The bursting of the B-movie bubble dealt a death blow to the careers of the two stars here. In the past, rising talent who failed to make the marquee grade could find almost a lifetime of contentment in low-budget westerns, neo-noir thrillers and down’n’dirty exploitationers with the hope of an occasional supporting role in a bigger picture to ease their path. By the end of the decade, just about the only option were Roger Corman biker flicks or spaghetti westerns. Especially if they had gone down the tough guy route, B-pictures might have provided an exemplary move for both Alex Cord and Patrick O’Neal. As it was, this was their last shot at the big time. And it was lean pickings.

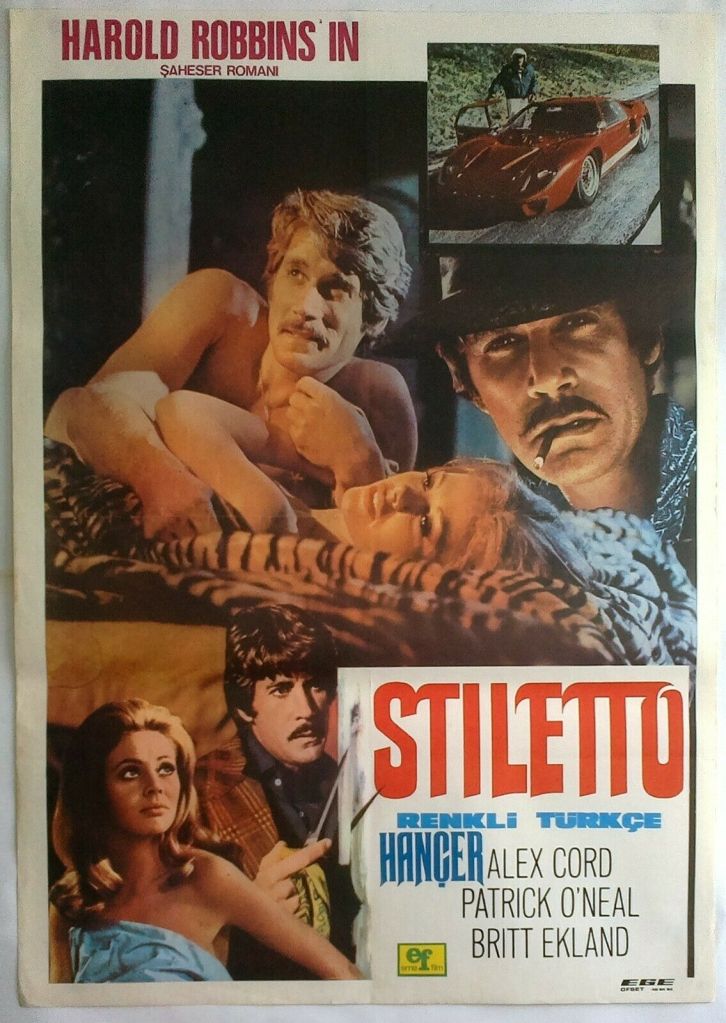

Retirement can be a tough call any time for a high-flying businessman. But when you’re at the top of your profession in the Mafia, loosening such ties can prove problematic. Count Cesare (Alex Cord) is a part-time assassin, spending the rest of his time as a fun-loving playboy with a string of women, fast cars and racehorses. Only problem is, he wants to retire from the Family – and not in normal fashion, weighted down by a block of cement. Unfortunately, his dilemma doesn’t solicit sympathy from boss Matteo (Joseph Wiseman).

Adding to his problems is tough cop Baker (Patrick O’Neal) on his tail who fastens onto illegal immigrant Illeana (Britt Ekland), Cesare’s girlfriend when he’s not pursuing Ann (Barbara McNair). A strictly by-the-numbers thriller it’s enlivened by two underrated tough screen hombres. Alex Cord (The Brotherhood, 1968) isn’t given enough of a character here to tug at audience heartstrings although elsewhere he had proved better-than-expected value. If anything, he’s an existential kind of hero.

Cord made a brief splash as an action hero in the monosyllabic Clint Eastwood/Charles Bronson mold after debuting in the John Wayne role of the Ringo Kid in the remake of Stagecoach (1966) and didn’t have more than half a dozen stabs at making his name on the big screen before disappearing into the television hinterlands. So he’s something of an acquired taste, maybe the small output enough to qualify him for cult status. Here, he’s a decent fit for the violence but saddled with a role that makes little sense.

Patrick O’Neal (El Condor, 1970) followed a similar career trajectory, swapping television with the occasional movie and even managing a screen persona as a snarky type of villain/supporting character. A few more tough-guy roles and he might well have built a stronger footing in the business.

This is another thankless role for Britt Ekland (Machine Gun McCain, 1969), there to add glamor, but, surprisingly, she manages to bring pathos to the part. Barbara McNair (If He Hollers Let Him Go, 1968), always worth watching and who had made an auspicious debut the year before, hardly gets any screen time.

Director Bernard L. Kowalski (Krakatoa, East of Java, 1968) proves better at the action than the characterization, though, luckily nobody needs to be anything other than tough. Three scenes, in particular, are well handled – the opening murder in a casino, a shoot-out a penthouse and the climax on a deserted island which has more than a hint of a spaghetti western. Joseph Wiseman (Dr No, 1962) rustles up another interesting performance and collectors of trivia might note Roy Scheider (Jaws, 1975) putting in an appearance.

This old-style tough-guy thriller would have been better off had the Cord vs. O’Neal set-up taken center stage, with the assassin on murderous overkill hunted down by the zealous cop. As it is, it’s a missed opportunity for Cord to develop an Eastwood/Bronson persona and enter the action star hall of fame.

Based on a thin Harold Robbins bestseller, the screenplay by W.R. Burnett (The Great Escape, 1963) and A.J. Russell (A Lovely Way to Die, 1968) doesn’t take any prisoners.

Doesn’t quite deliver what it says on the tin, but interesting to see Cord and O’Neal battle it out.