Class A Trash. Adaptation of Harold Robbins (Nevada Smith, 1966) bestseller goes straight to the top of the heap in the So-Bad- It’s-Good category. Only Alan Badel (Arabesque, 1966) as a double-dealing revolutionary comes out of this with any honors.

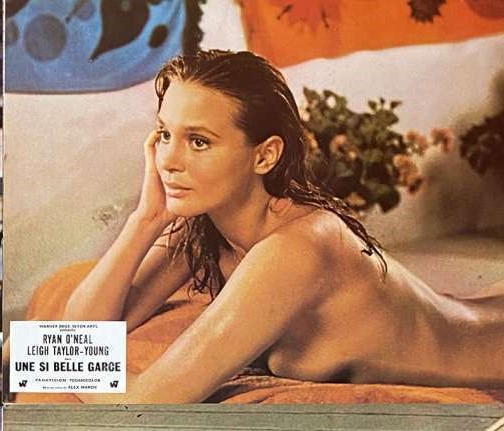

The likes of Candice Bergen (Soldier Blue, 1970), Rossano Brazzi (Rome Adventure/Lovers Must Learn, 1962), double Oscar-winner Olivia de Havilland (Hush, Hush, Sweet Charlotte, 1964), Leigh Taylor-Young (The Big Bounce, 1969) and Ernest Borgnine (The Wild Bunch, 1969) must have wondered how they were talked into this.

And director Lewis Gilbert (Loss of Innocence/The Greengage Summer, 1961) must have wondered how he talked himself into recruiting unknown Yugoslavian Bekim Fehmiu (The Deserter/The Devil’s Backbone, 1970), nobody’s idea of a suave lothario, for the lead.

One of the taglines was “Nothing has been left out” and that’s to the movie’s detriment because it’s overloaded with sex, violence, more sex, more violence, in among a narrative that races from South American revolution (in the fictional country of Corteguay) through the European jet set, fashion, polo, fast cars, orgies, and back again with revenge always high on the agenda. At close on three hours, it piles melodrama on top of melodrama with characters who infuriatingly fail to come to life.

Sensitivity is hardly going to be in order for Dax (Bekin Fehmiu) who, as a child after watching his family slaughtered and mother raped, makes his bones as a one-man firing squad, machine-gunning down the murderers. From there it’s a hop-skip-and-jump to life as the son of ambassador Jaime (Fernando Rey) in Rome where he belongs to an indulgent aristocracy who play polo, race cars along hairpin bends, swap girlfriends and, given the opportunity, make love at midnight beside the swimming pool.

His fortunes take a turn for the worse when his father backs the wrong horse, the rebel El Condor (Jorge Martinez de Hoyos) in Corteguay, and is killed by the dictator Rojo (Alan Badel). In between an affair with childhood sweetheart Amparo (Leigh Taylor Young), life as a gigolo and cynical marriage to millionairess Sue Ann (Candice Bergen), Dax takes up the rebel cause, initially foolish enough to fall for Rojo’s promises which results in the death of El Condor, and then to join the rebels.

But mostly it’s blood, sex, betrayal and revenge. Anyone Dax befriends is liable to face a death sentence. He only has to look at a woman and they are stripping off. It’s a heady mess. It might have worked if the audience could rustle up some sympathy for Dax, especially as he was entitled to feel vulnerable after his childhood experiences. But he just comes across as arrogant and the film-makers as even more arrogant in assuming that because women fall at his feet that must mean he had bucketloads of charm rather than that was what it said in the script. He’s fine as the thug but not convincing as a lover.

Excepting Badel, the best performances in a male-centric sexist movie come from women, those left in Dax’s wake, particularly Candice Bergen as the lovelorn wife and Olivia De Havilland as the wealthy older woman who funds his lifestyle, aware that at any moment he will leave her for a younger, richer, model. Lewis Gilbert is at his best when he lets female emotion take over, not necessarily wordy intense scenes, because Bergen and De Havilland can accomplish a great deal in a look.

The rest of it looks like someone has thrown millions at a B-picture and positioned every character so that they have nowhere else to go but the cliché.

By this point, Hollywood had played canny with Harold Robbins, toning down the writer’s worst excesses and employing name directors to turn dire material into solid entertainment. Edward Dmytryk (Mirage, 1965) had worked wonders with The Carpetbaggers (1964), whose inherent salaciousness was held in check by the censor and made believable by characters played by George Peppard (Pendulum, 1969), Alan Ladd (Shane, 1953) and Caroll Baker (Station Six Sahara, 1963). Bette Davis and Susan Hayward contrived to turn Where Love Has Gone (1964) into a decent drama. Even Stiletto (1969), in low-budget fashion, managed to toe the line between action and drama.

But here it feels as if all Harold Robbins hell has been let loose. Rather than reining in the writer, it’s as if exploitation was the only perspective. Blame Lewis Gilbert, director, and along with Michael Hastings (The Nightcomers, 1971) in his movie debut, also the screenwriter for the end result.

On the other hand, if you can leave your critical faculties at the door, you might well enjoy how utterly bad a glossy picture can be.