Lot feistier than the heart-warming genre might suggest with the usually restrained Henry Fonda (Advise and Consent, 1961) coming over like he’s had a gagging order lifted, letting rip not just with a plague of cuss words but damning to Hell every hypocrite under the sun. A perfect example of the haves and have-nots where to become elevated to the former you need to know your Latin.

Despite loathing religion, quarry miner Clay (Henry Fonda) has got quite the Biblical spirit, no intention of girding his loins when he can sire nine kids, a heck of a crew to support from meager wages. He enjoys the kind of pleasures – add alcohol and gambling to his lust – that his God-fearing neighbors find objectionable, though they put those aside when he’s neighbourly enough to carry out repairs on their property for no charge.

When wife Olivia wants him to break open the piggy bank to fund a graduation ring for their oldest, Clayboy – what was wrong with just calling your kid Junior, I wonder – (James MacArthur), her dream clashes with his. He’s already spent the money on the power saw he needs to cut down to size the logs with which he is building his dream house, a bigger building, and brand-new, so his offspring don’t need to sleep five or six to a room or on the floor.

Clayboy is astonished to discover he’s the top dog at school but winning the class medal opens doors poverty prevents him getting through. Even when the local pastor Clyde (Wally Goodman) finds a last-minute loophole, Clay’s excellent grades don’t meet qualification criteria for college, he’s lacking in Latin.

But if there’s one thing Clay has learned to overcome, it’s adversity and soon a scheme is hatched. But even that has a drawback. A scholarship won’t cover all the costs. While Olivia accepts the principle that God intended them to be poor, Clay rejects that notion, the kind that keeps the downtrodden in their place, denying them the opportunity for betterment that comes with education.

This ain’t no sermon but it’s not The Grapes of Wrath either. Poverty hasn’t kicked the living daylights out of everyone but nobody seems able to catch a break even when one is floating tantalisingly close. Ain’t a family saga either, covering too short a period of time, and little but a series of loosely-connected episodes that eventually come together.

Clay gets the preacher in the mire for filling him full of booze, telling him it’s a cure for mosquito bites, while the pair are fishing. Public revulsion at the drunk pastor loses the preacher his congregation. Clay sorts it out by berating the churchgoers as hypocrites and threatening to withdraw his free labor when it comes to repairs. Come the Latin crisis, turns out the preacher was an ace scholar in the subject and can do the teaching, on the condition that the anti-religious Clay attends church.

In the meantime, there’s another kind of education required of Clayboy. Claris (Mimsy Farmer), whose training extends to reproduction and pores over the unexpurgated dictionary, gleefully hovering over the dirty words, has to teach the young man that a young woman wants more than whispers in the ear and bunches of flowers. Unfortunately, Clayboy has another suitor Cora (Kathy Bennett) who doesn’t take kindly to him rejecting her advances and when the opportunity arises to sabotage his plans does so with pleasure.

This is a film about working people. Not labor as such, and not about labor unrest or agitation either. In the way of Witness (1985), there’s a great scene (minus the soaring music of course) of constructing a wooden building, there’s men drilling and hammering at the quarry, and a pivotal scene in chopping down a tree. People seeing the benefit of hard work are less convinced by the ephemeral attraction of education, especially when that seems either beyond their reach, out of their league or as likely to find as the end of a rainbow.

So without overly saying anything much about the class divide in the U.S. (which is unspoken anyway and assumed, what with equality and all, not to exist) this says a great deal.

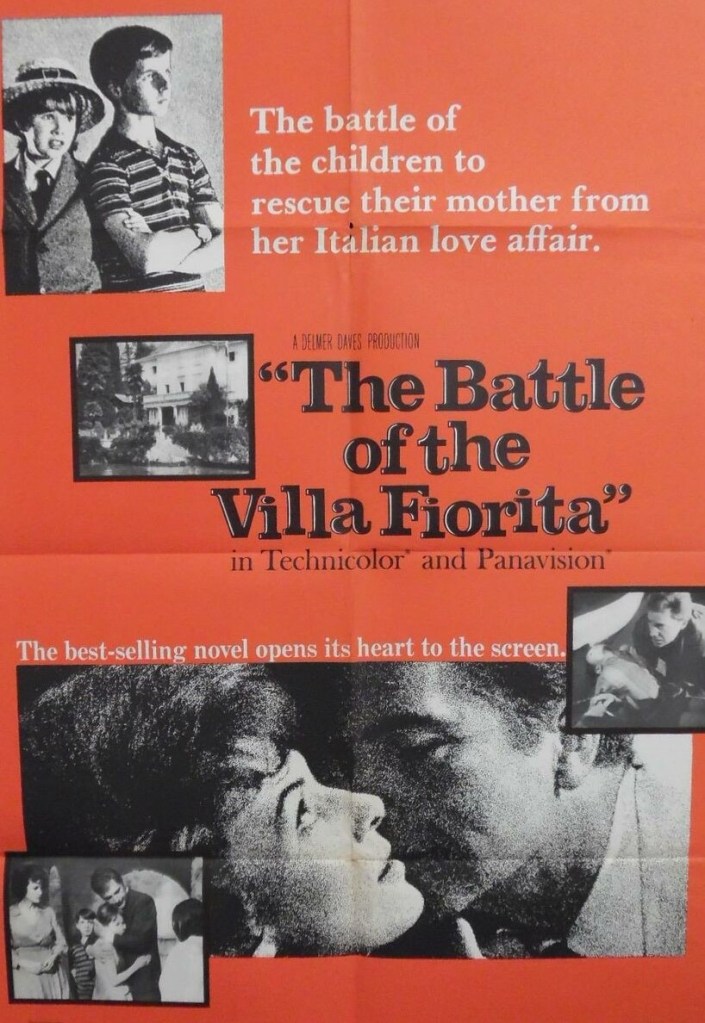

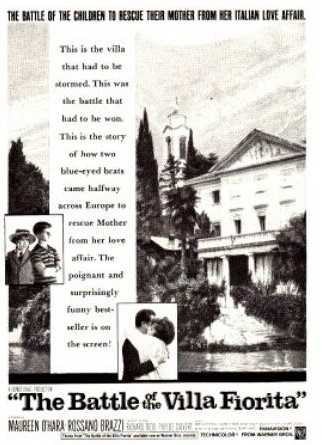

Henry Fonda fills his boots. It’s a plum role and he goes for it. Certainly, it’s the opposite of all those buttoned-up parts he seemed to land. Maureen O’Hara (The Battle of the Villa Florita, 1965) has a smaller part and it’s a mercy after nine kids she managed to keep her figure. James MacArthur (Battle of the Bulge, 1965) has every scene stolen from him by the charming minx Mimsy Farmer (Bus Riley’s Back in Town, 1965). You might spot Donald Crisp (Pollyanna, 1960) in his final role.

If you equate director Delmer Daves with hard-hitting westerns like Broken Arrow (1950) and 3:10 to Yuma (1957), it’s worth remembering he had a strong romantic streak as exhibited in Rome Adventure/Lovers Must Learn (1962). But he deliberately avoids the comedy pratfall of the later Yours, Mine, Ours (1968), also starring Fonda. He wrote the screenplay based on the book by Earl Hamner Jr.

Because this reputedly led to The Waltons TV series, you could be mistaken for thinking it’s as schmaltzy. It’s anything but. Take away the lush background and the idyllic scenery and while it finally gets to a heart-warming climax it’s tougher going and with a sexuality way ahead of its time.

Great watch.