Gambling dominates the 12-page A3-sized Pressbook with the legend of the sinister yet charming Arnold taking pride of place in the editorial section rather than, as would be usual, the actors. So we are given the inside story of the famous betting coup with Sidereal at a New York race track, but fleshing out the man shown on screen, exhibitors also learned that Rothstein was known as the “banker of the underworld,” how he won $600,000 in a poker game and a masterpiece painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds.

Not touched upon in the picture, but included here, was that he owned an art gallery, chartered ocean liners to transport liquor from Europe, ran protection rackets in the garment industry, and was instrumental in creating what became known as “The Syndicate.” In short, the Pressbook set out to built Rothstein up as even more fabulous figure than shown in the film.

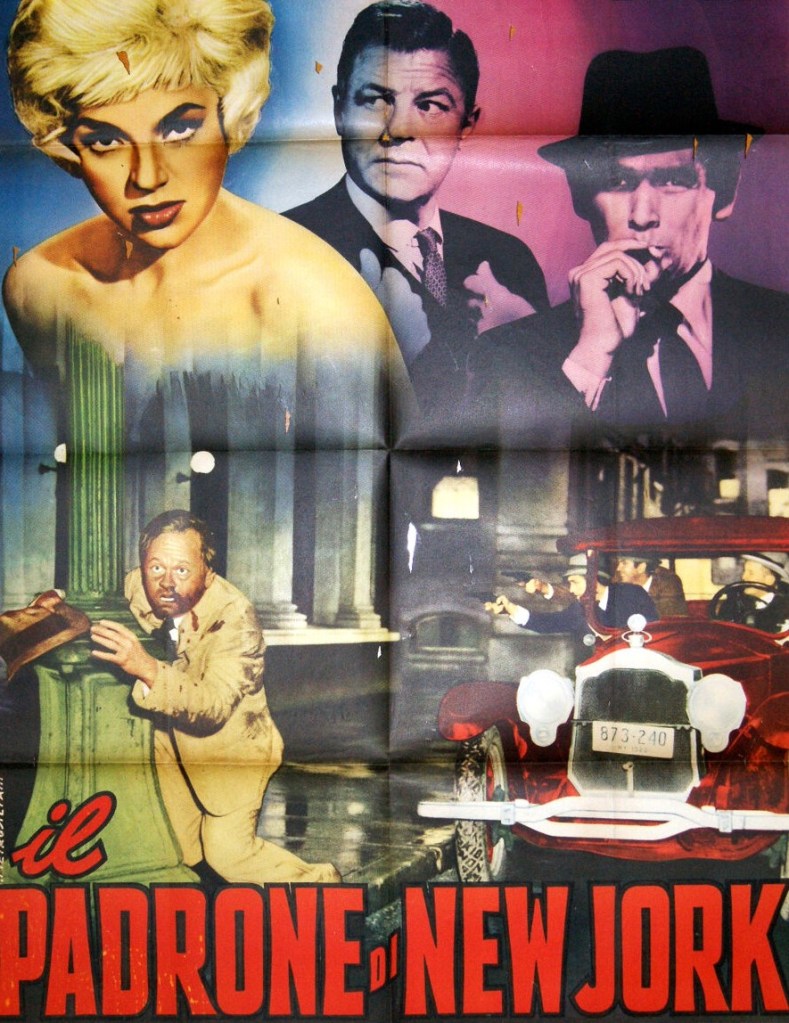

As with Jessica, and as pointed out in my report on that Pressbook, the producers took the unusual step of sticking with the one dominant image in the poster of David Janssen (as Rothstein) leaning over a poker table with fistfuls of cash in his hand and Dianne Foster (Rothstein’s wife) at his back– although it’s possible in this instance the single-image approach was to reduce costs since this was in fact a glorified B-picture. The rest of the poster is an amalgamation of various scenes – racehorses, showgirls, people dancing the Charleston, a drive-by shooting. In the absence of one big star billed above the title, a total of 10 actors have their names below or their faces running down the side, almost giving the impression that it is an all-star ensemble picture.

After paying his dues in television with four years as Richard Diamond, Detective (1957-1960), David Janssen was a relative newcomer to a leading role although his performance in a second-billed role in war film Hell to Eternity (1960) had caused him to be touted as the new Clark Gable / Cary Grant. He was lucky that he had already been signed up for King of the Roaring 20s for his next picture after Here to Eternity was critical stinker and box office bomb Dondi (1961).

Other journalistic nuggets included that an Arab sheik once offered 100 camels for British star Diana Dors, Mickey Shaughnessey revealed as a Golden Gloves boxer, Dianne Foster previously taught modelling, and Keenan Wynn had a plate in his jaw. David Janssen’s sister Teri made her debut and their mother Berniece was an extra while Timmy Rooney, son of Mickey, was drafted in to play Johnny Burke as a youngster.

Not surprisingly several promotional ideas aimed at exhibitors revolved around gambling. One suggestion was to place a gambling wheel in the lobby with anyone landing on the numbers 7 or 11 winning a pair of guest tickets. Exhibitors were urged to get in touch with the local vice squad to see if they would donate confiscated gambling equipment for lobby display. Giving away cards that provided information on betting odds was another notion.

To get audiences into the mood of the era, cinema managers could run Charleston contests or a tie-in with a fashion store marketing clothes from the period or attire models as “flappers” to parade around town, especially in an open-top car from the era. More straightforward was a new movie tie-in paperback edition of The Big Bankroll, the book that inspired the picture, published by Cardinal.