Lewis Gilbert was on a career high. After a string of flops – Loss of Innocence/The Greengage Summer (1961) and The 7th Dawn (1964) – he had bounced back with the critically-acclaimed and Oscar-nominated box office hit Alfie (1965), cementing his commercial standing with You Only Live Twice (1967).

Next up was Oliver!, the adaptation of the Lionel Bart musical. Gilbert had bought the rights to the songs after its debut in 1960 – from British singer Max Bygraves of all people who owned a music publishing company – but was prevented from filming it until it had completed its Broadway and London runs, as was standard with hit musicals. In the wake of Alfie he was prepping the musical, turning down the likes of Richard Burton and being forced to consider Julie Andrews and Dick Van Dyke for the leading roles. But he had also signed a very beneficial contract with Paramount chief Charles Bluhdorn.

Gilbert took it as read that he had Bluhdorn’s agreement to make Oliver! first. By now, he had co-written the script with Vernon Harris, was in the process of finalizing costumes, choreography, musical arrangements and sets, and was all set to make the movie “he had been born to direct.”

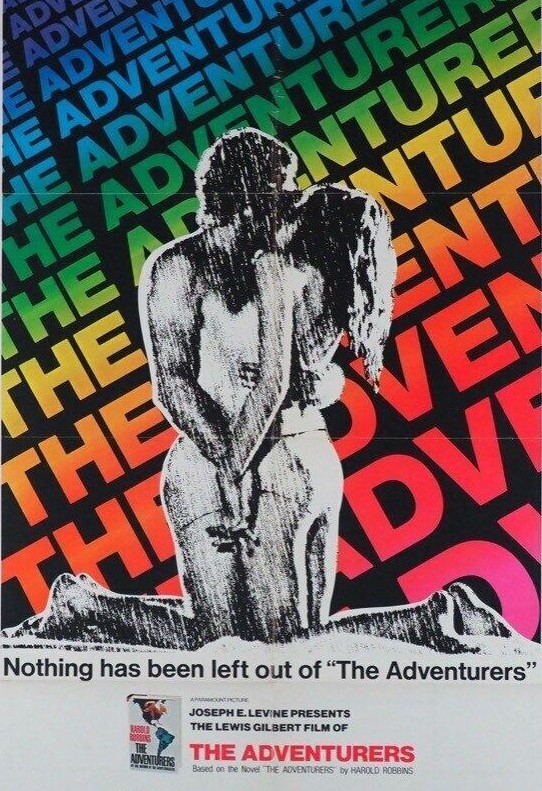

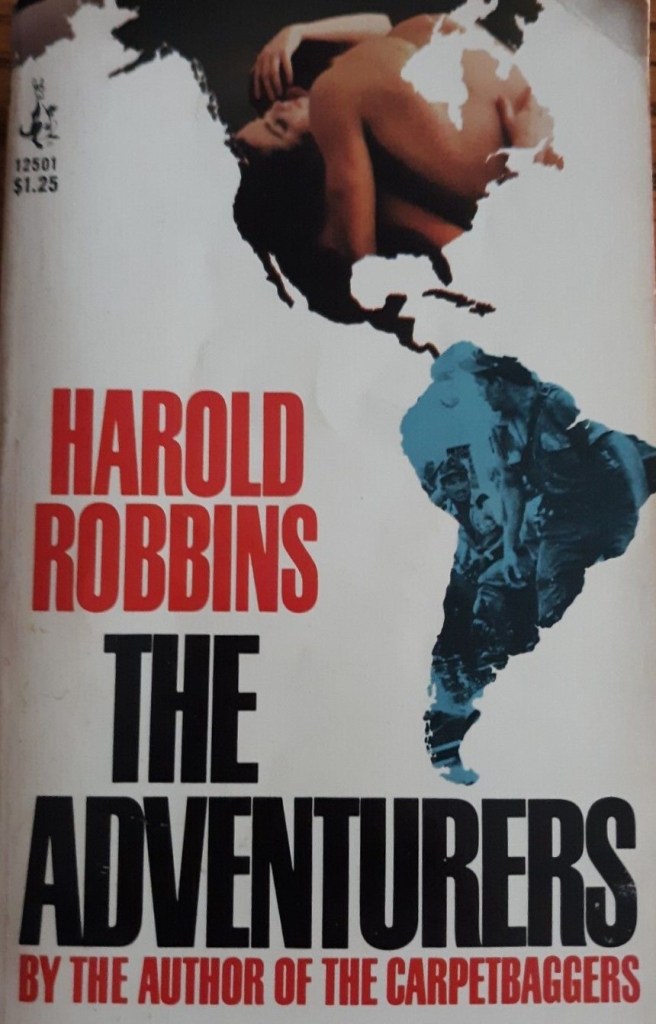

