This is more like it. Classic Agatha Christie mystery told in classic fashion but devoid of either of her major sleuths, Hercule Poirot or Miss Marple, and set in the grander equivalent of the country house locale that had become something of a trademark. Here it’s the kind of castle perched atop a mountain, accessible only by cable car unless you have mountaineering skills, that you would need the combined services of Clint Eastwood and Richard Burton to affect a rescue, and as with Where Eagles Dare (1968) the conditions are distinctly wintry.

Ten strangers, including the two servants, have been invited to this retreat by the mysterious Mr Owen. They soon learn they are cut off, telephone lines down, cable car out of commission for a couple of days, nearest village a straight drop 15 miles down a perilous cliff.

All they have in common, as they discover via a taped message delivered by their host, is that they all got away with murder or at the very least a dubious death. There is a private eye on hand, former cop Blore (Stanley Holloway), but he’s lacking in the little grey cells that Poirot put to such clever use in such circumstances. So, like a troupe of actors let down by some stage entrepreneur, they have to get the show on the road themselves, a combined effort to solve the problem.

Not so much why they are gathered here, but why they keep on getting bumped off, and rather in the fashion of the titular song. The movie business wasn’t awash with serial killers though this decade would see nascent interest in this sub-genre, witness Psycho (1960) and The Boston Strangler (1968). But Ms Christie mysteries never really seemed to get going until the death toll had reached multiple figures.

The good element of this kind of movie with a large cast is that each character gets a moment in the sun, here that spotlight largely concerned with what crime they committed for which they were never truly punished. Pop singer Mike (played by pop singer Fabian) gets the ball rolling, explaining that his only punishment for killing someone while driving under the influence was a temporary withdrawal of his license.

And so it goes on, everyone wondering who will be next to be despatched and going from the initial conclusion that Owen is responsible and is hidden somewhere in the house to the obvious one that Owen is one of them. I have to confess I’m easily gulled by the murder mystery and I hadn’t reached that conclusion myself.

The movie’s not necessarily filled with that kind of twist – although there certainly are a good few, some people not as guilty as they might appear, not quite who they appear to be – more you glancing at the cast list and wondering, by dint of billing or box office pull, who will be next for the chop and unless the director has got the Hitchcock vibe it’s not going to be one of the leads.

So it’s a choice of Hugh Lombard (Hugh O’Brian), secretary Ann Clyde (Shirley Eaton), actress Ilona Bergen (Daliah Lavi), General Mandrake (Leo Genn), Judge Cannon (Wilfrid Hyde White), Dr Armstrong (Dennis Price) and the aforementioned Blore plus servants the Grohmanns (Marianne Hoppe and Mario Adorf). And this isn’t your standard serial killer either with a constant modus operandi that will eventually, through standard detection, trap him or her. Instead, variety is the key. Death by fatal injection, knife, poison, slashed rope.

As the numbers whittle down, and you even feel sorry for the actions of some, the actress, for example, whose husband committed suicide when she left him, the tension mounts. You won’t be on the edge of your seat because there are just too many characters involved for you to become overly concerned with their plight but it’s still has you on the hook. You do want to know whodunit and why and you can be sure Ms Christie, as was her wont, will have some clever final twist.

At least, unlike the later variations on the genre, nobody’s been bumped off because they are too fond of sex, and the violence itself is restrained, almost dignified, and there’s no sign of gender favoritism.

All in all, entertaining stuff, though since by now this kind of murder mystery, given we’ve been through various iterations of Poirot – Albert Finney, Peter Ustinov, Kenneth Branagh et al, not to mention numerous Miss Marples – a lot of this feels like cliché (though that’s a bit like a contemporary audience considering John Ford’s Stagecoach old hat, not realizing this was where many of those western tropes were invented or polished to a high level). And I had to say I had a sneaky hankering for some of the out of left field goings-on of The Alphabet Murders (1965).

Sad to see Hollywood not taking advantage of Daliah Lavi’s acting skills, under-estimated in my opinion after her terrific work in The Demon (1963) and The Whip and the Body (1963). But then this wasn’t Hollywood calling but our old friend producer Harry Alan Towers (Five Golden Dragons, 1967) who specialized in dropping a biggish American name into a B-list all-star-cast.

