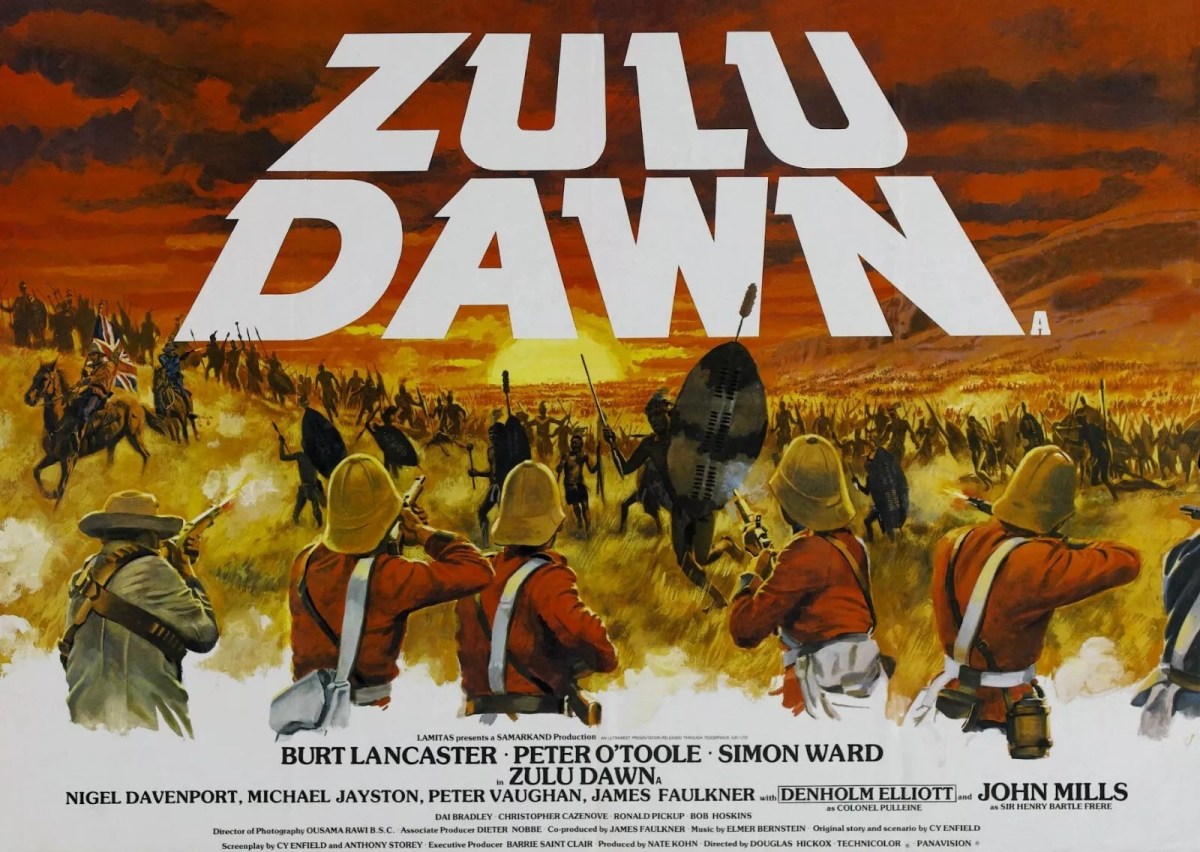

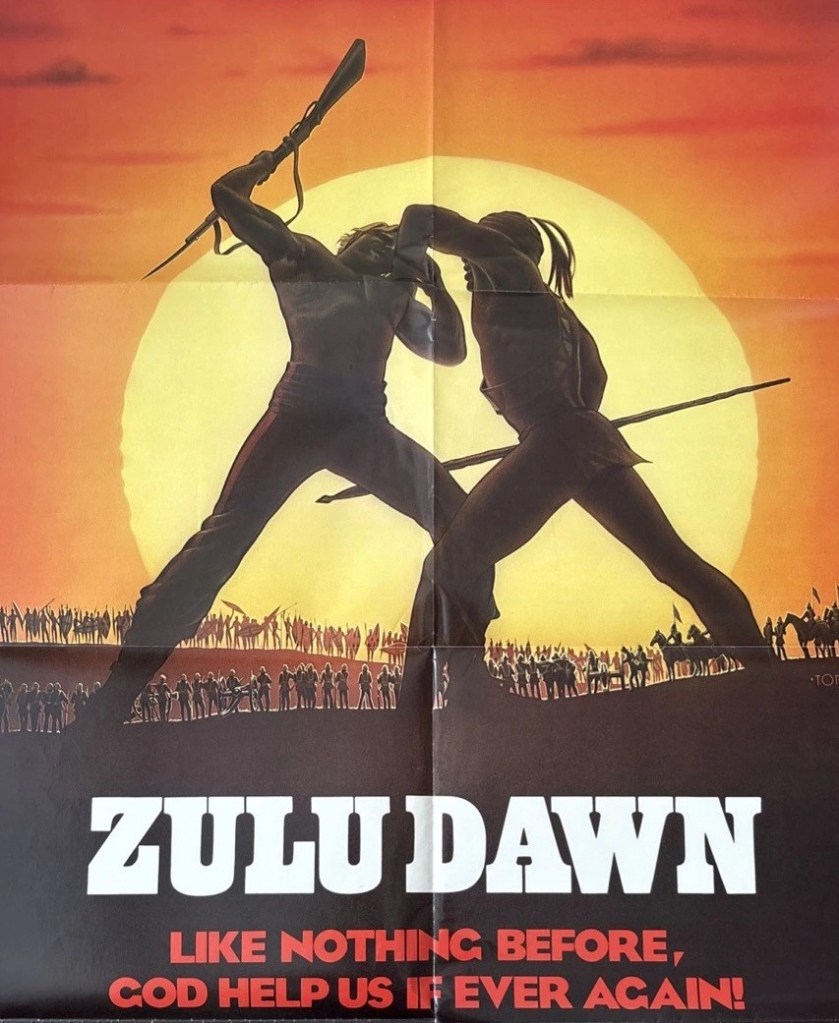

You’d wonder why anyone would want to make a film about this calamitous military disaster, the Battle of Isandlwana in 1879. Yet, such subjects have always attracted Hollywood, especially if some kind of triumph can be snatched from defeat – Dunkirk (1958 and 2017) – or some charismatic figure of the order of General Custer is involved – They Died With Their Boots On (1941), Custer of the West (1967). Or you can make something mythical such as The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936) and with the assistance of the screen presence of Errol Flynn tilt it towards glory or you can take the same subject (the 1968 version) and make merry with satire should you wish to poke fun at the British Empire.

The latter could easily have been the starting point for Zulu Dawn, a prequel to the majestic Zulu (1964). However, although the Brits were outthought, out-maneuvered and outnumbered, the errors made on the battlefield were generally not through hubris or commanders competing for glory. And you would have to assume that no matter what the British Army could do, in terms of size it was minute compared to the Zulus, and even armed with rifles and artillery was hardly going to withstand a sustained attack.

So it’s fairly solid stuff, buoyed up by decent performances, though Burt Lancaster playing an Irishman seems tacked on to increase marquee appeal. The final shot of the eyes of Peter O’Toole would easily stand in the annals of war pictures as one of the best testaments to the horror of defeat and impending humiliation.

There is certainly some unsavory business at the start as British commander Lord Chelmsford (Peter O’Toole) and diplomat Sir Henry Bartle Frere (John Mills) unwittingly poke the lion of Zulu King Cetawayo whose rising strength they perceive as a threat to the British colonies in the southern regions of Africa. Chelmsford makes the mistake of invading Zululand.

Hoping to pin down the enemy to the traditional pitched battle on territory that would give him an advantage, he finds he’s chasing ghosts. They can’t locate the Zulus until the enemy wants to be found. And in an echo of the later Lawrence of Arabia, Cetawayo does the impossible and leads his troops on what was considered an unlikely line of attack.

The British strategy of lining up troops in two lines and shooting alternately certainly reduces the oncoming force, but four times the amount of firepower would still have had trouble preventing the onslaught. Critically, in search of more favorable ground, Chelmsford splits his forces, but, again, even had the British been one unit, it would have made little difference.

