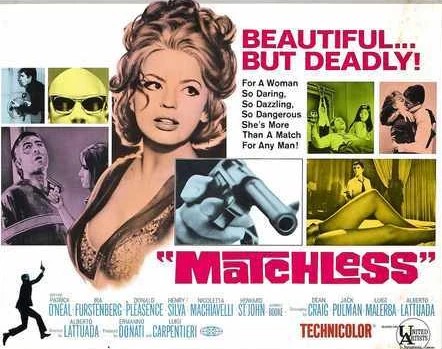

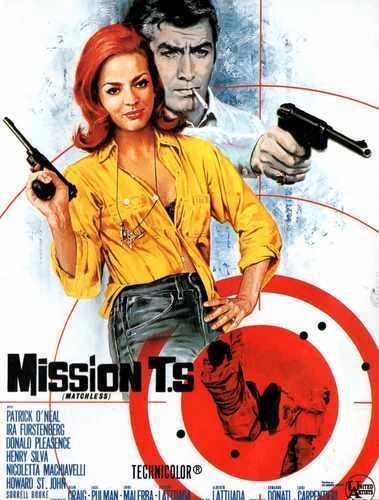

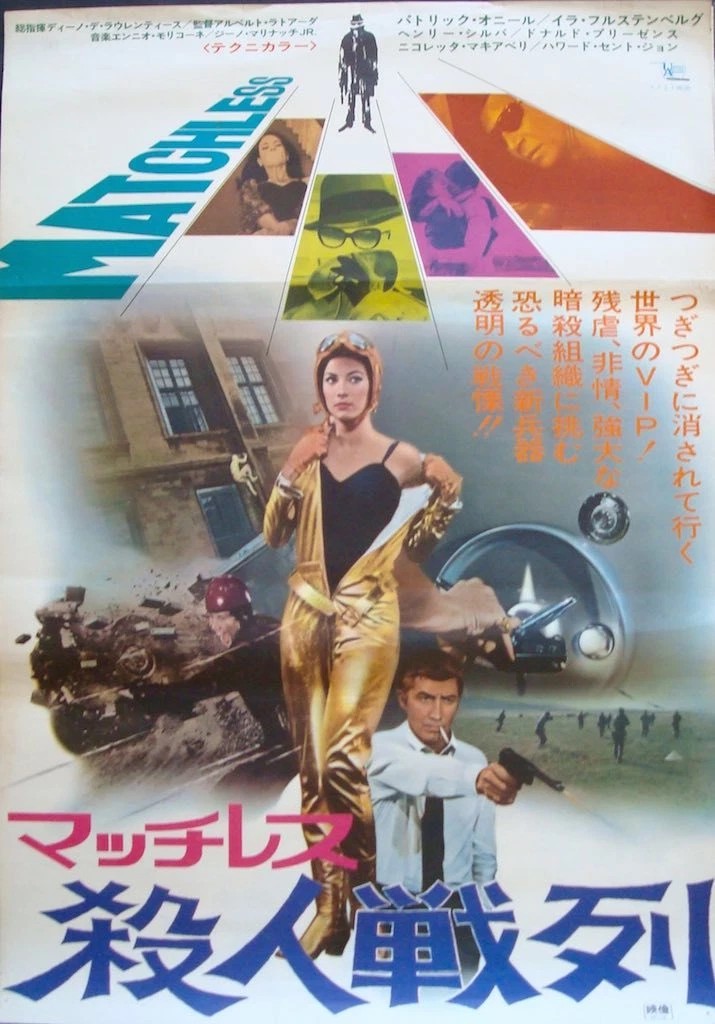

Alberto Lattuada is the big attraction for me here, being the director of World War One spy drama Fraulein Doktor (1968) starring Suzy Kendall and which has become a standout, in terms of views, on the Blog. Conversely, you might be swayed by the undoubted physical attributes of Ira von Furstenberg (The Vatican Affair), a real-life princess to boot, or perhaps by the under-rated Patrick O’Neal (Stiletto, 1969) enjoying a rare foray as the top-billed star.

While the U.S. title is a tad opaque – our journalist hero Perry Liston (Patrick O’Neal) uses that by-line – the foreign title gives the game away. While imprisoned in China, Perry is handed a ring with magical powers by a Chinese prisoner in gratitude for helping him out. The ring permits a brief snatch of invisibility every ten hours, resulting in the screenwriters having to ration its appearance. As with any such charm, it provides opportunity for tension, humor and sexual frisson.

Another inmate Hank (Henry Silva) wants the ring for himself so spends a lot of the movie chasing, catching and losing Perry. The U.S. Government reckons a touch of invisibilkity will come in handy when dealing with arch-villain Georges Andreanu (Donald Pleasance) who has the usual arch-villain’s penchant for world domination. If it’s not enough that people are hunting him for the magic ring, Perry has others on his trail once he steals Andreanu’s secret serum. (Sensibly, the screenwriters shy away from what actually the serum does in the way of helping the arch-villain along in his quest for world domination – all that detail never did much to enhance the Bond/Flint/Helm stories.)

And like any decent spy of the era, Perry has women throwing themselves at him, some just for the hell of it but others who use sex to their advantage. O’Lan (Elisabeth Wu) falls into the first category, Tipsy (Nicolatta Machiavelli), a henchwoman of Andreanu, into the second, while artist Arabella (Ira von Furstenburg) has him guessing, Instead of a girl in every port, Perry has a girl in every country, China, Britain and Germany.

Perry isn’t a superhuman spy in the James Bond mold, and he’s not forced to keep it going with spoofery of the Derek Flint/Matt Helm variety, and he’s often at a disadvantage, caught naked, for example, when the invisibility spell wears off, and allowing Arabella to generally outwit him.

The central conceit works well in the context of the movie, helping and hindering Perry in equal measure. But there are also plenty other original touches: a car chase where the vehicles end up on top of a train, Hank watching a Man from Auntie series on television, tension racked up when villains come inadvertently close to the ring, hypnotism to fix boxing matches, torture by spinning, facial transformation, an amphibious car, a set-piece in a bank.

There’s more serious intent than you might expect, a satirical view of good guys and bad guys. Americans and Chinese apply the same kind of torture to Perry and employ the same plastic surgery method to send spies in undercover. While Perry is at his most powerful – i.e when invisible – he is also at his weakest by being naked.

Patrick O’Neal and Donald Pleasance (who appeared as Blofeld the same year in You Only Live Twice) have a ball though Ira von Furstenberg steals every scene she’s in. Henry Silva has the opportunity to try out his comedy acting chops.

Not in the same vein as Fraulein Doktor but generally consistently holding the interest.