Stunning opening section thrown away by shifting tone and despite excellent performances by the Oscar-nominated Alan Bates and Dirk Bogarde drifts into Kafkaesque virtue-signalling.

But let’s get the title out of the way first. I had assumed a “fixer” was a manipulator, an underworld type of character who could, for a price or future favor, sort out problems or find someone a job or act as an intermediary between politicians or businessmen. Not so. Yakov (Alan Bates) is nothing more than a handyman, who can fix broken windows or railings and turn his hand to anything such as wall-papering or basic accountancy.

In the credit sequence he demonstrates his skills by fashioning with wood, a couple of screws and some steel, a razor, with which to remove the hair and beard that would identify him as a Hassidic Jew. He is, as soon becomes apparent, afflicted by dogs. As he departs his remote cottage in a cart, a vicious dog so disturbs his horse that it bolts, resulting in the loss of a wheel. He continues his travels on horseback, arriving in a small town in time to witness a parade and Cossacks rampaging through the streets.

As it’s set in Czarist Russia, his journey is accompanied by melancholy violin with, for some reason, a disturbing undercurrent of military drum. As the credits end, we cut to the Russian flag and a marching band. He hides in terror as the horsemen drag people along by the ear, slash with sabers, hang others. It’s a pogrom, the type of attack commonly experienced by Jews living in ghettoes.

Up to now, it’s just outstanding. Then it tips into the picaresque. Yakov helps an old drunk Lebedev (Hugh Griffiths) who’s fallen down in the snow in the street. As reward he is offered work wall-papering a room. He has a prick of conscience when he realises that Lebedev is an anti-Semite. Lebedev’s daughter Zinaida (Elizabeth Hartman) seduces him. But, on spotting some blood on a cloth, he refuses to go through with the act.

Luckily, my reading of crime novelist Faye Kellerman has alerted me to the fact that it is an act of faith for Jews not to make love when a woman is menstruating. Luckly, Zinaida isn’t so up on her Bible (Leiticus 15: 19-23 in case you were interested) that she catches on to this revealing fact, for, as has been pointed out earlier, minus the distinctive curl, Yakov doesn’t have the physical characteristics associated in those times with a Jew. In fact, you would say Lebedev would more easily pass for one.

Anyway, Lebedev gives him another job, of counting the loads leaving his brickworks because he suspects he is being swindled. But the foreman, who has been rumbled, and suspects Yakov of being a Jew, calls in the Secret Police, it being a crime for Jews to leave the ghetto.

Now we tip into Kafka. The initial charge against Yakov is that he harbored another Jew during Passover. But then things spiral out of control. He is accused of passing himself off as a Gentile (non-jew), attempted rape of Zinaida and then of ritual murder, killing a small child.

