Template for The Godfather (1972) and Succession. King Henry II (Peter O’Toole) has to choose an heir from Richard (Anthony Hopkins), Geoffrey (John Castle) and John (Nigel Terry). Helping set the Machiavellian tone are Henry’s wife Eleanor (Katharine Hepburn), his mistress Alais (Jane Merrow) and French King Philip II (Timothy Dalton). Cue plotting, confrontation, double-crossing, rage and lust.

Some other complications: the queen is actually a prisoner, the result of organising a failed coup against her husband, the sons participating in this attempt to overthrow their father, and with Henry willing to sacrifice his mistress in order to achieve an alliance with Philip, relations are less than cordial all round. Eldest son Richard, strong and aggressive, would be the obvious choice, and should be the only choice I would guess by law, but Henry prefers the youngest son John, who is weak, while the middle son Geoffrey is the most savvy (see if you can guess how easily these characters fit The Godfather scenario, or Succession for that matter). Geoffrey reckons that even if passed over for the top job, he will rule from behind the scenes as John’s chancellor.

This is not your normal historical picture with battles, romance and, let’s be honest, costumes, taking central stage. And there’s little in the way of rousing speeches. Virtually all the dialog is plotting. And, like Succession, there are elements of vitriol and pure comedy. In five crisp opening scenes we know everything we need to know. The King brings his family together for Xmas, the Queen freed for the occasion, to decide the succession. Richard is shown in hand-to-hand combat, the wily John leading a cavalry attack, the whiny John pouting and complaining, Alais realizing just how much a pawn she is in the game as Henry explains she is to be married off to Richard.

And if you are not the chosen one, your only chance of gaining the throne is by the back door, by having a powerful ally in your pocket, one whose armies would threaten the King, which is where Philip comes into the equation as potential kingmaker. Let the intrigue begin, especially as those who ought to be little more than bystanders – the women – have ideas of their own. “I’m the only pawn,” says Alais, “that makes me dangerous.” Despite her current status, Eleanor still owns the French province of Aquitaine and taunts her husband by revealing that she slept with his father.

The plot twists and turns as new alliances are formed between the conspiring individuals. The overbearing Henry will certainly remind you of Logan Roy, “When I bellow, bellow back.” And there is a Hitchcockian element in that we, the audience, know far more than the participants and wait for them to fall into traps. Richard is revealed as homosexual, having had an affair with Philip.

The dialogue is superb, brittle, witty, and it could have been all bombast and rage except that emotion carries the day. Henry clearly could not have wished for a better Queen than Eleanor, more than capable of standing up to him, more capable than any of his sons, and he probably wishes she was by his side rather than confined, as by law, to prison. Eleanor still retains romantic notions towards him, even as she forces him to kiss his mistress in front of her – only the audience sees the truth revealed in her eyes, not Henry who is too busy kissing. The uber-male Richard complains to Philip that he never told him he loved him.

Maternal and paternal bonds ebb and flow and throughout it all is the dereliction caused by power. A father will lose the love of the children he rejects. Or, realizing they are more powerful together than as individuals, they could turn against him. The mother faces the same fate – she risks losing the love of the ones she does not back.

Unlike Alfred the Great, the monarchs have stately castles, so the backdrops are more commanding, but once an early battle is out of the way, it is down to the nitty-gritty of plot and counter-plot. A truly satisfying intelligent historical drama.

Peter O’Toole (Lawrence of Arabia, 1962) had played Henry II before in Becket (1964) and is in terrific form. Katharine Hepburn (Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, 1967) won her second successive Oscar – and her third overall – in a tremendous performance that revealed the inner troubles of a powerful woman, Anthony Hopkins (When Eight Bells Toll, 1971) gave an insight into his talent with his first major role.

