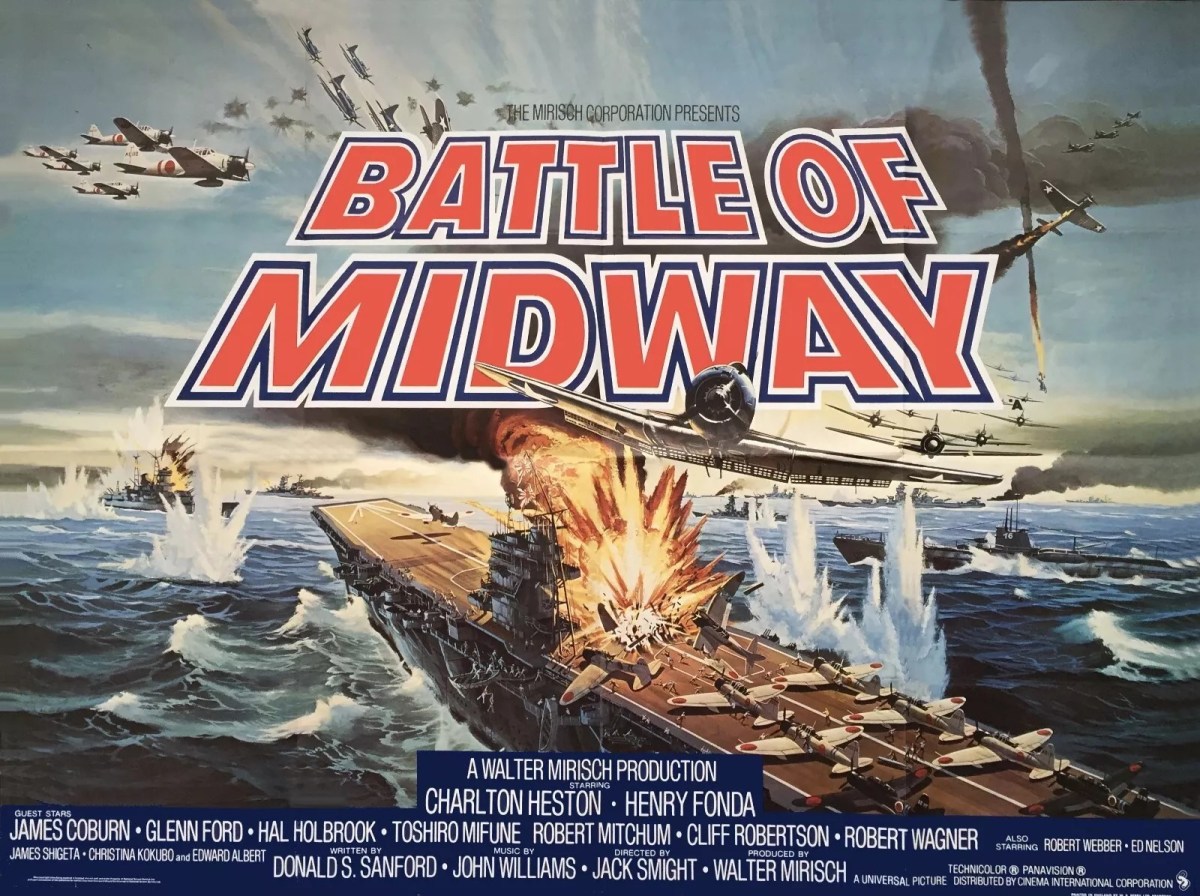

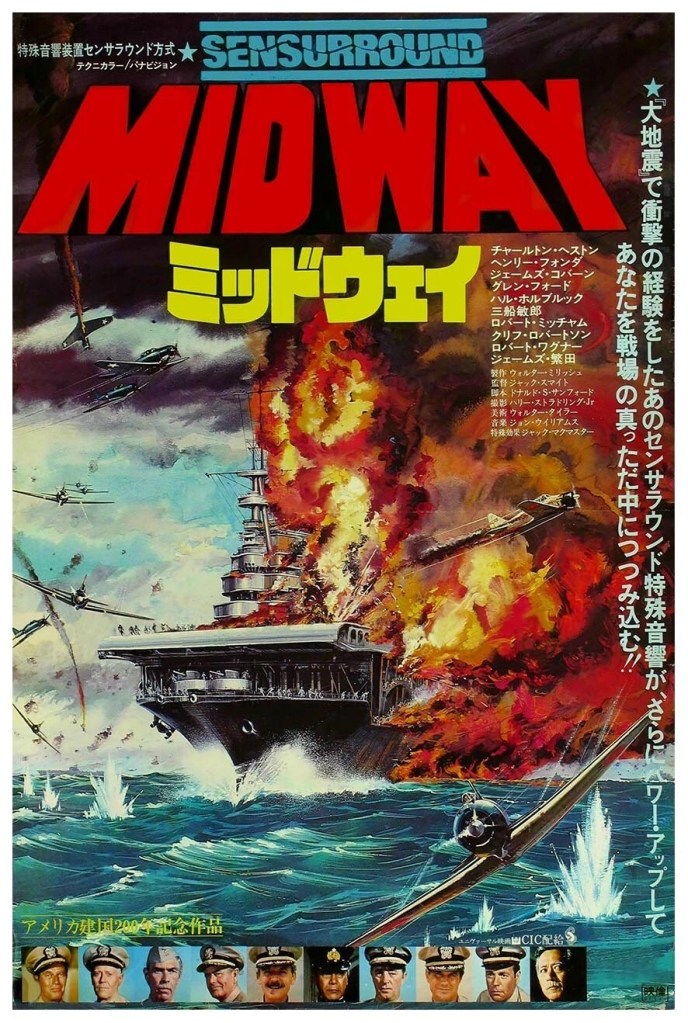

Even-handed documentary-style tale recounting of the most famous U.S. naval battle of all time, a turning point in the struggle for control of the Pacific in 1942. Both sides make mistakes, luck and judgement play an equal part.

I’d always assumed Midway was some abstract geographical position without any idea of its strategic importance – did the name mean it was halfway between the U.S. (or Hawaii) and Japan? But here I learned it was an actual island that the Japs planned to invade and the Americans intended to stop them. In some senses, it was bait, a way to draw the U.S. Navy out of Pearl Harbor. But the bait ran both ways. If the Yanks could coax the enemy out into the Pacific, they had a chance of gaining an advantage, even though the Americans were inferior in shipping tonnage.

The Japs have been stung into action by the audacious American bombing of Tokyo. Admiral Yamamoto (Toshiro Mifune) uses the perceived threat of further attacks to gain official approval for his plan to invade Midway.