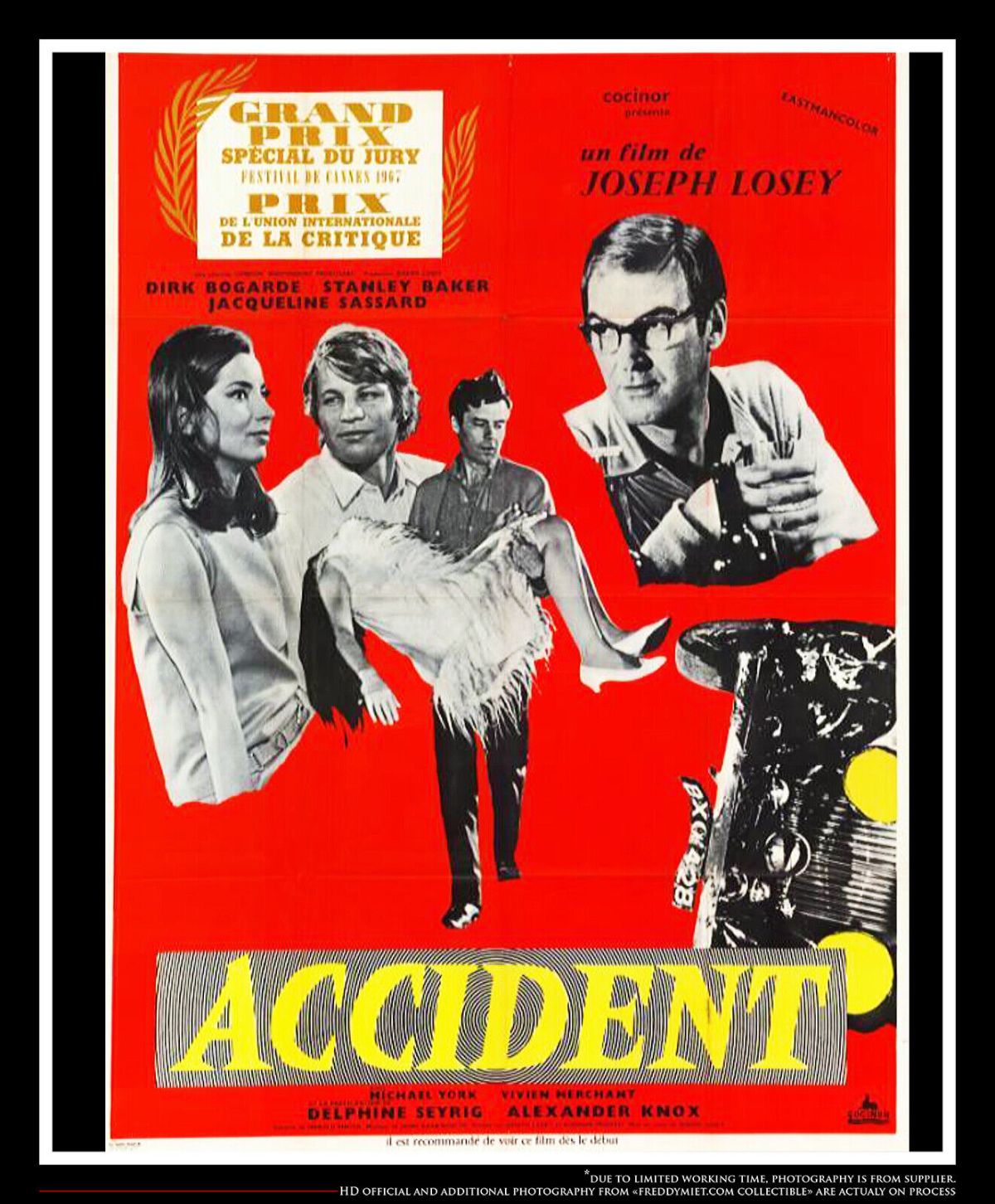

Investigating magistrate Bibikov (Dirk Bogarde) is sympathetic and manages to avoid the rape charge much to the fury of prosecutor Grubeshov (Ian Holm) but once the other charges mount, he is nailed, everyone determined to prove an innocent man guilty.

This is based on a true case and clearly was a case of persecution and Yakov’s transition from worker happy to hide his ethnicity to gain work to a man who rediscovers his religion is a piece of great acting from Alan Bates. But the points are hammered home endlessly and where director John Frankenheimer (The Train, 1964) so deftly dispensed with dialogue in the superb opening sequence, now he more than makes up for it with leaden speeches, and a film that would worked better for being considerably shorter.

It feels like Hollywood is hard at work. After some moments of mild happiness Yakov’s cinematic chore is to invoke sympathy for an entire nation rather than taking on the Holocaust directly. Dalton Trumbo’s (Lonely Are the Brave, 1962) screenplay is filled with brooding lines. But providing Yakov with an interior monologue when he dithers over having sex doesn’t work at all, certainly not next to the more effective use of that technique in John and Mary (1969).

At the outset, Frankenheimer treats violence with discretion. We don’t see the dog being impaled on a saber, just its corpse thrown at Yakov. We witness a rope being wound round a man’s neck, as innocent of any crime as Yakov, but not the actual hanging. So what begins as highly-nuanced turned into a battering ram of a picture and characters forced into lines like “the law will protect you unless you are guilty” and “I am man who although not much is still more than nothing.”

Alan Bates (The Running Man, 1963) certainly deserves his Oscar nomination and Dirk Bogarde (Modesty Blaise, 1966) might feel aggrieved he missed out on a Supporting Actor nomination. But too many of the rest of the cast over-act. It’s an all-star cast only if you’re British. But check it out if you’re a fan of Hugh Griffith (The Counterfeit Traitor, 1962), Elizabeth Hartman (The Group, 1966), David Warner (Perfect Friday, 1970), Ian Holm (in his sophomore movie outing), Carol White (Daddy’s Gone A-Hunting, 1969) and Georgia Brown (Lock Up Your Daughters!, 1969).

Frankenheimer at his best when he lets the action play without the overload and there’s one almost Biblical scene, lit only by candlelight, that demonstrates his cinematic virtuosity. But otherwise it’s drowned in the verbal rather than the visual. Trumbo based his screenplay on the Pulitzer Prize winner and bestseller by Bernard Malamud.

Some effective moments, but too long drawn-out to make the impact expected.