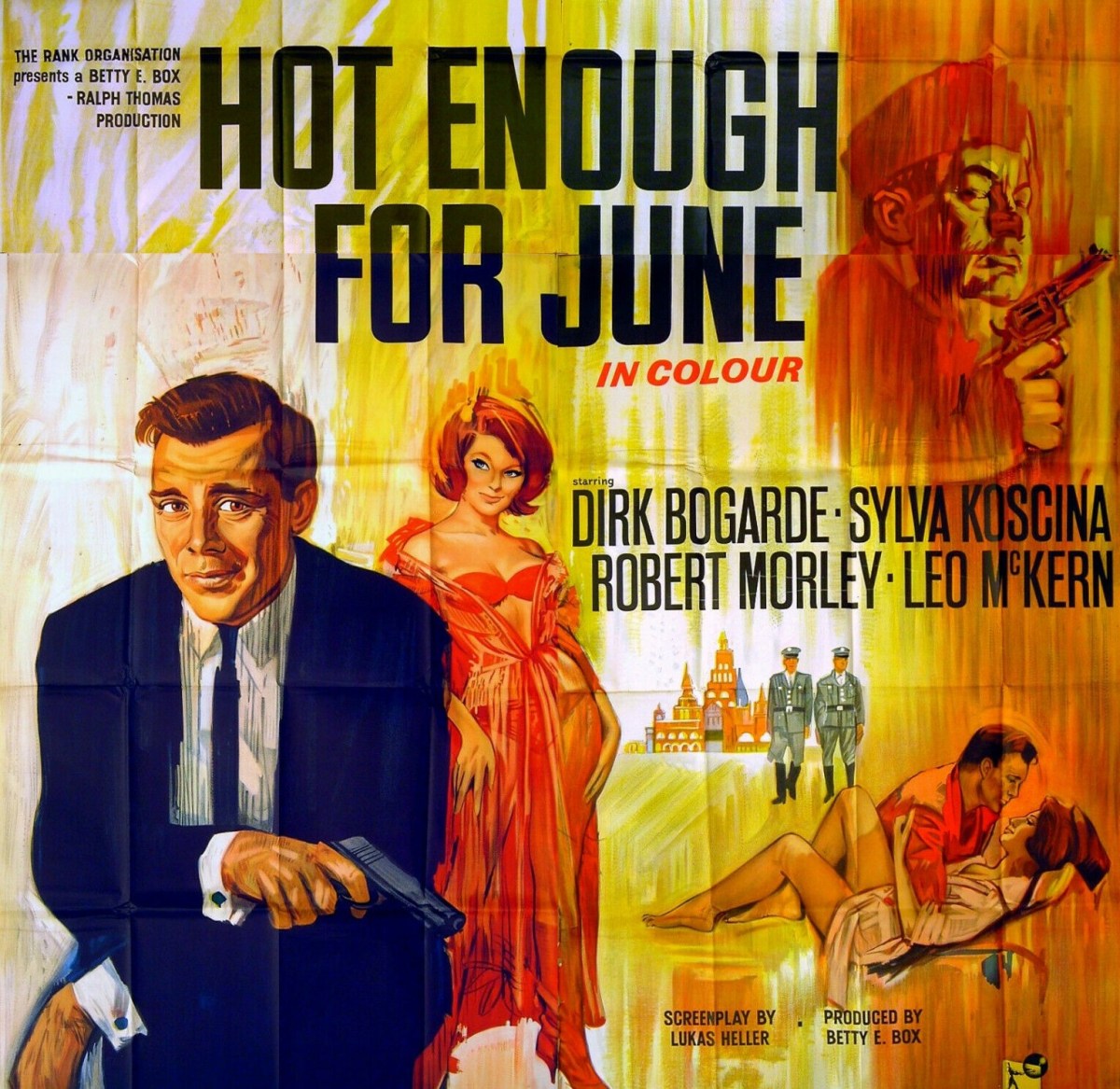

Thanks to his language skills unemployed wannabe writer Nicholas (Dirk Bogarde) is recruited as a trainee executive on a too-good-to-be-true job visiting a Czech glass factory only to discover that while engaged on what appears a harmless piece of industrial espionage is in fact considerably more serious. Complications arise when he falls in love with his chauffeur Vlasta (Sylva Koscina) whose father, Simenova (Leo McKern), is head of the Czech secret police.