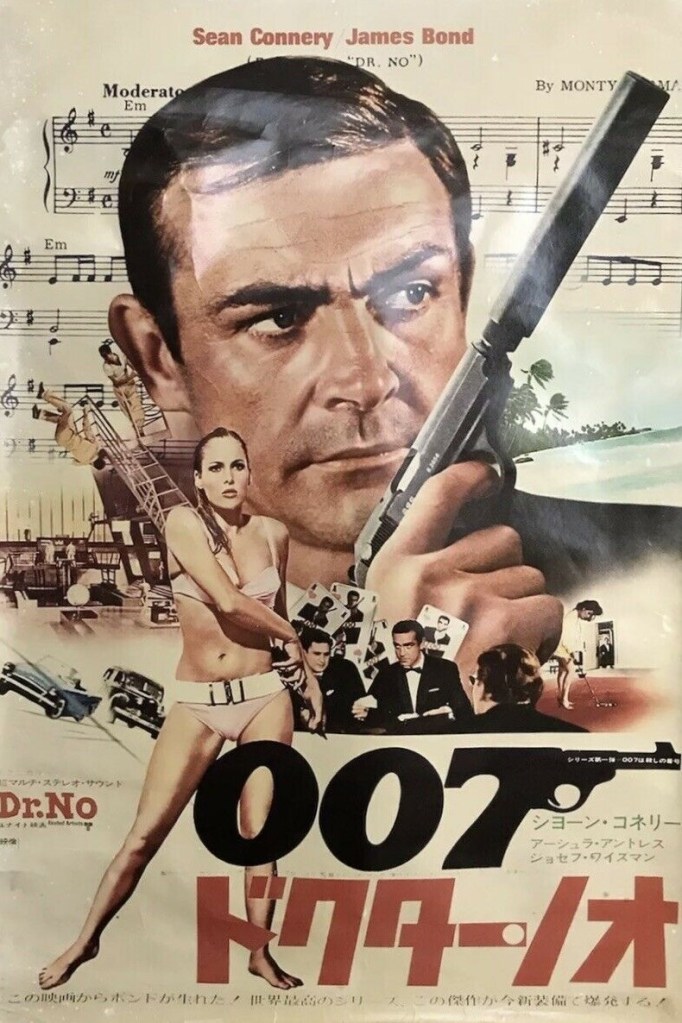

John Castle (Blow Up, 1966), Nigel Terry (Excalibur, 1981), Jane Merrow (Assignment K, 1968) and future James Bond Timothy Dalton, in his movie debut, provide sterling support, Dalton and Castle especially good as a sneaky, conniving pair.

shorter than most of the genre. But the 600-seat Odeon Haymarket in London’s West End

was an ideal venue for building word-of-mouth and it ran for over a year.

Modern audiences might bristle at the idea of woman as commodity, but women in those days were the makeweights in alliances of powerful men, though the fact that they bristle at the notion as well evens up proceedings, Eleanor in particular happy to jeopardize Henry’s ambitions in favor of her own, Alais warning Henry to beware of the woman scorned.

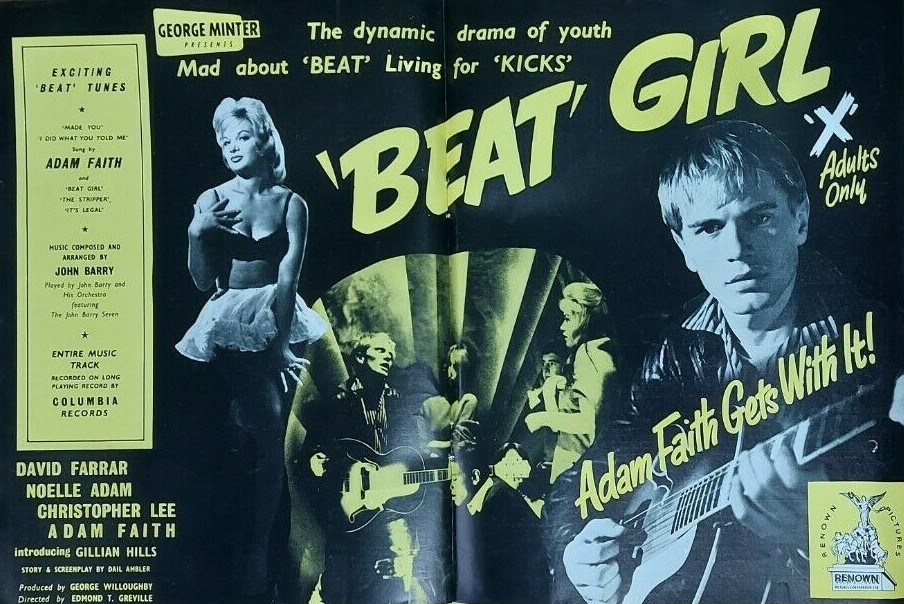

Director Anthony Harvey (Dutchman, 1966 ) was deservedly Oscar-nominated. James Goldman (Robin and Marian, 1976) won the Oscar for his screenplay based on his Broadway play which had not been in fact a runaway Broadway hit, only lasting 92 performances, less than three months. John Barry (Zulu, 1963) was the other Oscar-winner for his superb score.