Only thing better than seeing this on the big screen is seeing it on biggest screen possible, Some clever clog has blown it up to 70mm by scanning the “original 6-perf 35mm Vistavision camera negative in 13k with all restoration work completed in 6.5k. The 70mm film print was created by filming out a new 65mm negative.” I don’t know what it means either – except that extra 5mm is the soundtrack and perfs refers to height – but I’m delighted with the result.

Not only does the crop spraying scene bask in greater glory but the pivotal scrambling on Mount Rushmore where Hitchcock used the wide screen at its widest takes on a vivid clarity that’s just impossible watching a DVD when characters are literally hanging off the furthest edges of the screen.

But setting aside the widest widescreen-ness what seeing it on the big screen more than anything restores is the audience experience and that allows the sly humor to reach its full potential. I hadn’t realized just how funny this darned picture is, not just the eye-rolling mother treating her grown-up son as a michievous scamp, and the zingers of lines but the interplay between the various characters.

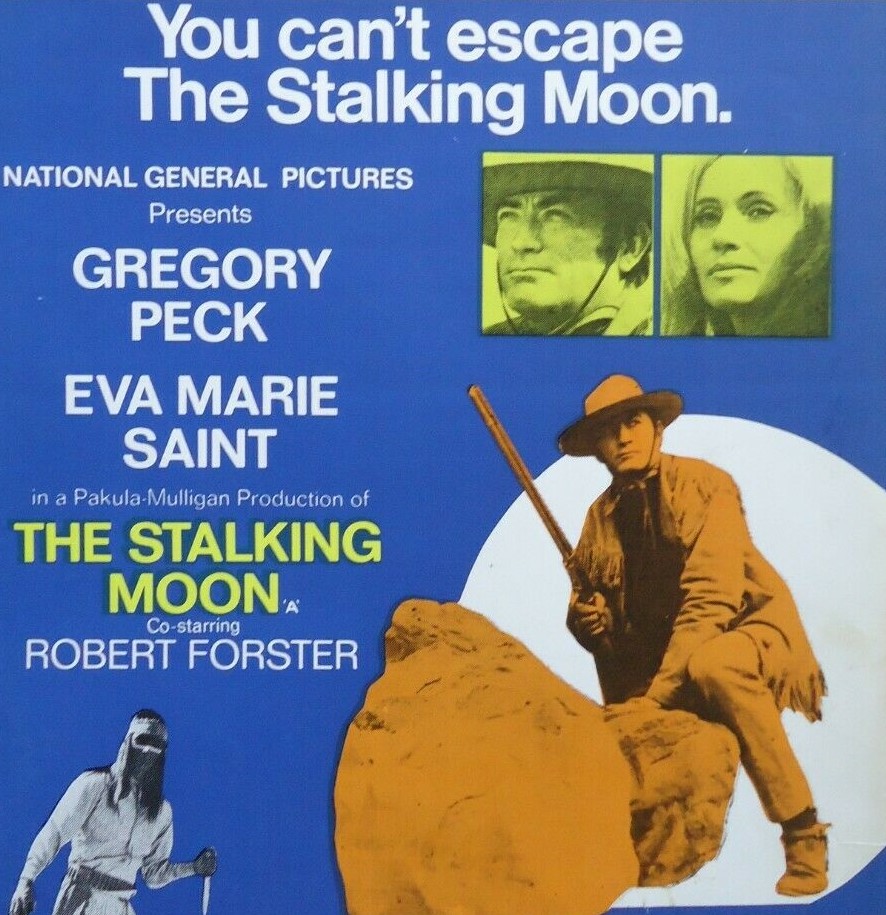

And putting to one side Hitchcock’s wizardry it is a tour de force for screenwriter Ernest Lehman. I must have counted at least 20 narrative beats, not just thriller or action twists and turns but changes in our appreciation of the characters, plus the devilishly clever sexual banter. And while hero Roger Thornhill (Cary Grant) is a hero by accident, heroine Eve Kendall (Eva Marie Saint) is heroine by design, and thanks to her exceptionally callous boss, The Professor (Leo G. Carroll), likely to pay a heavy price for wanting to do something worthwhile in a life that from her looks seems as if aerated, gliding along with nary a care in the world, her beauty ensuring she would always garner easy attention.

There are some exceptionally clever moments that emanate from Lehman rather than Hitch. The elusive villain hiding behind a variety of identities is finally unmasked as Vandamm (James Mason) at an auction when the auctioneer calls out his name as he buys an artefact that contains stolen microfilm. And so a scene that appeared there for a different purpose – the emotional one of Van Dam realizing he has been cuckolded and Kendall realizing she is going to lose the only man she ever truly loved – turns out to play a vital role in the narrative, critical to the ending.

Given Hitch suffered from accusations of misogyny it’s astonishing how often he serves up exceptionally self-confident women who can string men along, in this case two men, Eve using Roger for mere sexual gratification while seducing Van Dam for the more serious business of snaring a traitor and giving her life meaning. And can there have been a more convincing femme fatale? That is, not the obvious kind as in film noir where a male dupe is easy pickings for a clever female and her seduction techniques over-obvious.

Here, the seduction is not only very gentle, and to some extent baffling, and achieving through language and screen dexterity a marvellous intimacy, but her femme fatale-ness only revealed when she secretly sends a note to Van Dam asking what does she do with her victim in the morning.

There are lot of elements more obviously coming to your attention on the big screen. The irony of a cab firm being called “Kind Taxis” especially in New York where their drivers err on the side of the irate. The train porter whose clothes we think Roger has stolen only for a quick cutaway to reveal him counting his bribe. The cleverness of that disguise. How many red-capped porters will you find in a train station?

A lot of the time Cary Grant (Walk, Don’t Walk, 1966) doesn’t have a great deal to do except react sometimes to very little at all. When he’s waiting to be collected at the crop field he makes his feelings known through shifting his gaze and jiggling with his trouser pockets.

There’s even a scene that might have given Sergio Leone the idea for his famous shootout in Once Upon a Time in the West (1969) where, on first meeting, Roger and Van Dam circle each other with the camera taking each’s POV.

This is just overloaded with delights – the drunken Roger telling the cops to call the cops, using his only phone call in jail to call mother, escaping from thugs in an elevator by the “women first” device, the amazing innocence when he encounters locked doors, clearly expecting them still to be left open to facilitate his escape.

Hitchcock – and to a greater degree in The Birds (1963) – ushered in the random action explosion (gas tankers always seem to be convenient) that would become de rigeur in the genre and used with less finesse here when the crop plane crashes into the tanker and car passengers stop to gawk allowing our hero the chance to steal one and escape.

It generally passes unnoticed how Hitch sets up his main character. At the start of films, especially these day when viewers are in on the gimmick, most audience eyes are on spotting the directing putting in his trademark appearance, rather than assessing Roger as a workaholic advertising executive, dragging his secretary out of the office when she should be on her way home so he can dictate a few more lines to her in a taxi, and inadvertently setting himself up as the kind of man who tells lies for living who for once must stick to the truth.

Grant’s acting ability was rarely fully recognized. Here the more urgent question seems to be how many suits he got through in filming (16) rather than the way he holds the picture together. And only Hitch would keep the audience waiting 30 minutes before introducing the female lead and make it hard for the maternally-dominated Thornhill to exude any sexual attraction after being under the thumb of mother for the first section.

This was the British premiere of the 70mm version so look out for it turning up at your local arthouse. Perhaps someone will go the whole hog and accord Hitch the contemporary honor of re-tuning his pictures in Imax.

I am assuming that I saw the 70mm version of the new 4k that’s just being released.

Not to be missed on big screen or small.