Action-packed superior James Bond rip-off belonging to the Eurospy subgenre and elevated by memorable lines, wit and visual imagination. So if you recall any movie where ricochets play havoc in a room, this is where it originated. Flying through a window on a rope and then crashing through a series of rooms and not stopping, ditto. That famous line uttered by Johnny Depp in Pirates of the Carribean (2003) about “the marchandise,” yep, you’ve guessed it. Although it did steal a nice touch from Robin and the 7 Hoods (1964), the one where an illegal drinking den (illegal casino here) is remarkably transformed.

And all the promise star Horst Buchholz showed in The Magnificent Seven (1960) and kept stowed away all these years, that’s back in spades. Chases, fistfights, shootouts, saloon (well, casino, actually) brawl, competing ruffians, safe-cracking, hitmen, infiltration of secret hideout, a pair of femme fatales and the inevitable atomic scientist.

Some clever thugs including Schenk (Klaus Kinski) dupe the U.S. government out of a million bucks by only pretending to hand over a missing scientist, instead pocketing the cash and blowing up a plane with him on board. With for the time suprising use of forensics, the CIA determines the man killed in the plane wasn’t the missing scientist and work out that he might well be getting sold on to China.

Camera footage taken of the plane crash scene points to mysterious underworld figure Tony (Horst Buccholz). Against her superior’s wishes, agent Kelly (Sylva Koscina) heads off to the titular city in pursuit, tracks down Tony with no great difficulty to his illegal gambling den just in time to witness the electronic miracle of the roulette wheels disappearing into the floor when the cops turn up. The electronic scam would have worked except for a drunken customer who demands his chips be cashed and the only way to silence him being for Tony to slug him and trigger a brawl.

Under the cover of which, Kelly sneaks into Tony’s office whereupon finding no evidence of either a million bucks or a missing scientist, she asks for a job. “Strip!” he demands. But that’s not for licentious reasons it transpires, but to examine the labels on her clothing, from which he and his henchmen deduce (I won’t bore you with the details but they do match up) she’s a plant.

However, she is the one, accidentally, to trip over the Chinese conspiracy, in, of all places, a cemetery. Eventually, she persuades Tony to help her out, although that’s for financial rather than patriotic reasons. She’s got a few tricks of her own up her sleeve, and under the guise of kissing him, steals his keys.

Kelly kind of fades in and out of the picture – which is a shame because she’s good value in a feisty seductive clever way – while all the chasing of opposing sets of criminals is down to Tony. First target being the man with the steel hand (though not the steel claw that in the old British comic The Valiant allowed him to become invisible).

The non-Chinese criminals are as likely to kill their own men to stop them coughing up. But mostly, Tony and his gang are stalking the two sets of criminals, Kelly mostly waiting in a car or popping up to ask questions, with Tony being driven off a mountainside, thrown off a tower, duelling underwater and avoiding a scalding in a sauna. But we’re talking the Houdini of spies and none better than when escape involves commandeering a bulldozer and ramping up over a bunch of vehicles (that idea’s got to have appeared in a later film, too).

Kelly’s the good kind of femme fatale, the spy who has to use her wiles to snare the bad (or badd-ish) guy. But she’s a rookie compared to Elizabeth (Perette Pradier) who leads Tony a merry dance by first of all pretending to be a victim.

But there’s style by the bucket load, clever reversals by the ton. There’s a marvellous scene where Tony knocks out a guy and then with nowhere to hide him props him up at a piano only to be undone when the fella slides over and hits the piano keys. Ever seen someone use the rolling coin distracting device. Or when the rope between two stanchions snaps mid-air casually sliding down the broken end. Or sex indicated by one person hanging their bathrobe over a door after the other person has done the same. Or the hero doing up a bikini top instead of undoing it. And a leading man who spends more time in a state of undress than any of the females. And, for good measure, a couple of times, and this very much in the contemproary idiom, breaking the fourth wall.

Once we get going it’s the kind of non-stop action we later equated with Taken (2008) or John Wick (2014). Horst Buchholz was never better, a brilliant light touch with the lines and good deal tougher with the fists. Sylva Koscina (A Lovely Way To Die, 1968) has less to do than you’d like once the rival femme fatale appears but she shows just how capable an actress she is in displaying in non-verbal fashion and in a three-shot of all things her jealousy.