Eventually, it dawns on Nicholas that he is in the employ of the British secret service headed by Colonel Cunliffe (Robert Morley). Soon he is on the run. Adopting a variety of disguises including waiter, Bavarian villager and milkman, he evades capture and makes a pact with Vlasta that neither of them will participate in espionage activities.

A chunk of the comedy arises from misunderstandings, Iron Curtain paranoia, the destruction of indestructible glass, password complications, Nicholas’s contact turning out to be a washroom attendant, and from the essentially indolent Nicholas being forced into uncharacteristic action. Soon he is adopting the kind of ruses a secret agent would invent to outwit the opposition, including burning the hand of a man with his cigarette and stealing a milk cart.

The romance is believable enough and Vlasta has the cunning to shake off the secret agent shadowing her, although the ending is unbelievable and might have been stolen from a completely different soppy picture. Although Nicholas is clearly in harm’s way several times that is somewhat undercut by the espionage at a higher level being presented as a gentleman’s game.

There are unnecessary nods to 007 and the kind of gadgets essential to Bond films, although none come Nicholas’s way. But these attempts to modernise what is otherwise an old-fashioned comedy largely fail. Taking a middle ground in comedy rarely works. You have to go for laughs rather than plod around hoping they will miraculously appear. And in fact the comedy is redundant in a plot – innocent caught up in nefarious world – that has sufficient story and interesting enough characters to work.

That the movie is in any way a success owes everything to the casting. Dirk Bogarde, though well into his 40s, still can carry off a character more than a decade younger. He can turn on the diffidence with the flicker of an eyelash. And yet can call on inner strength if required. He is the ideal foil for light comedy, having made his bones in Doctor in the House (1954), reprising the character for Doctor in Distress (1963) and dipped in and out of serious drama such as Victim (1961) and the acclaimed The Servant (1964), released just before this.

In some respects it seems as if two different pictures are passing each other in the night. The Bogarde section, excepting some comedy of misfortune, is played for real while in the background is a bit of a spoof on the espionage drama.

Sylva Koscina (The Secret War of Harry Frigg, 1968) is excellent as the beauty who betrays her country for love. Robert Morley (Topkapi, 1964) and Leo McKern (Assignment K, 1968), although in on the joke, are nonetheless convincing as the secret service bosses. Look out for a host of lesser names in bit parts including Roger Delgado (The Running Man, 1963), Noel Harrison (The Girl from U.N.C.L.E. 1966-1967), Richard Pasco (The Gorgon, 1964) and stars of long-running British television comedies John Le Mesurier, Derek Fowlds and Derek Nimmo.