I’m not sure how true is the portrayal of the officious quartermaster Bloomfield (Peter Vaughn) who, even in the heat of battle, demands soldiers form an orderly queue to receive a supply of bullets, and that may just be a potshot at overbearing bureaucracy.

The narrative flits from various characters, dashing cavalry types like Col Durnford (Burt Lancaster) and Lt Vereker (Simon Ward), commanders Chelmsford and Col Pulleine (Denholm Elliott), those representing different points of view such as Col Hamilton-Brown (Nigel Davenport) and Col Crealock (Michael Jayston), and lowly grunts in the form of Colour Sergeant Williams (Bob Hoskins) and Boy Pullen (Phil Daniels).

There’s certainly a sense of the higher-ups still enjoying the pleasures of life, wine served at dinner, plated service, but the lesser ranks still have largely an easy time of it, when they are not marching spending most of the time in idleness. It’s a very civil environment. Commands aren’t barked out. “I say, would you mind…” is the tone.

But it’s the marching that’s the killer. The heat’s not as bad as in Crimea and there’s no disease decimating the ranks but they still have to do a lot of walking on uneven terrain. There’s enough difference of opinion at all levels of the Army to keep tensions high.

And there’s more of a focus on the brutality of war – Lt Vereker laments the death of a Zulu child, you can easily be killed by your own troops and truth is viciously beaten out captives (who, as it happens, have been sent to become captives and mislead the Brits.) I was wondering if audiences had come to expect a scene with native girls dancing half-naked, as had occurred in the sequel, and the censor turned a blind eye to.

Peter O’Toole (The Lion in Winter, 1968) has the best role, especially when he counts the cost of defeat. Burt Lancaster (Valdez Is Coming, 1971) offers some star power but little else and the rest of the cast is virtually a roll-call of Who’s Who in British acting.

Luckily, the picture is more than even-handed and while not pillorying the Army and the Establishment in the manner of The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968) plays fair with the circumstances and exalts Zulu victory as much as British defeat.

Directed by Douglas Hickox (Les Bicyclettes de Belsize, 1968) with perhaps overmuch concentration on marching. Zulu director Cy Endfield had shot his bolt by this point and wasn’t invited back except in the capacity of screenwriter along with Anthony Storey making his movie debut.

Much better than I expected.

If you fancy checking out how it compares to Zulu (1964), you can check out my review on the Blog.