Bluhdorn had other ideas. He had taken over Harold Robbins’ big, brash bestseller The Adventurers from Joseph E. Levine who had bought the rights for $1 million in 1963. A script by John Michael Hayes (Nevada Smith, 1966) had been scrapped, but Bluhdorn had made little headway and with the studio under the cosh after investing too much in flops, was desperate for a safe pair of hands. Gilbert soon realised that in Hollywood a person’s word was not their bond. Bluhdorn knew all about contracts and had signed an unhelpful one himself, which set him a tight deadline to deliver a picture.

Gilbert threw away the unwieldy screenplay written by Robbins and settled down with playwright Michael Hastings (The Nightcomers, 1971) to condense the equally unwieldy novel down to a two-hour running time. But once again Bluhdorn had other ideas. After Gilbert had begun pruning, Bluhdorn demanded a three-hour roadshow. Then he sprung another surprise. “Stars are out of date,” he announced, “We don’t need them.”

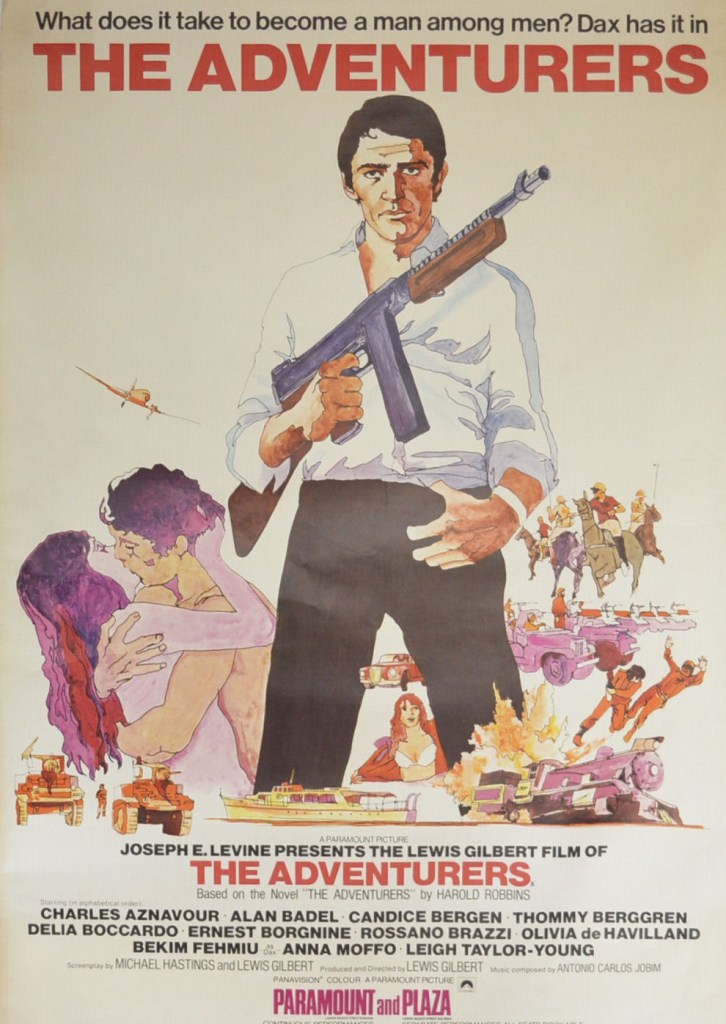

That was a blow to Gilbert who had envisioned Alain Delon (Once a Thief, 1965) for the leading role of a cold-hearted but suave playboy. The actor’s personal reputation for squiring many of the most beautiful women in France meant he was viewed by an audience as a man with abundant charm. And his films roles had proved he could easily pass for cold-hearted. So it was with reservations that Gilbert turned instead to unknown Bekim Fehmiu from Bosnia Herzegovina who had attracted critical plaudits for I Even Met Happy Gypsies (1967), winner of the Palme D’Or at Cannes.