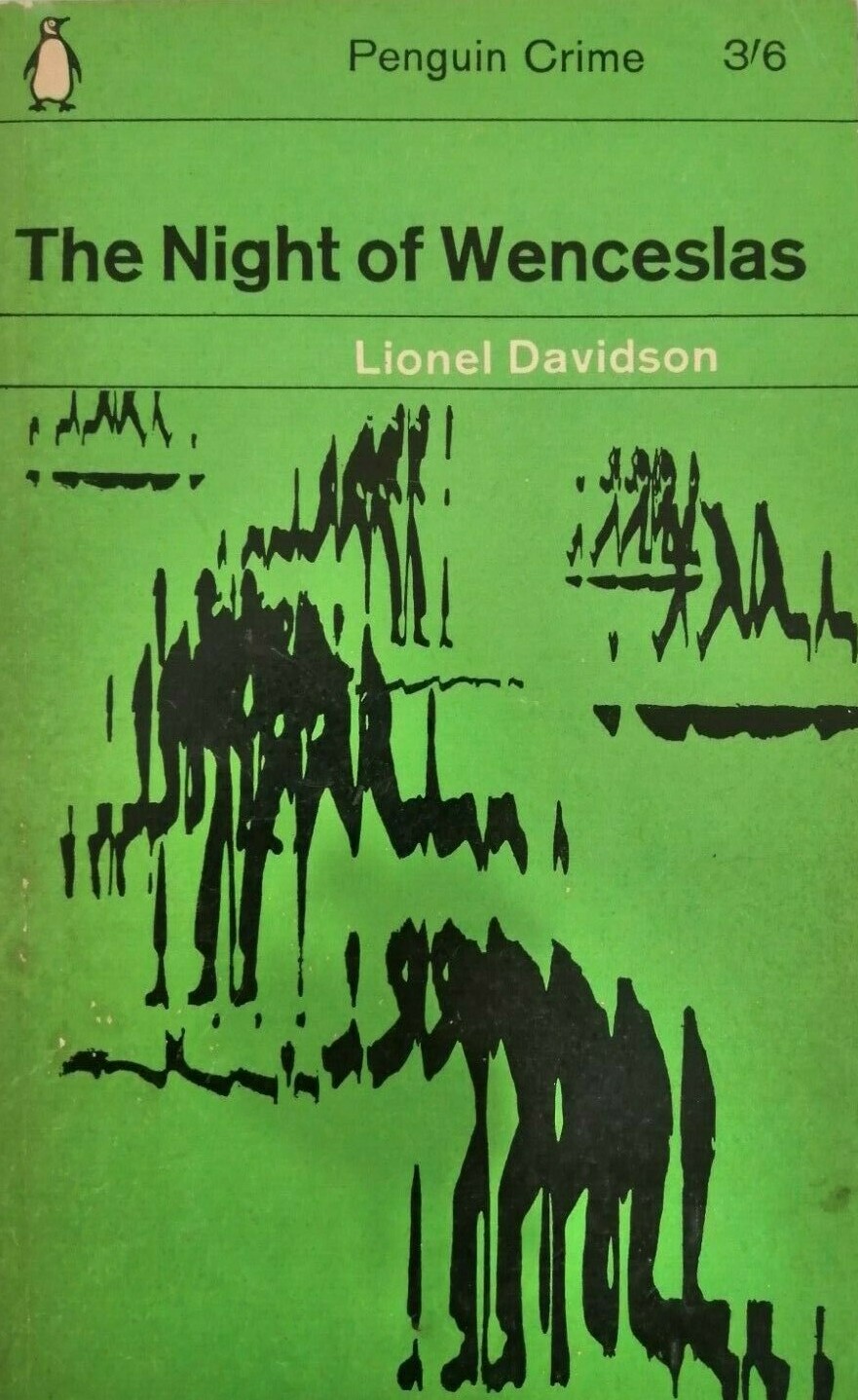

This was the eighth partnership between director Ralph Thomas and Dirk Bogarde, four in the Doctor series but also three serious dramas in Campbell’s Kingdom (1957), A Tale of Two Cities (1958) and The Wind Cannot Read (1958). In themselves the comedies and the dramas were successful, but mixing the two, as here, less so. Written by Lukas Heller (Flight of the Phoenix, 1965) from the bestseller by Lionel Davidson.

American distributors were less keen on this picture and it was heavily cut for U.S. release and retitled Agent 8¾ presumably in an effort to cash in on the James Bond phenomenon. I’ve no idea what was lost – or perhaps what was gained – by the editing.

The end result of the original version is a pleasant enough diversion but not enough of the one and not enough of the other to really stick in the mind.

Should you be interested in how the book was translated into the film, there’s another article here covering that. Link below.