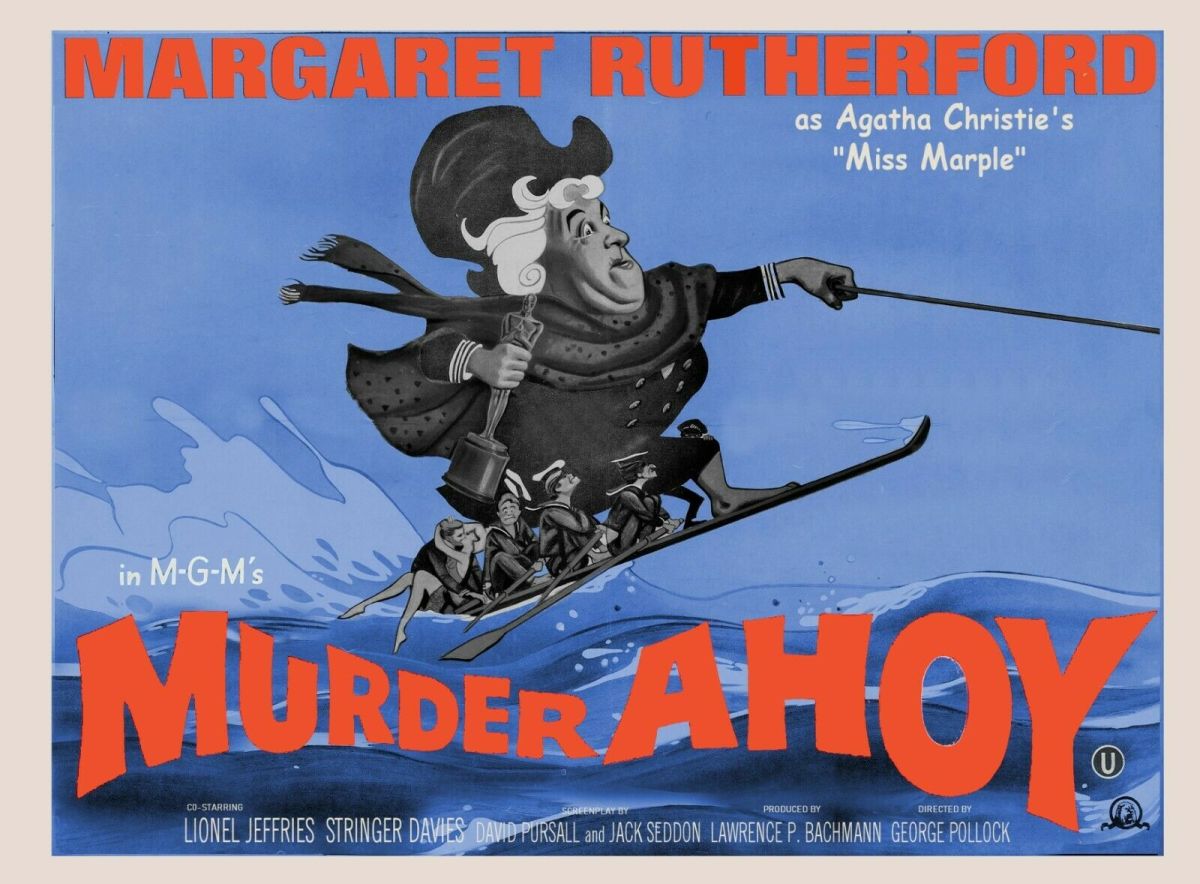

George Pollock, who helmed this decade’s four Miss Marple movies, enjoys keeping the mystery alive without resorting to a central know-it-all. Everyone cast does what they’re expected to do. Towers wrote the screenplay with his usual partner Peter Yeldham.

Worth considering alongside The Alphabet Murders, but stands up well on its own.

PREVIOUSLY REVIEWED IN THE BLOG: Hugh O’Brian in In Harm’s Way (1965), Texas: Africa Style (1967); Daliah Lavi in The Demon (1963), The Whip and the Body (1964), Lord Jim (1965), The High Commissioner (1968), Some Girls Do (1969).