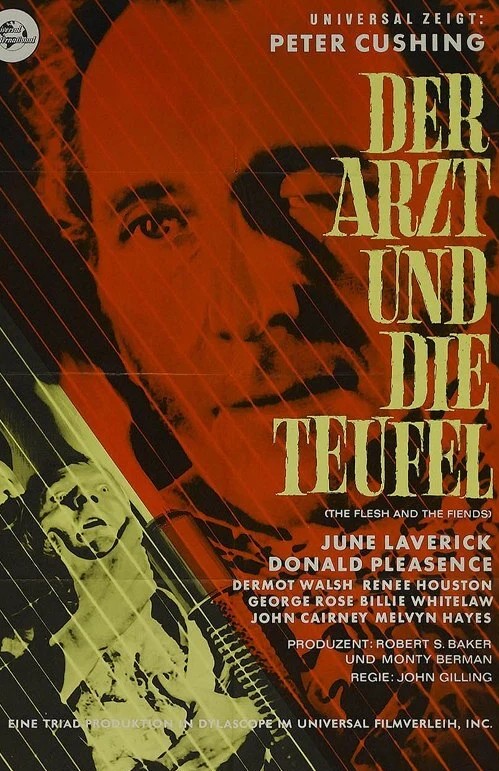

Hypocrisy runs rampant as an entitled medical hierarchy effectively condones vile practice. Of course it wouldn’t do to have Peter Cushing, who generally hounded demonic fiends like Dracula, to be tabbed a villain so with a little bit of jiggery-pokery he gets off scot-free and, in fact, is considered so much above other mortals that he receives a standing ovation at the end.

The self-justification, or deification if you like, of Edinburgh surgeon Dr Knox (Peter Cushing) is promoted on the back of primitive medicine, whereby, through sheer ignorance and laziness surgeons were more apt to kill than to cure.

Dr Knox is an advocate of using recently interred corpses to teach his students the real fundamentals of anatomy. However, his colleagues feel that the use of fresh corpses goes against the grain and there was no such thing in the early 19th century of donating your body to medical science. Grave-robbing was a crime.

Enterprising duo Burke (George Rose) and Hare (Donald Pleasance) get round that problem by skipping the burial aspect, murdering assorted drunks and vagabonds and delivering fresh meat to the good doctor, who turns a blind eye to their actions, determined as he is to improve teaching standards. He’s not the only one who believes that a streetwalker, killed in this fashion, has achieved more in death than life.

The good doctor has a conscience in the shape of Dr Mitchell (Dermot Walsh) who is wooing his daughter Martha (June Laverick), but he eventually comes round Knox’s way of thinking. The hierarchy in the shape of the Medical Council would get their claws into Knox were it not for the fact that in their incompetence they inflict more damage than good.

As a sub-plot, and as a way of weaselling into the lower classes who provide the bulk of Burke and Hare’s supply chain, earnest medical student Chris Jackson (John Cairney) falls for drunken goodtime girl Mary (Billie Whitelaw) who spends as much time making fun of him as she does sharing his bed.

You would have thought the high mortality rate of the period would not have made the local populace suspicious of a few extra deaths, but when Burke and Hare kill too close to home – Mary, Jackson and Daft Jamie – townspeople like a regular Transylvanian village mob light their torches and head off in pursuit.

The question of whether Knox was in collusion with Burke and Hare becomes the crux. But given the medical profession does not want to bring itself into disrepute, he is given a free pass and declared not guilty.

The high-mindedness which Peter Cushing (The Skull, 1965) usually brings to a role works in his favor here and, until the death rate mushrooms, audiences may be inclined to go along with his thesis that fresher corpses should be made available as a matter of course to doctors. His pinpoint arrogance brooks no quarter. He’s in entitlement heaven. And that his superiors back off informs you that hierarchies were as good at closing ranks and defending themselves then as now.

This was the first venture of Donald Pleasance (Soldier Blue, 1970) into the sleazy characterizations which would become a trademark. The nervous tics were a later addition. Here’s he’s mostly sweaty.

I should profess an interest. John Cairney was a relative of our family but acknowledging his work in our household was limited to such less contentious material as Jason and the Argonauts (1963). Along with Billie Whitelaw (The Comedy Man, 1964), he was in the rising star category. Both deliver solid performances. You might also spot Melvyn Hayes of the It Ain’t Half Hot, Mum series (1974-1981).

Dodgy accents abound, Pleasance and Rose affect Irish accents and Whitelaw makes a stab at a Scottish one. I was surprised, given the date, to see a deal of nudity, but it transpires I was watching the “continental version.”

Directed by John Gilling (The Reptile, 1966) from a screenplay by himself and Leon Griffiths (The Hellfire Club, 1961).

You catch this on YouTube