Initially, production was going to be split between Paris and Colombia until the 1968 riots put the French capital out of commission. French actors like Louis Jourdan (Can-Can, 1960) already cast were dumped. Rome proved a good substitute, but the four main studios were already occupied, forcing the production to take whatever space remained available in all of them. Venice and New York City were also briefly used.

To speed up production, and switch the locales from France to Italy, Gilbert employed other writers, Clive Exton (10 Rillington Place, 1971) and Jack Russell (Friends, 1971), as well as Hastings, each working independently of the other, the whole being coordinated by Vernon Harris.

The cast mixed experience with newcomers. As well as Fehmiu, Gilbert recruited relative beginners Candice Bergen (The Magus, 1968) in her fifth film, Swede Thommy Bergrenn (Elvira Madigan, 1967) making his Hollywood debut, Leigh Taylor-Young, only known at this point for her debut I Love You, Alice B. Toklas (1968) and Italian Delia Boccardo, leading lady in Inspector Clouseau (1968).

Heading up the veterans were double Oscar-winner Olivia De Havilland, Oscar-winner Ernest Borgnine, a supporting player in items like Ice Station Zebra (1968), and Italian Rossano Brazzi (Krakatoa, East of Java, 1968) who had fallen a long way down the credits since the heights of South Pacific (1958). As makeweights – essential for an “international all-star cast” – were Spaniard Fernando Rey (Villa Rides, 1968), French singer Charles Aznavour and British character actor Alan Badel (Arabesque, 1966).

At the end of the Rome shoot, Gilbert declared himself “surprisingly optimistic.” Colombia killed that off. The only way to reach many remote locales was on horseback. Actors whose contracts dictated travel by luxury transport found their vehicles could not negotiate steep narrow pathways. Six thousand extras recruited from dozens of small villages had to get up at 3am to walk, in the absence of transport and roads, to a main location in a small town where catering for such numbers was in itself a major logistical exercise.

Accommodation for the stars was difficult to find. One location only had one hotel and that with only four rooms. Gilbert tore ligaments in his foot, making walking impossible. He directed all future outdoor scenes atop a horse like a “great old-time director in the days of silent films.”

The South American scenes, pivoting on blood-thirsty violence and revenge, were at odds with the ones filmed in Rome that showcased high society and seductive sex. The two halves were an uneasy mix at best. And the actor who was meant to bind them was not working out. As the movie wore on, Gilbert realized Fehmiu was miscast. While Fehmiu could match Delon’s exploits with women, Brigitte Bardot reputedly among his conquests, he lacked the Frenchman’s easy manner on screen and never convinced as a romantic playboy.

“One thing you know in films,” said Gilbert, “is that you always end up with what you begin with. If you begin with a piece of s*** that’s what you’ll end with, doesn’t matter how you change things or what you try. The story couldn’t be told in under three-and-a-quarter hours…it had been deliberately structured for a certain type of audience” which didn’t really exist back then.

Paramount virtually committed publicity suicide by holding the press show on a Boeing 747. Even a Jumbo Jet could not present the movie on anything except a tiny screen which made nonsense of the movie’s 70mm credentials. While projected on one screen, it was only shown in 16mm, people at the back could hardly see it and the sound was terrible. Gilbert considered it “the worst experience of my life.” Worse, few people had ever flown a 747 before so to quell nerves, the journalists were tanked up, which didn’t help their mood when they came to write scathing reviews.

After the press screening, it was heavily cut. And with roadshow on the way out, it received few 70mm bookings in the U.S. though that format was more welcomed in Europe. (In my local city of Glasgow, in Scotland, it ran for 10 weeks in roadshow presentation at the ABC Coliseum, a decent stint).

Oddly enough, it was relatively well-received by audiences. It pretty much made its money back which was a big achievement given the budget and certainly did not fall into the category of being a loser.

SOURCES: Lewis Gilbert, All My Flashbacks,(Reynolds and Hearn, 2010) p279-288, p295-304; “Interview with Lewis Gilbert,” British Entertainment History Project, August 13, 1996, Reel 13; Brian Hannan, Glasgow at the Pictures, 1960-1969, (Baroliant, due later this year).