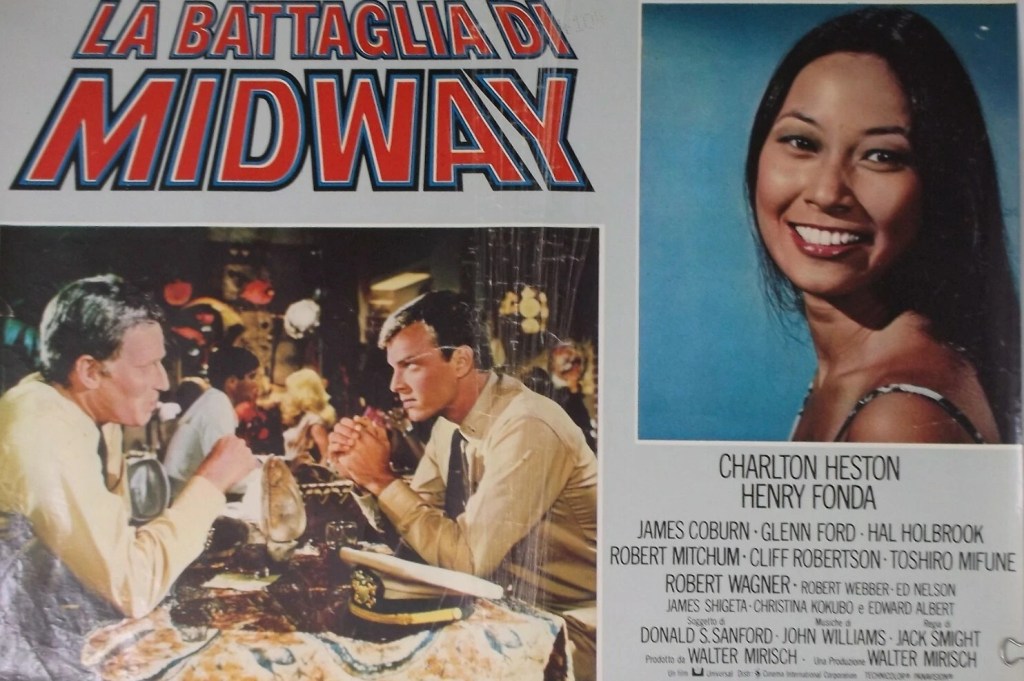

This is strictly a male show. However, in a bid to lower the testosterone levels a romantic subplot is inserted. The aviator son, Lt Thomas Garth (Eddie Albert), of top aide and former pilot Captain Matthew Garth (Charlton Heston) has an American-born lover Haruko (Christina Kobuko) of Japanese descent who’s being investigated for espionage and subsequently interned. On intervening, the father digs up a hodgepodge of racism – from both sides, Haruko’s parents against her forming a relationship with a non-Japanese. But the plan backfires causing a breakdown between father and son.

But that’s very much on the fringes and although it raises interesting cultural aspects, the movie concentrates mostly on the nuts-and-bolts of heading into a major engagement.

American intelligence, headed by Commander Joe Rochefort (Hal Holbrook), gets wind of the planned attack. But the clues are scant – the old trope of increased radio traffic not enough to convince – and while the audience knows the Japs are on the move with a mighty naval force including four top-class airplane carriers, the Americans remain ignorant almost until it’s too late.

Luckily, Admiral Nimitz (Henry Fonda), heading up the American naval contingent, is keen to inflict a blow on the enemy, even though he’s limited to two carriers and another just out of the repair yard. Each side relies on spotter planes to detect the enemy. But the Japanese, by imposing radio silence, shoot themselves in the foot, unable to switch tactics until too late. The hunch plays an important part.

There’s rarely much opportunity for individual heroics on a ship under fire, beyond rescuing someone. The fighter pilots are a better bet, especially since some of their forays are nearly suicidal given the firepower they attract. Matt Garth, who for most of the picture is an upscale backroom boy, is called into action with unexpected results.

Most battle films tend to concentrate on the heroics often at the expense of understanding in any detail what’s going on. Thankfully, this is different. We are kept informed of every change in the conflict. And whereas you might think that dull, in fact I wouldargue that it adds substantially to the tension, and the fact that the only one of the commanders who looks as if he could throw a punch (Robert Mitchum) in the manner of John Wayne is confined to his bed thus forcing the movie to concentrate as much on brain as brawn.

Audiences at the time welcomed all the talking and this was a substantial hit. Snippets of old war footage were carefully sewn into the lining of the action, bringing the kind of authenticity that moviemakers reckoned moviegoers craved. For me, there was more than enough going on already.

Nimitz’s decision to go for broke rather than dive for cover results in victory but he’s no gung-ho commander, rather presented as a thoughtful but determined individual. The lack of backstage effort especially in the communications department was partly to blame for the humiliation of Pearl Harbor but here these guys share the glory.

Boasting the kind of all-star cast that used to be the hallmark of the 1960s roadshow, this has a bunch of top-notch actors, albeit most just flit in and out of the picture. Charlton Heston (Planet of the Apes, 1968) effortlessly shoulders the main burden with Henry Fonda (Once Upon a Time in the West, 1969) the fulcrum of all decision-making. Robert Mitchum (The Way West, 1967) , James Coburn (Our Man Flint, 1966), Glenn Ford (Rage, 1966), Cliff Robertson (The Devil’s Brigade, 1968) and Toshiro Mifune (Red Sun, 1971) all feature.

Jack Smight (Harper / The Moving Target, 1966) directs from a script by Donald S Sanford (Mosquito Squadron, 1969).

Thoroughly engrossing.

- I’m doing a Behind the Scenes tomorrow.