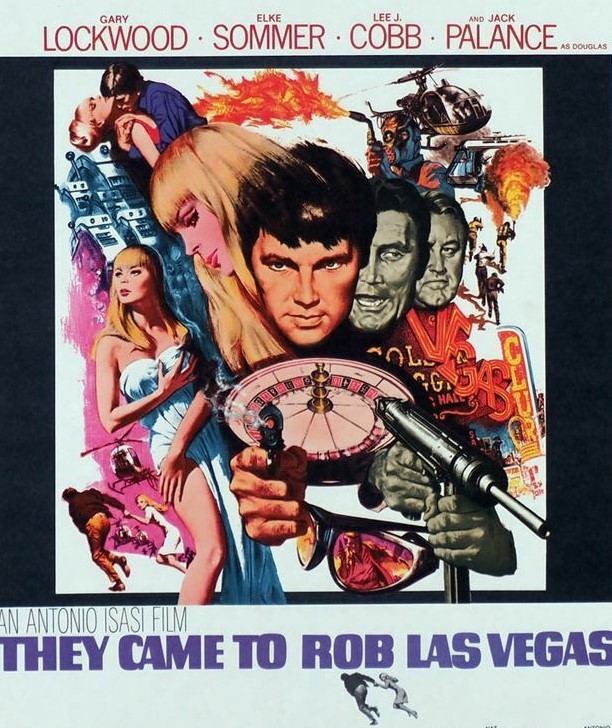

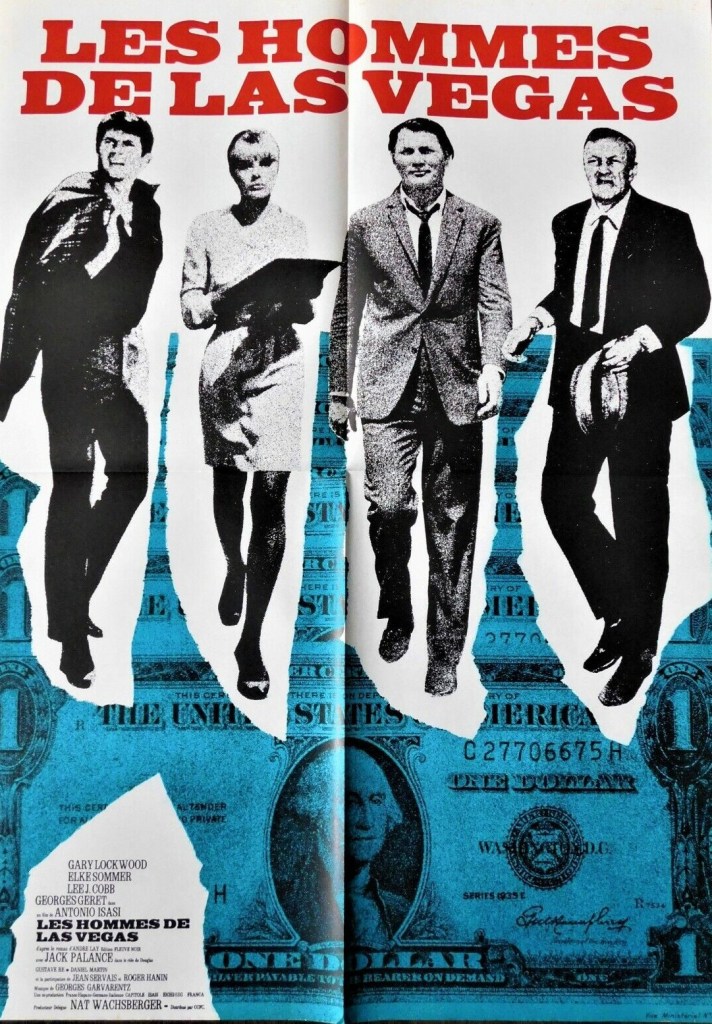

If you’re familiar with Spanish director Antonio Isasi-Isasmendi from They Came to Rob Las Vegas (1968) stick that to one side because this is way better. Screenplay by Giovanni Simonelli (Django Shoots First, 1966), Nat Wachsberger (Starcrash, 1978) and Luis Josep Comeron (They Came to Rob Las Vegas).

Great treat.