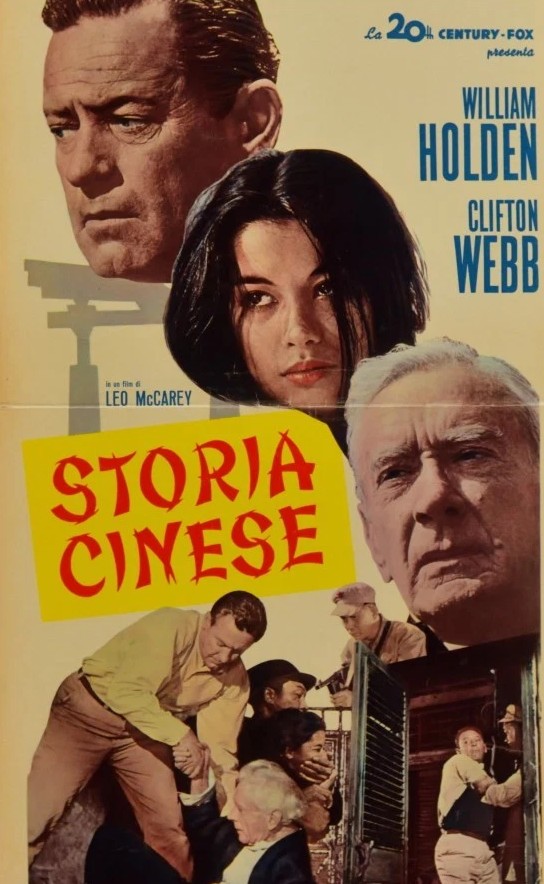

Of all the misguided sentimental anti-Communist drivel, this is a very poor swansong for triple Oscar-winning director Leo McCarey (Going My Way, 1944). A tone that’s awkward enough all the way through goes straight through the wringer when we are asked to accept without question the actions of a rapist. Such genocidal rape as the conqueror visits on the conquered would sit less comfortably with a contemporary audience.

Most of the problem is the set-up. Apart from those pesky Communists invading a Christian Mission, in other circumstances this would have settled into a verbal sparring match between about-to-retire old priest Fr Bovard (Clifton Webb minus trademark moustache), full of tetchy quips, and his younger replacement Fr O’Banion (William Holden) trying to shake off the unwelcome advances of even younger native Siu Lan (France Nuyen). There would be a servant or maybe a more high-flown doctor whom O’Banion could push Siu Lan onto.

There’s laffs aplenty if you’re easily satisfied with the likes of a servant (Burt Kwouk in an early role) who believes thieving is compatible with Christianity, O’Banion’s woeful attempts at cooking and his inability to shoo away the ardent Siu Lan, and the priests risking breaking a golden rule of their religion to enjoy a glass of wine before the clock strikes midnight.

The arrival of the Communists is not initially too tiresome, Bovard doing his best headmaster impression keeps them in line, Communist leader Chung Ren (Robert Lee), an ex-Christian, sweet on Siu Lan. Things get tricky when Chung Ren’s attempts to forcefully claim the woman are deterred by O’Banion who is tested several times on the old Christian principle of turning the other cheek before resorting to unchristian violence.

Chung Ren then rapes Siu Lan anyway. But when she stabs him in the back and the rapist is forced to ask O’Banion to go to another mission to fetch the necessary penicillin to prevent infection spreading, the older priest is inclined to ignore the request and let him die. O’Banion thinks he has struck a deal to free the old priest in exchange for fetching the medicine, but Chung Ren reneges on the agreement and the priests are tortured and stand trial.

Meanwhile, Chung Ren has a change of heart, or so it seems, after Siu Lan gives birth to his son. But, actually, this might be more to do with the fact that he has been demoted for not being a good Communist, inclined to enjoy the finer things in life rather than share them out with his comrades. And it’s only when he’s told he’s going to be sent away to some kind of Chinese Gulag that his principles make an appearance and he helps the two priests and Siu Lan and her baby to escape.

I could see maybe Siu Lan being forced into marriage by Chung Ren in the Communist state while he was in a position of importance; she would have no choice in the matter. But for her to show the same acceptance in a democracy outside China smacks of the worst kind of wishful thinking. Sure, the Christian God is all-forgiving and, technically, all Chung Ren would have to do was confess the sin of rape and equally technically he would receive absolution and therefore in the Church’s eyes be free to marry.

But O’Banion overheard the rape. He’s a witness. That’s no use in the Communist society, but in a democracy you would have thought he would have been seeking prosecution. As he was a witness and this was not something protected by the sanctuary of the confession, he would not just be perfectly within his rights but would have to seek out rule of law.

I have never heard of a rapist and the woman he raped living happily ever after and I doubt if it would ever have been considered conceivable even in the early 1960s.

That aside, William Holden (The Devil’s Brigade, 1968) and Clifford Webb, in his last picture, are good value as the squabbling priests, less so when they venture into dubious morality. France Nuyen (A Girl Named Tamiko, 1962) doesn’t get a fair shake, required to be the cliché happy grinning native and then provided with no opportunity to state her case against her rapist before she’s pushed, for the sake of a fairy tale ending, into marriage.

Written by the director and Claude Binyon (North to Alaska, 1960) from the bestseller by Pearl S. Buck.